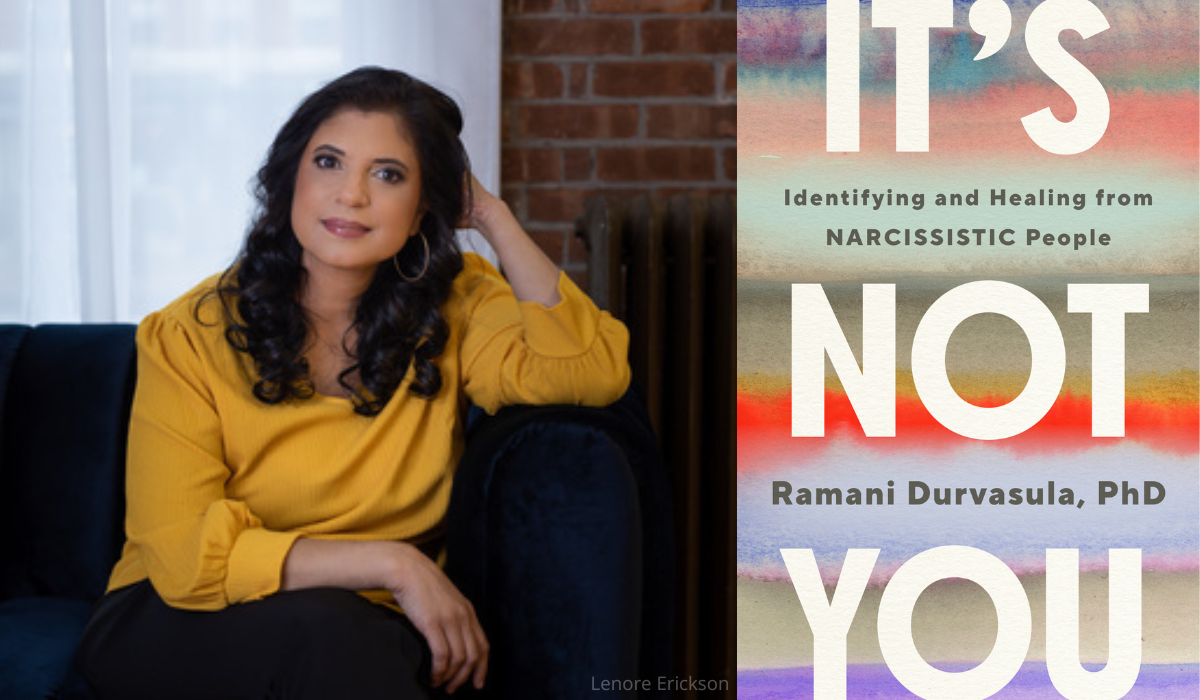

Dealing With a Narcissist? Ramani Durvasula’s New Book From The Open Field is the Ultimate Guide to Healing and Moving On

Please enjoy this exclusive extended excerpt from Dr. Ramani Durvasula’s new book, It's Not You: Identifying and Healing from Narcissistic People. Then grab your copy and read along with us for a Special New Book Club Edition of Conversations Above the Noise with Maria and Dr. Ramani! PLUS—Don’t miss 15% off your purchase of It’s Not You when you RSVP today!

How Did We Get Here?

Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim.

Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.

ELIE WIESEL

9:00 a.m.

Carolina has two children and was betrayed and cheated on by her husband several times during their twenty-year marriage, including with friends and neighbors. After he denied it repeatedly, and then after enduring his rage for her “paranoid accusations,” she was told the affairs were her fault for making him feel like he wasn’t important. She would minimize her career so he felt “safe.” She struggles with missing what she believed was the beautiful lifeand family they created, with feeling not enough, believing that maybe she was misunderstanding him and the situation, knowing it was breaking her heart every time he criticized her and betrayed her trust. Carolina didn’t understand it; she has parents who had been happily married for forty-five years until her father died. She believed in family and now with the impending divorce, she felt she had failed. She was also experiencing regular panic attacks and debilitating anxiety, and sometimes ruminated about a reconciliation.

10:30 a.m.

