Renowned Author Pico Iyer Traveled the World in Search of Paradise and Joy in the Face of Suffering. Here's What He Found...

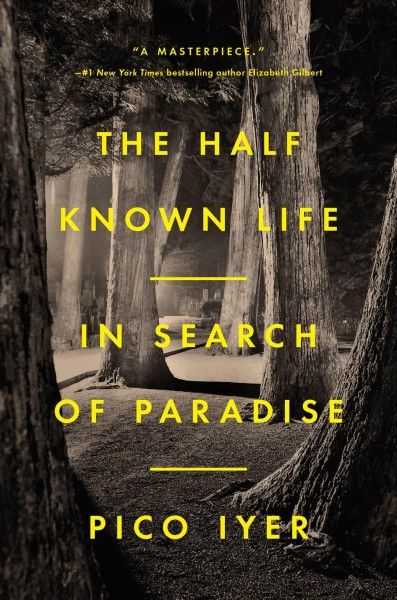

In his new book, The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise, author and journalist Pico Iyer repeats, in varied words and sentences, the truth of his quest: “What kind of paradise can ever be found in a world of unceasing conflict?” It’s a heady inquiry; an attempt to find out the impossible, even. But the fact that Iyer set out to answer it anyway is one of a million reasons this book deserves to be read.

Compiling 48 years’ worth of his vivid reporting across the globe, Iyer presents a soulful examination of what the idea of paradise—or “calm and contentment,” as he tells us—means to people around the world. Yet from its first page, the book defies expectations. Iyer doesn’t highlight places that quintessentially conjure ideas of paradise, like sun-soaked islands and dreamy beachsides. He goes to countries plagued by wars and strife, such as Iran and Northern Ireland, to seek out the hope and joy found by its people.

What did he find? One finite answer to paradise may be too immeasurable to write, as it’s so personal. But Iyer did find illuminating throughlines, which he graciously shares with The Sunday Paper. “My hope is that this is a book about hope,” he tells us. “And that it's a book that looks realistically at all the conflicts in our very difficult world and believes that in the face of that, there's still beautiful possibilities.”

A Conversation with Pico Iyer

You've traveled the world to cover so many assignments and speak to countless people. What drew you to compile your experiences to write about paradise?

It was two things, both that rose from the pandemic. As soon as the lockdown was declared in California, my mother, who was then 88, was rushed to the hospital. I was in a little apartment in Japan, but as soon as she was out of the hospital, I had to fly back through these three ghost-town airports to be with her. I was with my mother for much of the next 15 months as she was nearing the end of her life. And all of us during the pandemic, of course, were in this state of acute anxiety, and I think many of us were addressing this basic question of How do we find paradise, or rather calm and contentment, in the midst of adversity? And in the thick of all life challenges, how do we find a better life and a better world?

I think, unexpectedly, many of us came to our conclusions and found that the pandemic was opening doors as well as closing doors and reminding us of possibilities we'd forgotten. So part of it was addressing how we can find calm and contentment in the middle of real life and the face of this. And secondly, because I was not traveling as much, I had the perfect moment to look back on my 48 years of constantly crisscrossing the globe and my 48 years of traveling with the Dalai Lama, and 31 years of spending time in monastery to see what it all added up to. In the normal run of things, I might not have had an interview that allowed me to think back on my whole life like that.

Now that it's completed and it’s in people's hands, how do you feel?

That’s a great question. I'm not sure anyone's ever asked me exactly that. Writing is a great adventure in life. And although, as you say, I've been lucky to travel a lot, I feel that the real journey takes place when I'm back home, making sense of everything I've seen and trying to figure out what really moved me or surprised me or maybe stirred me to change my life after any travel. There are about 10 disparate places in this book, and I would never otherwise have thought of putting them together into a single inquiry, posing questions I can never answer. I love the fact of the luxury of spending a lot of time thinking about all these places and putting them together.

What is striking in your book is this tension between paradise—or as you say 'calm and contentment'—being either a physical place or something that exists within us. A few examples include when you wrote about how Kashmir during World War II was a place of peace for your mother, and how Belfast provided endless radiance for Van Morrison’s songs despite its bloody history. How much is paradise and calm up to what’s inside us versus where we are?

I think all of us know, at some level, that paradise is within. But I came to think that paradise was just a function of how we see the world and a matter of looking at the world in the right way, even during the pandemic. In the heart of the pandemic, my wife and I were finding things and doing things, taking walks along the beach every afternoon, that we would never think to do otherwise and they were as richly rewarding as anything we've enjoyed in our travels across the world.

The first surprising thing about this book in addressing paradise is that I don't write about Bali and Tahiti and Seychelles and other wonderful places I've been to that are the travel-poster versions of paradise. I go to these places of conflict and war zones and difficulties precisely because my question to myself was: How can one find peace in the middle of this ever more conflicted and divided world? Van Morrison, growing up in the middle of ‘The Troubles’ in this modest house with no advantages at all, still somehow found this radiant vision of Arcadia that he's passed on to so many millions for so many years, is the perfect example. And in my mother's case, it was wonderful when she remembered her idyllic girl visits to Kashmir, that in itself was exciting to me. But then I realized that was during World War II, and it wasn't as if she was ignoring the war, but as a little girl in India, she could find duty and wonder that stayed with her all her life.

That speaks to hope, which is such a strong throughline in the book. You wrote that “hope and history were in hourly collision” about your time in Kashmir…

So many people I know today feel desperate about the world and worried about so many things, political and environmental. Yet I'm not sure we can even address those problems unless we can find a certain degree of clarity and hope.

I live in Japan. If I go to a temple in Kyoto, often written on the ground when you enter are the words ‘look beneath your feet.’ And I think that's almost the essence of this book. In other words, don't look to Shangri-La. Don't hope you'll find paradise if you get to Tahiti, because it may be paradise for you on a 10-day vacation, but it's probably not for the locals. And if it is paradise, you may be corrupting it a little by being there. So don't look for an external paradise. Remember that it’s within. But also remember that you can maybe find it in any circumstance, including the difficult ones in which we all live.

I invoked a term that's often associated with Buddhism, which is about joyful participation in a world of sorrows. For everybody, sadly, it is a world of sorrows, because we're always going to lose things, including our own lives, and we're always going to face challenges. But how can we live joyfully in the midst of that? That’s one reason at the midpoint of the book, I bring in the Dalai Lama, who is the perfect model of that. He has suffered so much, yet one of the main things His Holiness is known for are his constant smile and his infectious laugh, and his robust confidence. Amid a very challenging, tumultuous life, he's radiating confidence and kindness, that’s a model of what maybe all of us can find in our own lives.

Pico Iyer is the author of fifteen books, translated into twenty-three languages, and has been a constant contributor for more than thirty years to Time, The New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. His four recent talks for TED have received more than eleven million views. Learn more at picoiyerjourneys.com and order his new book The Half Known Life: in Search of Paradise here.

Question from the Editor: What has been an unexpected means of paradise, or calm and contentment, you've found in your life?

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.