Steven Petrow Lost His Sister. He Worked Through His Grief by Telling Stories About Her—and Found Joy in the Process

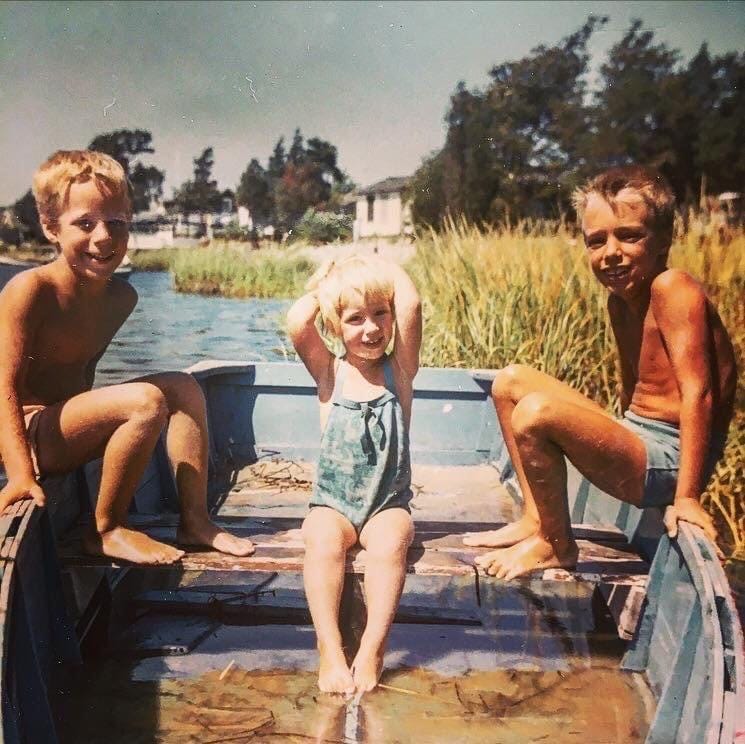

When my sister died last June, I found myself sinking in grief. At 61, Julie was the much-loved “baby” of our family, and her death from ovarian cancer felt unfathomable. My despair manifested itself as a pervasive numbness. Not knowing what else to do, I began to tell stories about her. While storytelling did not erase my grief, it began to melt the numbness, allowing me to feel again.

I started my storytelling at Julie’s memorial service, five days after her death. “She befriended everyone, but especially loved chatting up men in uniform, most of all firefighters,” I told the more than 400 assembled friends, colleagues, and family. “You might think this odd, since Julie was a lesbian, but that was my sister!” If she had been in that memorial chapel, I know exactly what she’d have said: “Steven, you’re so bad!” I loved when she told me that, which was often.

Ellen Steinberg, a good friend whose father died 15 years ago, told me why remembering and sharing our stories matters. “Talking about the deceased diffuses the pressure cooker of sadness that comes from people trying to hold it together and rise above the abyss the missing person has left behind. Talk about them. Share a story. Soon you’ll be laughing about a wonderful memory and quite literally bringing their spirit into the room.”

I took Ellen’s advice to heart and have continued to tell tales about Julie. In addition to helping me process my grief, public storytelling has eased the sense of isolation that I found separating me from others. Even more gratifying, talking and writing about my sister introduced her to a much larger group of friends—even strangers—which allowed me to forge a deeper connection with many of them. After reading one anecdote about Julie on my Facebook wall, a friend I didn’t know very well wrote, “The stories and experiences you’ve shared often leave me in tears, feeling as though I knew Julie personally, and always wishing that I could have met her and had conversations with her ... The stories that you’re sharing keep Julie present, which is a gift to all!”

I noticed that I’d usually be smiling, even laughing, when I talked about Julie. I found joy in the telling, a joy that resonated with others, a joy that helped to connect each of us. It occurred to me that the process was cyclical—the more stories I told the more I smiled, and the more I smiled the better I felt. Science bears that out, too, as research shows that the mere act of smiling can lower stress, boost the immune system, and, yes, improve our mood and make us more joyful.

As the verdant summer of 2023 turned to a fiery fall, I came to want a better understanding of the importance of storytelling—and the joy that it can give us. I turned to Jeremy Nobel, a physician and poet who recently wrote Project Unlonely: Navigate Loneliness and Reconnect with Others. “Storytelling is not only a common thread that binds us throughout our history,” he told me on the phone, “it is a personal way of revealing our authentic selves. Telling your story or listening to someone else’s story brings us together, it also better connects us to ourselves.”

“Why are stories so important to us?” he asked rhetorically, before telling me: “We take our personal experience and try to make sense of it, remember it, shape it, organize it, and put it out in the form of a story, then the world, the listeners … can make sense out of those stories and see us.” He added that stories “help us understand and empathize with others, can ease loneliness, and through shared narratives or themes foster a sense of belonging.”

I often choose to lighten the mood, for myself and others, by recounting Julie’s wicked sense of humor, usually at my expense. In the second month after she died, I posted:

“As a teen, more than anything I wanted to be a TV meteorologist. Our parents’ beach house on Long Island was especially subject to the wrath of the weather; even after it had been sold, I’d send frightening “winter storm warnings” to Julie and the family on our family’s text thread. (‘Oh my god, the house is going to be swept to sea!’). Last year I sent that exact text and within minutes saw a reply to the group from my funny sister: ‘Oh no, Steven’s having another ‘weather woody’!’ Apparently she—the ringleader—had noted this condition of mine a long time ago, and not been shy about sharing it with everyone but me. Even worse—it’s true!”

My public openness and vulnerability led to some surprising revelations from others, creating new bonds of understanding and empathy. My friend Donna recently revealed that her mother had died from esophageal cancer, and that they’d never discussed the possibility that she might not survive it. “This is my biggest regret. Thank you SO much for sharing about this special and heartbreaking journey,” she wrote me. I emailed back, thanking her for accompanying me.

Debra, whom I met nearly 40 years ago when we were volunteers at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, also reached out. “Right now I’m in a similar situation myself, preparing things so there aren’t decisions to be made at the last minute.” Confused, and mostly in disbelief, I wrote back, “Are you telling me that you’re dying?” “Yes,” came the answer. I thought about how Julie made space for many of us to have these difficult conversations, and how my re-telling of her stories made it permissible for others to break out of their own prison cells.

Jeff’s analysis reminded me of some wise words that Brené Brown wrote in Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. “[T]rue belonging only happens when we present our authentic, imperfect selves to the world….” I’d add this: True joy only happens when we present and share our authentic, imperfect selves to others.

As for the larger lesson, well, that’s pretty clear to me now: To be a good storyteller you don’t have to be funny. You don’t have to be weepy. You don’t even need a failsafe memory. It’s about the history and tales we conjure up—the stories that connect us as friends or family (whether by blood or by choice). These are the ties that bind us, that uplift us, that make us smile.

As it turns out, to talk about my sister I didn’t need any special storytelling talents—all I needed was Julie. And to be reminded, as I often am these days, of what she’d say: “Steven, you’re so bad!”

Washington Post columnist Steven Petrow has been thinking and writing about how to find joy in difficult times for many years now. His new book, The Joy You Make: Finding Life's Silver Linings in Good Times and Bad, will be published by The Open Field in September. This is a bonus chapter, not included in the book.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.