Nataliya has been married for fifty years to a man who told her that she was being “ridiculous” for expecting so much of him when she had cancer. He said it was “disruptive” and throwing him off because now he was supposed to feel sad for her and up-end his busy schedule to pick her up from chemotherapy appointments. She found it difficult to walk after developing neuropathy following years of cancer treatment, and he would shame her and call her “the empress” for asking to be dropped off in front of a restaurant instead of walking five blocks on a cold night. However, they have adult children and grandchildren, and a life filled with travel and family time. Nataliya doesn’t want to be the one responsible for messing up a lifestyle that everyone is enjoying, and she acknowledges that on more than a few days, she enjoys her husband’s company—they still have a decent sex life and a shared history. Despite her having both medical and law degrees, he treats her like a personal assistant. She has struggled with ongoing health conditions, self-blame, and shame, and has become socially isolated from everyone except her close family.

1:00 p.m.

Rafael’s father has compared him unfavorably to his brother since childhood, and he works constantly with the fantasy that once he makes enough money, he will get noticed. His father often perceived him as weak, would take some glee in telling him about his brother’s latest successes (Rafael had long since distanced from his brother), and had been emotionally abusive toward his wife, Rafael’s mother. This resulted in a tremendous psychological toll on her, which Rafael believed resulted in her premature death. Rafael knows that his grandfather did the same thing to his father—it was just how it was for them culturally—and he also wanted to make allowances for the racial biases and limitations his father and grandfather faced throughout their lives. Rafael has not been able to sustain successful intimate relationships and keeps telling himself, “If I can just show Dad my success, then I will be okay and ready to start the rest of my life.” Rafael works around the clock, relies on a mix of drugs and remedies to sleep and to get going, rarely socializes, and craves socialcontact, but says it feels “indulgent” to go on vacation or hang out with people when there is so much work to do.

LET’S CALL THIS a hypothetical day in my office. Over the years, having listened to enough of these stories, it became clear that in just about every case like Rafael’s, the parent would remain invalidating, and with folks like Carolina and Nataliya, their partners would continue to blame them. But it wouldn’t have been helpful for me to tell Rafael, Carolina, and Nataliya up front that the people in their lives would likely continue their harmful behavior. Instead, our work became about teaching them what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable behavior and what healthy relationships are about, while creating a safe space for them to explore their feelings, these relationships, and their true selves. We had to make sense of the confusion and explore why they were blaming themselves for something they didn’t do or feeling guilty when they were doing nothing wrong. As a therapist, I would have found it easier to just focus treatment only on the anxiety, health issues, depression, confusion, dissatisfaction, frustration, helplessness, social isolation, and obsessive work tendencies and not include the context. That’s what we are taught to do: focus on the maladaptive patterns of the person in the office instead of what’s going on around them.

But there was something else happening. Week after week, my clients’ panic and sadness ebbed and flowed alongside the patterns and behavior within their relationships. It became clear that the relationships were the horse and the anxiety that got them into therapy was the cart. I was struck by the similarities in so many clients’ stories, yet these clients were very different people with different histories. But where they didn’t vary was that all of them felt they were to blame for their situations—they doubted themselves, ruminated, felt ashamed, were psychologically isolated, confused, and helpless. Increasingly, they censored themselves in these relationships and became progressively more numb and restrained to avoid the criticism, contempt, or anger from these challenging people in their lives. They were trying to change themselves with the hope that this would change this person and relationship.

There was another significant similarity: the behaviors that were happening in their relationships. Regardless of whether it was a spouse, partner, parent, other family member, adult child, friend, colleague, boss—my clients consistently shared stories of being invalidated or shamed for having a need or for expressing or being themselves. Their experiences, perceptions, and reality itself were regularly challenged. They were blamed for the problematic behavior of these people in their lives. They felt lost and isolated.

Yet at the same time, all of them shared that it wasn’t bad all the time. There was sometimes laughter, good sex, enjoyable experiences, dinners, shared interests and histories, even love. In fact, just when things seemed as though they were becoming untenable, there would be a decent day, just enough to reseed the self-doubt. I gave my clients what had helped me in my own healing—validation and education. Focusing on their anxiety without educating them about the patterns within these relationships was like fixing engine problems by putting air in the tires. And those engine problems always seemed to track back to the same place: narcissistic relationships.

There is a proverb that says Until the story of the hunt is told by the lion, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter. The person who holds the narrative holds the power. Until now, we have only told the story of the hunter. Books about narcissism tend to talk about narcissists. We are deeply curious about these charming people who seem to get away with so much bad and hurtful behavior with so few consequences. We are compelled to understand why they are ostensibly so successful and why they do what they do. As much as we may not like narcissism, we glorify people with these personality styles—they are our leaders, heroes, entertainers, and celebrities. Unfortunately, they are also our parents, partners, friends, siblings, children, bosses, and neighbors.

