Acclaimed Journalist Richard Engel on the Legacy of His Late Son Henry and the Honorable Role of Fatherhood

In August 2022, NBC News chief foreign correspondent Richard Engel and his wife Mary lost their six-year-old son Henry to Rett Syndrome, a rare neurological disease that impacts nearly every aspect of someone’s life, including the ability to walk and talk. Henry’s life was too short because of “a single devastating typo in his genetic code,” as Richard explained on TODAY.

There is no cure for Rett Syndrome, but there is promising research. The Sunday Paper called Richard to discuss Henry’s life and legacy. Doctors and scientists at Duncan Neurological Research Center in Houston, Texas, who worked with Henry, are using his genes to understand this rare disease better.

In our conversation, Richard, also father to four-year-old Theo, talks about what he and Mary wish for other families fighting rare diseases, the need for more awareness around extreme disabilities, and how Henry’s tenacity continues to bring him beauty and hope.

A CONVERSATION WITH RICHARD ENGEL

There are doctors and scientists dedicated to researching Rett Syndrome, some of whom at Duncan NRI are concentrating on Henry's unique genetic mutation. Please tell us about this research's possibility and how it carries Henry's legacy.

What they're doing specifically with Henry's genes at Duncan is amazing. Henry's mutation was one of a kind. They've never seen one like it, making it valuable and giving this research opportunities. Dr. Huda Zoghbi, an incredibly prominent neurologist, had dedicated a team of scientists to researching Henry's genes, which are alive in genetically mutated mice. So today, mice carrying Henry's actual mutation are being experimented on. There are also frozen samples so future generations can continue this research if we still need to get there.

They are making promising progress. This could help other children who have other similarly rare genetic diseases. There's also lots of other research happening in different laboratories that are making strides. It's difficult to see that for Mary and me because it's too late for Henry, but we wish for nothing more if this can help another child and another family.

There seems to be a lack of knowledge about many disorders and diseases, particularly those that impact children. Can we better broaden our awareness around illnesses and disabilities that don't get much public attention?

I think we can. While we talk about inclusion and we talk about awareness for people with disabilities, it's often not about people who are at the extreme end of the disability scale. This includes people who are not going out as much, who stay home more, and who have a condition that is more difficult to look at and causes people to feel uncomfortable. So there is little visibility on the extreme end of the disability scale. There are ramps for people in wheelchairs and Braille on elevators, but people who have severe neurological disorders, like Rett, are still underrepresented. You don't see them very much.

We'd love to hear more about Henry. Mary used the word "tenacity" to describe him. Will you share a story about him?

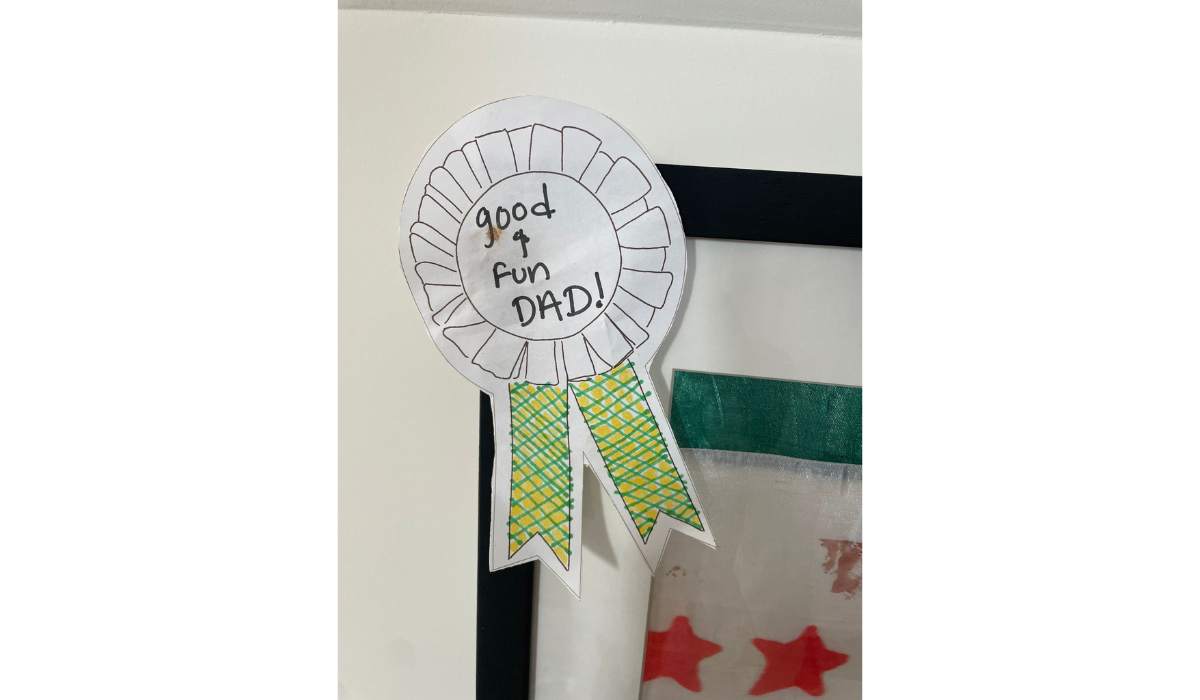

Absolutely. Since it's Father's Day and you asked about tenacity, I'll tell you this story: I keep a card that I got from Henry on the wall in my office. It is a ribbon—a cut-out from a piece of paper. It's one of my treasured possessions. Many dads get Father's Day cards from their sons; initially, mom may help. That's what this was. But the amount of work and help required to create this card was unlike any other.

Henry had such a severe disorder he couldn't walk or speak. He had limited control over his limbs. He communicated by trying to look at other cards. We would hold up a 'yes' and a 'no' card so he could make any kind of motion toward one card. This was a profound step in communication. Then we had a flipbook, which Mary had made some of the cards for. This included translucent pieces of plastic with pictures around the edges. We would hold these in front of our faces to make eye contact with Henry and see what photos he was looking at. Then the next step was a computer tablet that uses eye gaze technology to track your eye's movement to see if you've settled on any one word or concept. This was a struggle for Henry because he couldn't always control his body or eyes. Mary used all of these things with Henry over time. He was about four-years-old at the time, so she couldn't sit there for hours and hours. She had to find the right moments. So she sat with Henry, using all these different communications tools so he could pick all the colors and shapes and create this card.

I'm looking at the card right now. It says, 'Good Fun, Dad.' I have it stuck to my wall. That's tenacity. To have the patience to sit there and do this kind of thing all day. To try to express a minor desire when your body's not cooperating. Where there are thoughts, ideas, and emotions that want to get out, but you can't get them out. That takes a lot of tenacity and patience.

And how is Theo?

Theo is doing great. He's athletic. He loves to roughhouse. He wakes up in the morning, comes into bed, 'Let's rough house!' We play a lot of imagination games. He's wonderful.

Thank you, Richard. On this Father's Day, what does the role of being a father mean to you?

You're there to help your kids get through this world. This world is not an easy place to navigate. I'm still learning, But at least I can help show them the way and to learn from some of my mistakes. I know there are certain things they will have to learn for themselves. But if I can give them good direction, a good life, good protection when they need it, and inspiration, I'll look back as a father and think I've done a pretty good job.

Richard Engel is NBC News' Chief Foreign Correspondent, an author, and a father. He's been covering global wars, revolutions, and political transitions for more than two decades.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.