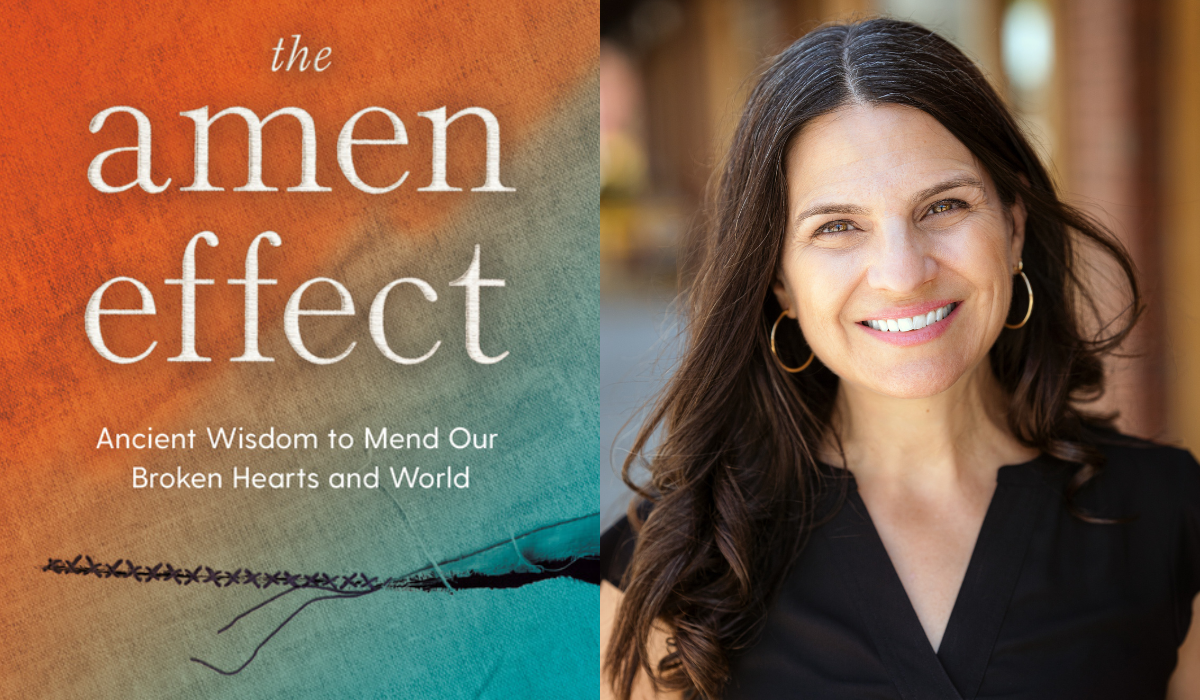

From Her New Book, Rabbi Sharon Brous On the Power of Difficult Conversations to Heal Our Broken Hearts

It’s the day after the 2015 Jerusalem Pride Parade. A religious zealot has brutally stabbed Shira Banki, a sixteen-year-old LGBTQ ally. She lies in the hospital in critical condition. We don’t know it at the time, but Shira will succumb to her wounds a few days later. The tragedy of her death, which shook the nation, would become a devastating reminder of life’s fragility and the attendant imperative to use every day to fight for a more just and loving world.

One of my congregants, Hannah, was standing only about ten feet away when it happened. Hannah grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family, and her own coming out was a painful journey of courage and resilience. She was in Israel for a relative’s bat mitzvah and had been at the parade with her wife, Kathleen. Now Hannah walks into Shabbat dinner, still reeling from the violence she had witnessed the day before.

By chance, seated across the table from Hannah is Asher, a twenty-year-old friend of the family. Hannah had heard that Asher had been radicalized during the past few years. He’s part of a movement of extremists with competing rap sheets for acts of vandalism and violence against both “lefties” and their Palestinian neighbors, a crew that’s more outraged by the Pride Parade—in their view, a threat to the sanctity of the Holy City—than even the stabbing of a child. At first, Hannah is sick to even sit in such close proximity to this person. But as the meal progresses, she finds herself growing increasingly curious. Who is he, really? How could a person hold these views? Does he really believe them? Can he even see her there, right across the table?

