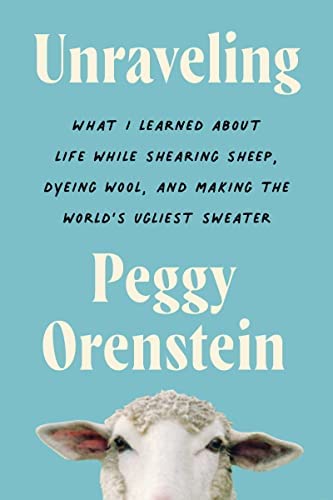

What I Learned About Life While Shearing Sheep, Dyeing Wool, and Making the World’s Ugliest Sweater

Sheep don’t look like they’d be slippery. It turns out, though, that they secrete a waxy substance called lanolin that weatherproofs their fleece—it’s the same stuff that’s in a lot of cosmetics, moisturizers, lip balms, and in the ointment nursing moms slather on cracked nipples. That means that when you try to hang on to one, it slides.

The ewe currently wedged belly-up against my legs is no exception: weighing in at around one hundred fifty pounds, she is wriggling like a greased-up toddler. A greased-up toddler with hooves. Did I mention that I’m holding a rapidly whirring electric clipper in my right hand? Its blades, which have no safety guard, are sharp enough to sever my finger, or, maybe worse, slice open a major artery on the animal. My arms are glistening with sweat from wrestling the sheep into position, my back already aches, and my Covid mask is stifling me.

Learning to shear sheep during the pandemic seemed like a bit of a lark—a way to tap into the romance and resilience of an earlier age; to connect with something enduring when life had become so precarious; to better understand, as a lifelong knitter, where my fiber came from; to get out of my house. Why the hell couldn’t I have stuck to sourdough? I think to myself as I look down at the giant ball of wool beneath me, raise my hand, grit my teeth, and prepare to plunge in.

This was certainly not where I imagined myself at the beginning of 2020. In early January I published a book on boys, masculinity, and sexuality, a follow-up to one I’d written about girls. I was on a national tour in a different city every day. The pace was exhausting, exhilarating. In the midst of it all, a friend back in California texted me an emoji, the one that looks like the face in Edvard Munch’s The Scream, along with the words “Covid-19!” I had no idea what she was referring to.

A couple of months later, things had changed.

What did you do when life came to a terrifying, screeching halt?

Me, I read the news incessantly, then avoided reading the news entirely: rinse and repeat for weeks, then months. I told dear friends, in soulful Zoom sessions, that I loved them (often while accidentally on mute), feeling simultaneously deeply connected and deeply disconnected. I made a list of Great Books for my 16-year-old daughter to read in case school never resumed (she balked). I gave it up and lifted all restrictions on her device use, the ones that were supposed to keep her from becoming a slave to the algorithm. I let her become a slave to the algorithm. I became a slave to the algorithm.

I confided my feelings all day, every day, to my mom. She never answered back. That’s because she’s been dead since 2016, a month shy of her eighty-sixth birthday. My mom was the one who’d first taught me to knit when I was around eleven. This would prove so ubiquitous among women I met while writing Unraveling that I began abbreviating it in my notes as SLFHM, she learned from her mom. No surprise there: craft has always been the province of women. Lessons on food or thread weave us together across the warp of time, the weft of space. For my mom and me, knitting bridged the generation gap, created reliably neutral ground where we could meet. When things were fraught between us—when I bristled at her, fairly or not, for being intrusive or narrow-minded or lacking all boundaries, when I resented that as a housewife of her era she could not be the guide to contemporary womanhood I needed—we could still bond over a trip to the yarn store, picking out our patterns, comparing colors, fondling the merch. She was a far better knitter than I, too, so although I dismissed her advice on nearly everything else, I would eagerly seek it out on a complicated sweater.

What I really wish for now is something impossible, in defiance of both physics’ and nature’s laws: not to talk to her as she was at the end of her life (or as she would be were she still alive today, at ninety)—physically frail, psychologically shaky—but to have a conversation with her at my age, and for me to be this age as well. Instead, I talk to her in my head, taking on both our roles, while knitting my thoughts, feelings, and fears into multicolored blankets and warm winter hats, just as she taught me.

In the pandemic’s early days, the rhythm of my hands, of the needles, as I sat on the couch watching TV (whether the news or anything but the news) was the only thing that calmed me, kept me still and patient. I couldn’t control what was happening in the world but I could control this: the tossing of the yarn, the tugging of the loop, the counting of the stitches, the accrual of the rows. Knitters are fond of pointing out that the repetitive action of needlework, like meditation or yoga, induces a relaxation response. It can lower blood pressure, heart rate, stress hormones. As a bonus, you get the primal joy of transforming raw material into something useful and, hopefully, beautiful.

No wonder during this time everyone who could—everyone safe and stable within a certain social class, all of us “worried well”—embraced old-timey, domestic crafts. We yearned for the tangible even as we flocked to the virtual, reverted to bygone comforts even as the present (and the future) were yanked from beneath us. We turned skills that were once—but are no longer—crucial to survival into ’grammable symbols of self-sufficiency and indomitability.

Maybe that’s why, scrolling by all those loaves of bread, tie-dyed sweat suits, and DIY knockoffs of Harry Styles’s cardigan, I began to think, Why stop there? This enforced pause in life could be my one chance to connect not only with my mom but with my ancestors, to act out my fantasies of going full-on Little House—setting aside the fact that Laura Ingalls, whom I also adored as a child, was, frankly, racist, and, in her post-frontier life, believed the New Deal was a socialist plot. I’d long dreamed, for reasons that, much as my editor would like me to, I can’t fully explain, of making a garment from scratch: shearing a sheep (though I did draw the line at raising one, or at least the city zoning laws drew that line for me), processing fleece, spinning and dyeing yarn, then knitting up the result.

Now, with an indefinitely empty calendar, nothing was stopping me from trying—at the very least, it would take my mind off the state of the world, give me something to do besides sit here and fret.

What I didn’t expect was all I’d discover about how clothing has shaped civilization, class, culture, power, or its pivotal role in our environmental future. I didn’t imagine how these ancient skills would deepen my awareness of women’s work or challenge my sense of place and home. I didn’t anticipate that this quirky little project would reflect the social justice reckonings of the moment, or that making yarn would help me untangle the knots of my own life. All I knew was that while everyone else was stress-baking and doomscrolling, I felt an inexplicable, unquenchable urge to confront a large animal while wielding a razor-sharp, juddering clipper; shear off its fleece; and figure out how to make it into a sweater.

From the book UNRAVELING: What I Learned About Life While Shearing Sheep, Dying Wool, and Making the World’s Ugliest Sweater by Peggy Orenstein. Copyright © 2023 by Peggy Orenstein Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

PEGGY ORENSTEIN is the New York Times bestselling author of Boys & Sex, Don’t Call Me Princess, Girls & Sex, Cinderella Ate My Daughter,Waiting for Daisy, Flux, and Schoolgirls. A frequent contributor to the New York Times, she has written for The Washington Post, The Atlantic, AFAR, the New Yorker, and other publications, and has contributed commentary to NPR’s All Things Considered and The PBS NewsHour. She lives in Northern California.

Question from the Editor: How do you unravel the ups and downs in life? Share with us in the comments!

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.