But what about the lion? What about the person whom the hunter goes after or harms?

Much of what’s written about narcissism tends to forget the more important part of the story: What happens to the people who are in the wake of the narcissist? How are people affected by folks with narcissistic personalities and the behaviors? When people are hurt, there is a preoccupation with understanding the “why”— as if this could somehow ease their pain (it doesn’t). We become so curious about the hunter in an almost obsessive zeal to understand why they do what they do. Why would someone lack empathy or gaslight or manipulate or lie so skillfully or rage so suddenly? But in focusing on why people with narcissistic personalities do what they do, we lose sight of what happens to the people who fall in love with, have children with, are raised by, are related to, work for, work with, get divorced from, share apartments with, become friends with, and raise narcissists. What happens to them?

The short answer: it’s not good.

This is an uncomfortable conversation. You don’t want to cast aspersions on the people you love, admire, respect, and care about. It’s easier to take responsibility for your difficult relationships yourself, or write it off to the ebbs and flows of life, rather than accept that you are facing predictable, unchangeable, and harmful patterns from someone you love or respect. As a psychologist who has worked with hundreds of survivors of narcissistic abuse, who maintains a program for thousands of more survivors, and who has written books and created thousands of hours of content on this topic, I grapple with whether it is even aworthwhilee conversation to focus on narcissism, because the issue is really the harm the narcissistic person’s behavior causes you.

Can we separate the personality from the behavior if the personality is not likely to change? Does it matter if their harmful behavior is intentional or not? Can you heal without understanding narcissism? And most importantly, can you heal from these relationships? This book will explore those complex questions.

There is pushback from people who ask me, “How do you know the partner/parent/boss/friend is narcissistic?” Fair question. When I am working with a client in therapy, I have typically not met the other people in their lives, but I am getting a detailed history, often reading emails and text messages that have been sent to them by the antagonistic person and witnessing the impact on my client. I use the term antagonistic relational stress to describe what happens to survivors of these relationships, and I prefer to characterize the behavior of the psychologically harmful person in my clients’ lives as antagonistic, which is a broader and less stigmatized term than narcissistic. This is the term I use when teaching other professionals about these patterns, because it captures the breadth of antagonistic behaviors and tactics that we observe in narcissism—manipulation, attention-seeking, exploitativeness, hostility, arrogance—but also in other antagonistic personality styles, such as psychopathy, and positions it as a unique stress that antagonistic relationships evoke. But the narcissistic cat is out of the bag, and the term narcissistic abuse is familiar to most of you, though I will also use the term antagonistic throughout this book to capture the full breadth of these patterns.

YOU DON’T GET into this work unless it is personal, and yes, for me, it’s personal. I have encountered narcissism-induced invalidation, rage, betrayal, dismissiveness, manipulation, and gaslighting in my family relationships, intimate relationships, workplace relationships, and friendships. It hit me in the gut as I listened to the pain being shared by the clients I was working with, then going into my own therapy and sharing my own pain, and slowly realizing it was my story, too. Narcissistic abuse has changed the course of my career and my life. I was so gaslighted, I thought up was down, that I was to blame, that my expectations for people were not realistic, and that I was not worthy of being seen, heard, or noticed. It was foundational for me, and that fear of grasping the purple dress morphed into feeling unworthy of success, love, or happiness as an adult. There was no penny-drop moment, no singular defining relationship. Narcissistic abuse happened in many different relationships and ways in my life, so I believed this must be me, it can’t be all of these other situations in my life. I never learned about narcissistic abuse in graduate school; I didn’t think that this confusing and abusive behavior was a thing until I finally saw it clearly. I spent years grieving and then wishing I could get back the years I wasted in rumination and regret. I felt guilty and disloyal for viewing family members and people I loved as narcissistic. I slowly set boundaries, radically accepted that none of this behavior would change, stopped trying to change the antagonistic people in my life, and disengaged from them and their behavior. I lost relationships that once mattered to me and faced criticism for violating ancient cultural norms about family loyalty and current norms about needing to figure out a way to get along with people who have sharp elbows. I now realize that if you spend enough time with sharp elbows, you will end up bleeding to death.

A little over twenty years ago, I was supervising research assistants who were reporting back about certain patients in outpatient clinics wreaking havoc on nurses, physicians, and everyone else who worked there through their entitled, dysregulated, contemptuous, and arrogant behavior. That observation led me to start a research program looking at personality, particularly narcissism and antagonism, and how it affects health.

