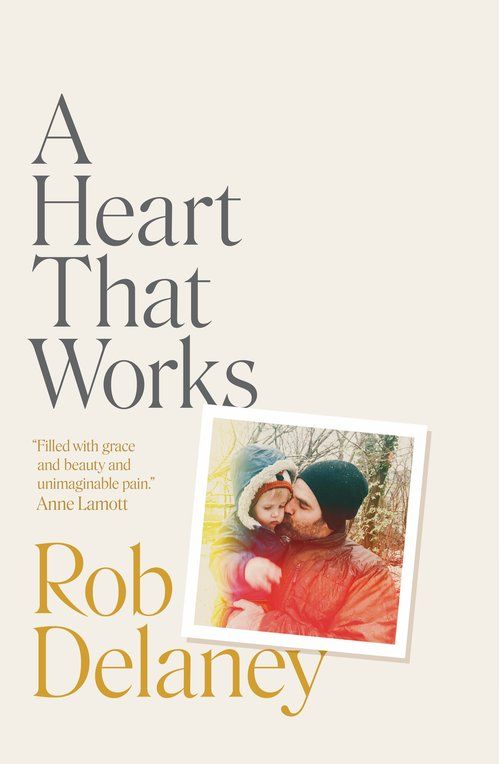

Rob Delaney's 2-Year-Old Son Died. Now the Comedian Is Sharing His Lessons on Grief, Love, and Life in His Stunning Memoir 'A Heart that Works'

“The best we can do is just hold and love each other—because life gets pretty rocky sometimes.”

So says Rob Delaney—a father, husband, writer, actor, and comedian. Delaney is talking with us about his new memoir, A Heart that Works, in which he chronicles the unimaginable: the death of his two-year-old son, Henry, to brain cancer.

A Heart that Works is beautiful and vital. It is immeasurably sad. But it is also clear about the deepest trenches of anger and confusion humans find themselves in because of grief. And in parts, it is even buoyant.

Delaney writes about a loss with which he and his wife and three other sons will forever be grappling—and one to which other bereaved parents can relate. But his words can serve everyone because they are reminders of how fragile, precious, and fleeting life is.

A Conversation with Rob Delaney

Rob, thank you for sharing your story. Near the beginning you write, “This is one thing grief does to me. It makes me want to make you understand.” What do you hope people take away from your book?

I want people to understand. And then the inevitable question is: What do I want them to understand? Of course, I struggle mightily with that answer. Because I still want to understand, too. I understand the fragility of life and the majesty of it, and the depth of the pain that is coming your way even if it hasn’t arrived yet. So I do hope that the book can help foster compassion between others because life is tough.

Too often we don't know how to talk about loss. We also wonder if we should mention a person who has passed. For those who may grapple with what to say, do you like when people ask about Henry?

Yeah, I really do. Because I'm always thinking about him. If you think you’re quote 'bringing him up', you're not because he's already up. He's already in my heart and I likely just thought about him and will be again in a few minutes. So it's not ambushing me or bringing up something that surprises me to have the image or the feeling of him enter my mind and heart. So I quite like to be asked about him.

There’s even curiosity. If you hear someone's two-year-old kid died, you probably want to know how. I'm perfectly okay with people asking how. I want to talk about it. Um, you know, I mean, like, worst case scenario, I might tell you something about some of the symptoms that a kid who cannot talk exhibits when they have a brain tumor. I know what that is, and most people don’t, so maybe I have an opportunity to tell you something that'll help save a life one day.

You mention in the book how pediatric cancers get less attention than adult cancers, much in part to capitalism and profit motives. What do you want readers to know about this subject?

That’s an interesting question. I didn't know that pediatric cancer was rare. It makes sense, but I've never consciously known that. Then it follows, of course, that it would be less lucrative for drug companies to do therapies if fewer people are getting it. So, a lot of cancer treatment for young people is retrofitted adult treatment that doesn't necessarily work. Their bodies are so different. Since I’m not an oncologist or a senator, there's not much I can do other than spread the word. And I am quite good at spreading the word. So I want people to know that there are people who know well that they’re focusing on adult cancer rather than kid cancer. And that for a bunch of those people, there's a profit motive behind that. What people want to do with that information is up to them. But I didn't enjoy learning that, and I don't imagine anybody else will either. That is one set of disturbing facts that I feel responsible to share with people.

What is the meaning behind your title, A Heart that Works?

The title is half of a lyric from a wonderful Juliana Hatfield song. The full quote is “a heart that works is a heart that hurts.” That is, very possibly, my whole life philosophy. Having been through this with Henry and my wife and his brothers, our hearts hurt. And in a way, thank goodness that they do, because it means: You're damn right we love that boy. I use the present tense because even though he's dead, he still gets a quarter of my parenting energy. His brothers—there’s three of them—get the other three-quarters.

It's sad. I’m sad right now. I'm laying down with my eyes closed as we talk about him. I'm not strutting around with vigor. This hurts. And that is okay. If I lay on this coach talking about him four-and-a-half years after he died about how honestly it hurts, I’m probably lying better and healthier groundwork for my future than if I just put on a brave face as if it wasn’t happening.

Through the book, there is a palpable feeling of deep love and deep sadness, and there is also gut-wrenching, raw anger that you don’t hold back. Will you talk about this?

I figured that would be best to do rather than to sort of prescribe what people might do or how they should feel. My thinking is if I show, to the best of my limited ability, somebody really feeling it, then maybe that might model a healthier way to do it. I figured the best thing I could do was to tell people what it really felt like.

It started out that I wanted to hurt people with the book. Now I'm realizing I think I might have written it because I love people.

Rob Delaney is a comedian, actor, writer, and the author of a previous memoir, Rob Delaney: Mother Wife Sister Human Warrior Falcon Yardstick Turban Cabbage. He is the BAFTA-winning co-creator and co-star of the critically acclaimed comedy Catastrophe. You can order his latest memoir A Heart that Works here.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.