Authentic human connection:

• is a spiritual and biological necessity

• is the key to belonging and the antidote to loneliness

• can be the deepest expression of faith, honoring the image of God

• gives our lives purpose

• helps us approach moments of joy and pain authentically

• helps both the wounded and the healers

• won’t save us, but matters profoundly nonetheless

But what happens when encountering the other is more than inconvenient, uncomfortable, or even destabilizing, but actually treacherous, even dangerous? What happens when another person’s presence in the sacred circle—or at the dinner table—not only repels us, but renders us unsafe? When is it right to withdraw from the shared space, or to protect the space from those who would do harm there?

The dynamic between Hannah and Asher was fever-pitched because of the timing, right in the aftermath of a violent attack. But so many of us have experienced the breakage of our time: friends who reject science, parents who embrace conspiracy theories, colleagues whose hearts have become hardened to the point that they’re no longer recognizable. Marriages strained. Families shattered. Friendships ended. In our time, we increasingly perceive one another’s positions not only as incomprehensible, but morally repugnant. The last thing we want to do is find our way to one another. In the mid-2000s, I wrote a short piece to my community insisting that our hearts must be capacious enough to hold not only Jewish suffering but also Palestinian. That the quest for a just society needed to include justice not only for our own people, but also for Palestinian people, who also deserve to live with dignity. The piece, which went out to a private email list of community members, was somehow seen by an old teacher of mine, now living in Israel, and it tore him up. In response, he wrote a scathing public critique: I was emblematic of an army of “dysfunctional” “universalists,” “disloyal” to our own people and history, a greater threat to our people than even our external enemies. I found his response shocking and disturbing, but one line of his missive simply made no sense to me at all. He argued that my compassion toward Palestinians taught him that my world and his “simply no longer inhabit overlapping universes.”

It took me nearly a decade to understand what he meant. Hannah and Asher, my congregants and their family members and former friends, this former teacher and I are not only apart on the issues, we’re worlds apart. Those who hold opposing political views are not just ideological foes. Increasingly, we see one another as existential threats. And once two people no longer inhabit overlapping universes, well, it’s not hard to imagine devaluing their humanity altogether.

How did we get here? Two countervailing forces have driven this crisis: social alienation—the disintegration of collective bonds, leading to the fragmentation of our society—and tribalization—harsh lines of social division that carve up the population into exclusive, homogenous, often oppositional groups. These forces are not unique to our time, but both are exacerbated by digital technology and social media. These tools of connection have, paradoxically, led to what Sherry Turkle terms an erosion of empathy, dragging dangerous, malignant forces from the margins to the mainstream. The convergence of these trends is leading us right to the edge of the abyss.

SOCIAL ALIENATION

A lonely person can become a sick person, in body and spirit. Similarly, a society of lonely, atomized, socially disconnected people will become a sick society, one susceptible to extremist ideologies and powerless to resist dangerous social and political upheaval.

For decades, we’ve witnessed a mushrooming of social alienation and disconnectedness, and we seem to have reached a crisis point in the past few years. Today, nearly a third of Americans report no interactions with their neighbors, and an astonishing 20 percent of Americans report that they have no close personal relationships at all, a number that has more than doubled in the past decade. Imagine: No neighbor to knock on the door just to check in when you’re ill. No one to process the fear, confusion, and displacement of these uncertain times. No one to help us hold our personal or collective grief.

This level of isolation and disconnectedness is not only concerning, it’s dangerous. Political philosopher Hannah Arendt warned half a century ago that widespread social alienation is a precondition for the flourishing of violent political extremism:

Terror can rule absolutely only over men who are isolated against each other . . . therefore, one of the primary concerns of all tyrannical governments is to bring this isolation about. Isolation may be the beginning of terror; it certainly is its most fertile ground; it always is its result.

