A Near-Death Experience Changed Sebastian Junger's Perspective on Life. This is What He Learned

It is a common truth that humans fear death. We avoid it and see it as a specter of loss and the unknown. This is understandable, says journalist and author Sebastian Junger. "The irony is, if you completely push death out of your scope of vision, you're at risk of failing to appreciate life."

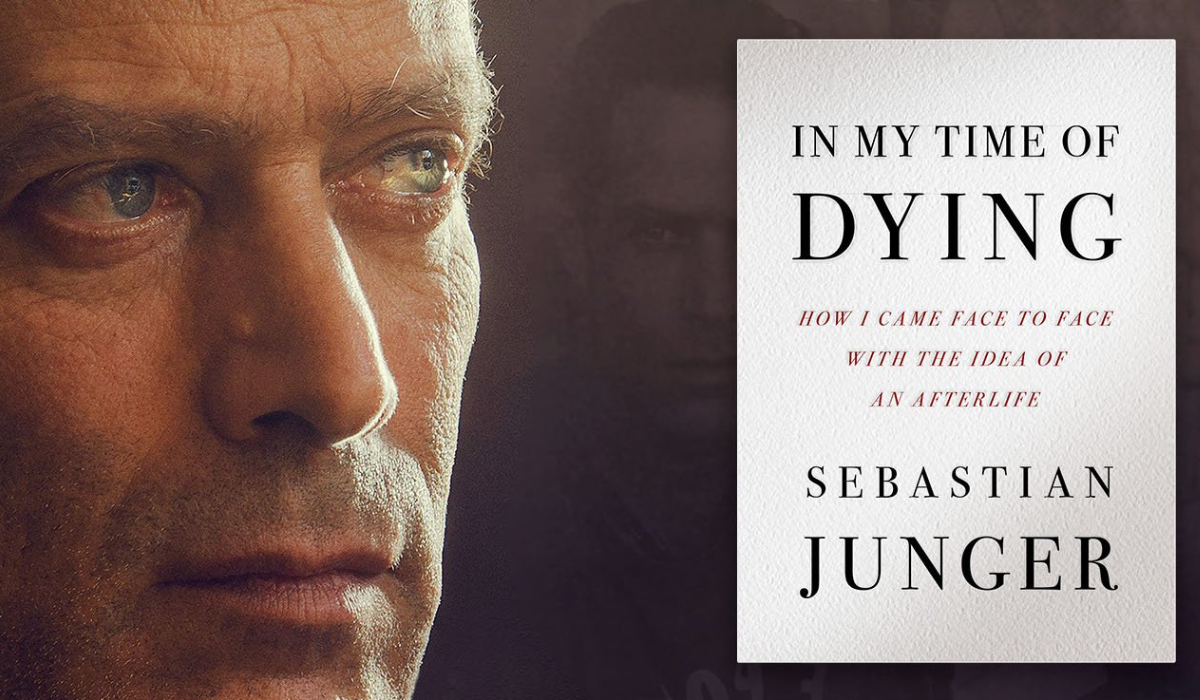

Death has had a significant presence in Junger's career, as he's spent years as a combat reporter on the front lines of wars. But it wasn't until 2020, on a quiet day at home, that he gained a new perspective. He became overcome with abdominal pain and was rushed to the ER, where he was losing blood and slipping away. He then saw a large black pit of darkness and his dead father. "He appeared when I needed him most," writes Junger in his new book In My Time of Dying, about the experience of seeing his father and nearly dying.

Junger's words on this event illuminate all that can and cannot be explained. But even more so, as he tells us, his near-death experience helped him even more appreciate the finiteness of our time on this earth. "People talk about time and existence very casually as if there's an infinite supply of it," he says "and there's not."

A CONVERSATION WITH SEBASTIAN JUNGER

You write everyone has a relationship with death, whether they want one or not. Will you tell us more about this?

People deliberately choose not to think about death because it's scary and intrusive, especially when we're young. I certainly was this way. It's understandable. But, that sort of denial, that deliberate non-relationship with death, becomes its own relationship. And that can have effects, as well.

You write about that yourself, how you took many risks when you were young.

There's a sort of school of thought in risk-taking where people who deliberately take risks are actually more anxious about death than most people. And they're taking risks to demonstrate that they have agency and they're not scared. And that actually is a function of anxiety disorder rather than competence and fearlessness. That was also certainly true for me.

You've spent a huge part of your life on the frontlines reporting on wars. You were in Afghanistan in the mid-90s. You were around catastrophes, and you lost people, including your dear friend, Tim, a fellow war reporter. How has risk-taking changed for you?

I was also a climber for tree companies, too, which was an obvious danger but one that allowed me to address my fears because I knew if I got killed, it would be only through a mistake. If I did everything right, I'd be fine. There was something about the amount of control that I had over the outcome that was enormously reassuring. I'm scared of heights, and I'm scared of dying. I was an anxiety-prone kid for a variety of reasons. And that allowed me to sort of control it. Likewise, going into combat.

I got out of combat reporting after Tim was killed. At the time, I was married to my first wife, and she was really close to Tim. She made this incredibly reasonable point to me. She said, 'Look, if you keep doing this kind of work, every time you go away and the phone rings, I'm going to think this is the call where I find out. Every time the phone rings, I'm going to jump.' And the call for Tim came on a landline to our apartment in New York. I got to thinking: I'm almost 50, and I don't want to keep putting my own interests ahead of everyone else's welfare.