Simultaneously, I have had the privilege of hearing the stories of thousands of people who have endured these relationships. Unfortunately, I kept hearing that many times the partners, family members, friends, colleagues, and even therapists were blaming the person experiencing the abusive behavior for being too sensitive, not trying harder, being too anxious, not being more forgiving, staying, leaving, being judged as harsh for using the term narcissist, and not communicating more clearly. I have read descriptions of therapist-training programs that pushed back on clients who believed their families or relationships were toxic, or believed clients who came into therapy to talk about manipulative relationships were simply whining. There were countless books and articles written about narcissistic personalities and how to do therapy with narcissistic people. There were virtually none that addressed what happened to people in these relationships or how to do therapy with people who were in relationships with narcissistic folks, even though everyone in the field of mental health knew that these were unhealthy relationships. Once I unclenched my fists, I turned my anger into a focus on education, not only for clients and survivors of narcissistic abuse but also for clinical professionals.

The clients I have worked with have gone through divorces that spanned years; been doubted by the leadership in their company when they made documented claims of harassment and abuse and watched the workplace perpetrator be moved to a new post in a different location; been cut off by their families when they set a boundary; had grandchildren withheld as punishment; watched elderly parents be financially abused by narcissistic siblings; survived invalidating childhoods just to have to survive invalidating adulthoods; had narcissistic friends start online smear campaigns when they didn’t get their way; and had narcissistic parents manipulate them from their deathbeds. I have worked in organizations where gaslighting was the preferred mode of communication, and I witnessed the most toxic people be enabled by the systems they worked in, to the detriment of the best and brightest in those places. Personally, there are roads and neighborhoods in Los Angeles I still avoid because I don’t have the bandwidth to deal with the memories. I have experienced threats to my safety and felt compelled to leave jobs, and I have watched family be more concerned with protecting a family member’s reputation than in offering solace to someone who is suffering. It takes me a long time to build trust with new people.

The only thing you need to understand about narcissism is that in almost all cases this personality pattern was there before you came into the narcissistic person’s life and it will be there after you leave. These relationships change you, but out of that shift comes growth, a new perspective, and greater interpersonal discernment. Recognizing and coming out of these relationships can be a wake-up call to excavate your authentic self, dust it off, and take it into the world. The traditional therapeutic goal of teaching clients to understand their role and responsibilities in a relationship and to learn to think differently about situations that aren’t working doesn’t consider that the deck is stacked when it comes to managing these situations with a narcissistic person. Short of deluding yourself about the relationship, how differently can you think about someone who is manipulating you and negating your existence as a person? Instead of learning to think differently about the person, it’s time we started learning about what constitutes unacceptable and toxic behavior.

I hope that this book shines a light on a simple premise that narcissistic patterns and behaviors really don’t change and you are not to blame for another person’s invalidating behavior. I want you to land on a simple yet profound truth:

It’s not you.

I have heard from people around the world that simply receiving a framework for narcissism and what these relationships do to them marked the first time they felt normal in years. This isn’t about calling out narcissistic people but rather about identifying unhealthy relationship behavior and patterns. To be given permission to disengage. To learn that multiple things (good and bad) can be true in a relationship. To learn that understanding narcissism doesn’t mean you have to leave or end contact with people you have complicated relationships with, but instead that you can interact with them differently. To understand that it is a basic human right to be seen and to have your own and separate identity, needs, wants, and aspirations expressed and recognized. To become aware that instead of thinking differently about yourself, it’s time to start thinking differently about the behavior of someone whom you love or respect but who is also harming you. To finally be told, clearly and definitively, that you were never going to be able to change another person’s behavior. All of this was like turning the house lights on and the gaslights off.

This is a book for you, the survivors of invalidating relationships with narcissistic people. This is not a book about how they tick but rather how you heal. There will be a brief overview about narcissism to ensure we are all on the same page, but the rest of it is for and about you. The story of the hunt told by the lion, as it were. It will review the effect of narcissistic people’s behavior on you and how you can move forward, recover, and heal from a place of grace, wisdom, compassion, and strength. This is a book written from both my head and my heart.

Often when you get out of a narcissistic relationship or disengage from one, you think of it is as an end, but in fact the healing and all that follows is where everything begins. This is the beginning of your story, of stepping out of the invalidating shadow and finally allowing yourself to be you.

No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.