For Arendt, isolation is impotence. The more limited our meaningful contact with one another, the more we lack the ability to act together toward the common good, let alone to respond effectively to the grave dangers we face. Alone and apart, we are powerless.

TRIBALIZATION

But alienation is only one ingredient in the complex social puzzle of our time. Remember: human beings, from birth, are hardwired for connection. But we are also, by nature, tribal beings, meaning we instinctively look to build and reinforce relationships with people we perceive to be like us, whether that means they look like us, talk like us, pray like us, or vote

like us. Tribal attachments can be meaningful and beneficial; a sense of belonging can be a source of strength and purpose. The tribal mindset leads us to fight mightily for those we identify as part of what my friend, Sikh American lawyer, author, and activist Valarie Kaur, calls “our circle of care and concern.” But there is a dangerous side to the tribal instinct. Ironically, the stronger the bonds of connection to those in our group, the weaker the bonds are to those outside the group, leaving us indifferent or even hostile toward those who are not in our tribe. This is the cost to self-segregating in tribal bubbles, whether organized around race, religion, ethnicity, or ideology.

Curiosity is the birthplace of compassion, but the greater the psychological distance between us and the other, the less curious we are about one another. When we don’t wonder what the other is thinking or feeling, or where the pain comes from, when we don’t interrogate our presuppositions, our hearts close to one another. This leaves us less understanding of other perspectives, more entrenched in our own dogmas and narratives, and more susceptible to dangerous, fringe views. A society devoid of empathy is at great risk of falling into patterns of dehumanization that have, throughout history, led to the most extreme acts of violence, including genocide.

Extremist movements are already testing the very limits of our democracies. And all indicators are that this will only worsen in the days ahead, unless we find the appetite for a dramatic course correction. It is precisely now, when our instinct is to recoil from one another, that the need for an ethos of sensitive, sincere encounter is vital and urgent, not only for us as individuals, families, and communities, but for our society.

I return us to Hannah and Asher, seated across from one another, one having just witnessed up close a murderous hate crime, and the other, an extremist whose sympathies lie more with the perpetrator than the victim. Hannah doesn’t speak. But she stays at the table for hours, fighting to hold curiosity over antipathy. “I keep staring at him, surreptitiously,” she tells me later. “I’m trying to bore a hole into his head to get some clarity on what makes him tick. What makes him hate?” As a gay Jew from the Orthodox world, she explains, she’s had to live with contradictions her whole life—so she has a fairly high threshold for discomfort.

Even still, Hannah is burning with the desire to do something, to say something. Finally, she stands up, not to speak to Asher directly, but to address the room. She turns to the bat mitzvah girl. “You live in a time and place of great brokenness,” she says, choosing each word carefully. “Every day there are more and more stories happening right here in this country of hate crimes, retaliations, racism, sexism, senseless hatred. These are real struggles, real challenges . . . Keep your eyes and ears and, most of all, your heart open as you go through life. And don’t ever lose your voice.”

A week later, Asher reaches out to Hannah’s family. The bat mitzvah has turned him upside down. He’s really struggling. He spent shabbat with a lesbian! He tells them that he keeps asking himself, Would I have wanted anything to happen to Hannah? And he realizes: absolutely not.

And that’s that. Something has changed in him. Suddenly, he sees that rhetoric has consequences, that there’s no justification for hatred, that violence is not the answer. Three years later, when Asher shows up at the Pride Parade in Jerusalem, it’s not to protest, but to join the march. The following year, he’s back again, this time with his baby in a stroller and a rainbow sign: “Hate kills! Love is the only answer.” Now he has fully renounced the violence and zealotry of his early years. He’s a peace activist, an LGBTQ ally, and—by all accounts—a true mensch.

“What I accomplished,” Hannah reflects years later, “was simply not walking away. It’s hard to stay at the table, but if we walk away from each other, nothing will ever get better.”

Excerpted from THE AMEN EFFECT: ANCIENT WISDOM TO MEND OUR BROKEN HEARTS AND WORLD by Sharon Brous with permission of Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Sharon Brous, 2024.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.