You anchor your book in a near-death experience you had a few years ago. You had taken the morning off, and you were spending it with your wife, Barbara, when you got this extreme pain. Suddenly you're in the hospital, hemorrhaging, and at one point, you see a dark pit of blackness sucking you in. Then you saw your father, who is dead, right there by you. Some may say this cannot be medically explained. Now that you're on the other side of it, does it make sense to you?

I sort of went through other people's attempts to make sense of it. What happened to me is very common; it's called an NDE, a near-death experience, and the visions that I had are well known. They happen in societies around the world and certainly have happened forever. Our medical knowledge allows doctors to bring people who are dying, like I was, back into the world of living. So, we have a lot more of these stories of people who are on the threshold and what they remember. So, there are some medical explanations, but I found them not entirely sufficient. Some researchers believe that it's not proof but evidence of some kind of post-death existence. Then other people who are equally well informed say nonsense, this is neurochemicals, and it's blood oxygen, and it's a form of seizure. So, there are all kinds of straightforward medical explanations for the dying brain having visions.

The one thing that was never quite explained to my satisfaction is: Why do the dying see the dead or hallucinate the dead, and no one else does? If you give a roomful of people LSD, we know that 100 percent of them will hallucinate, but they won't all hallucinate the same thing. The dying hallucinate the dead, as I did, and no one else in the room can see them. Hospice nurses will tell you that it happens all the time. Neurochemistry can explain visions, but specifically, the content—and the content [in the case of the dying] is remarkably consistent.

You believe that your father showed up when you needed him most. Do you find solace in that?

I do, regardless of the explanation. That could have been entirely cooked up by my own dying brain, and it is still comforting. The relationship that we have with the dead continues in our minds until we die. At the very least, the relationship I had in my mind with my father changed. He was very sweet, but he was on the spectrum, and he was hard to reach emotionally as a father. So, I didn't sort of count on him throughout my life and as a child for that baseline emotional support. But then, there he was, and it really did sort of change things for me. Then there's a possibility that I have spent my life as an atheist, and my father was an atheist, but this all did make me think that possibly on a subatomic or quantum level, we don't really understand existence, life death, reality, consciousness, or universe and that there's some sort of post-death reality to the individual that we can't —and maybe never will be able to—make sense of and then that's what people keep bumping into around experiences like this.

It would be an easy question to ask what your near-death experience taught you about life. But you write that when we really drill down into this topic, we're talking about an appreciation for death. How can an appreciation for death open us to deeper meaning?

Sort of the psychological trick that humans tend to do is to push to the side a real awareness of death so they can engage in their busy lives. And our lives seem very important because it's all we know. Reality revolves around us, and it's impossible to conceive of a world without your own subjective viewpoint because it's all you've ever known. As humans evolved, with language and conscious thought, and the ability to see themselves in the future, the theory is that we developed a very fine ability to deny the reality of death in our everyday thinking because otherwise, it would be completely paralyzing. The irony is that if you completely push death out of your scope of vision, you're at risk of failing to appreciate life. It just seems like this sort of endless journey. But we think, Okay, well, another day went by, and I had to kill some time, so I went on TikTok. People talk about time and existence very casually as if there's an infinite supply of it, and there's not.

When you appreciate the reality of death, one of the things that happens is that it illuminates the truth about existence, which is that it happens moment by moment. Existence only happens in the current moment that you're in, and that keeps changing. That is what life is. There's no tangible past or future in life. There's only the present moment. So, if you think about life in those terms, what do you really want to be doing in that present moment? Because each moment is a a miracle. What I would say is that you want to be as present-minded as possible. This means, among other things, not being on your phone. I have a flip phone. All the stuff that you see people sort of quote killing time with is an insult to life right there. It's like we're throwing away food, knowing that eventually you're going to be starving.

This also doesn't mean we have to be in the lotus position in the woods. However, the distractions that this culture has come up with, from the industry corporations that have managed to monetize distractions and make trillions of dollars off them, cost us our peace of mind and our lives. It's as disgusting as what the cigarette companies did. So, to me, an awareness of death means that you will reevaluate everything that's taking your time and attention in your life and deciding which should go overboard and which shouldn't.

What helps you stay present when you find yourself getting scooped up in the chaos of it all?

We don't have a television. My girls, I have a seven-year-old and a four-year-old, are not allowed on any devices. I would say that the closest I come to transgressing in that way would be just a kind of exasperation, when I'm stuck in traffic, and I go, I can't believe this or I experience any other exasperation. Life is exasperating, and if you let that feeling take over, you're losing. It happens to me all the time, but I am aware of it now. And I have a new thing that I say to myself when I'm stuck in traffic, say on the Cross Bronx Expressway on a July afternoon. I just say to myself, Chill out, you're the traffic too. You are also someone else's traffic. This isn't a huge conspiracy to keep you from getting to the beach. When you do that, it actually calms you down.

No person in the world knows that this is not the last day of their life. None of us. None of us know. So, given that it could be, who do you want to be the last day of your life? What virtues do you want to represent on the last day of your life? I'm guessing you won't be on your phone that much. I'm guessing you will not harbor grudges. I'm guessing you'll be kind and loving to people and appreciative of everything. Weirdly, those are all pro-social behaviors that, if we all did them all the time, would save our society and our planet.

Sebastian Junger is a filmmaker, journalist, and the bestselling author of several books, including The Perfect Storm and Tribe, among others. As an award-winning journalist, a contributing editor to Vanity Fair and a special correspondent at ABC News, he has covered major international news stories around the world, and has received both a National Magazine Award and a Peabody Award. Learn more at sebastianjunger.com.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.