Are You Craving More Courage, Hope, and Purpose? Nicholas Kristof’s New Book Will Inspire You to Find It

Nicholas Kristoff first learned the power of a well-written editorial when he was in eighth grade, writing for his student newspaper. He argued against a school rule that said girls couldn’t wear blue jeans to school and says his campaign to fight this dress code injustice had three aims: to impress girls, to give him something to talk about with girls, and to overthrow the patriarchy.

The Yamhill Grade School principal changed the dress code. And Kristof’s career as a journalist on a mission to have impact, was born.

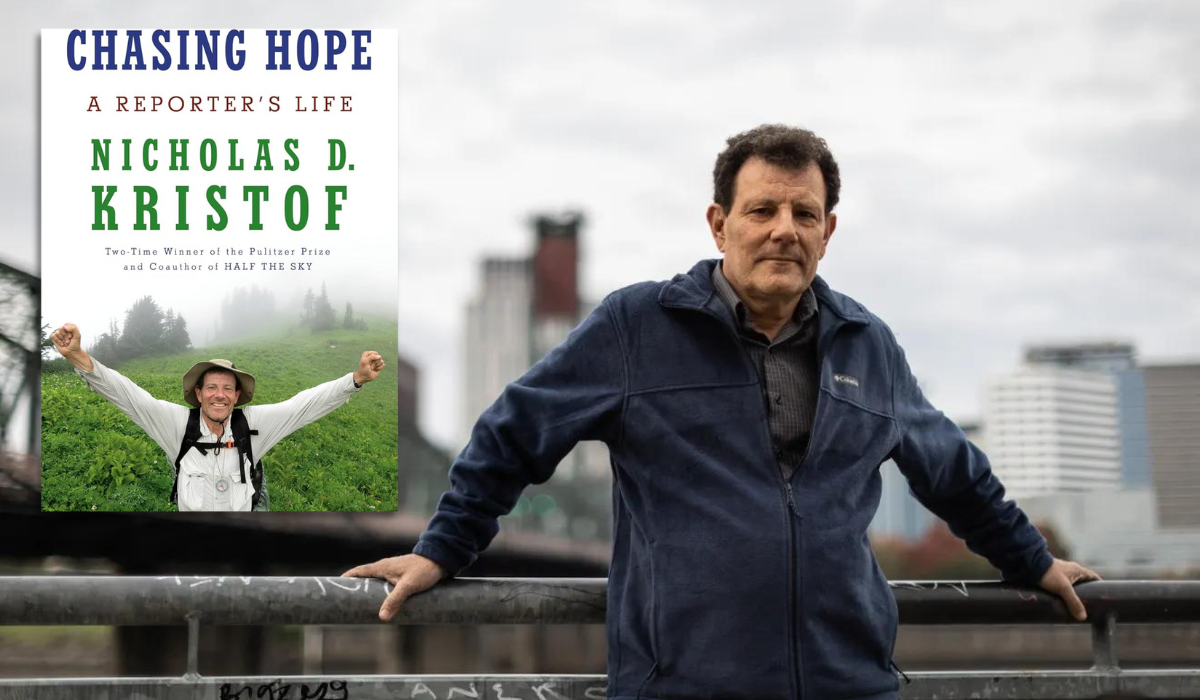

In his new memoir, Chasing Hope, Kristof recounts many of his exciting, and at times terrifying, assignments—from the Tiananmen Square protests and the genocide in Darfur to the Yemeni civil war and the opioid addiction crisis among working-class America. He has seen the darkness in humanity. Still, he finds reason to hope.

“Side by side with the worst of humanity you invariably find the very best,” Kristof tells The Sunday Paper. “I end up feeling a little better about humanity when we are truly tested.” Read on for our conversation.

A CONVERSATION WITH NICHOLAS KRISTOF

We’re at a sad moment in time when trust in journalism is in jeopardy. What do you say to those who are losing faith in the profession?

When democracy is stressed and so much is at stake, journalism has never been more important. I think this is a real test for journalism in an enormously important moment, and thus really fulfilling for journalists. On the other hand, there is a real problem that we don’t have a business model for a lot of what we do, and it’s not obvious how young journalists of enormous talent who enter the profession will be compensated. Regional and local newspapers are in a real financial crisis. I don’t have a solution to that. But in terms of the importance of what journalists do every day around the country, I deeply believe in that. I think at a time of disinformation and misinformation, real, accurate information has never been more important.

There’s a lot all of us can learn from journalists when it comes to asking thoughtful questions and actively listening to answers. What’s your best advice when it comes to doing both?

Journalists bring an important skill set of communicating their ideas and listening and understanding where other people are coming from. I think the first step is a certain amount of charm—getting people to relax and feel that you’re not a threat. And then listening and asking respectful, civil questions about the implications of what they’re saying and also of the roots of what they’re saying. If done well, that is also an engaging process for the person being questioned.

How do you stay objective—or at least try to remain neutral—when you’re talking about topics on which you have a strong point of view?

I think two crucial qualities for a journalist—and frankly, for any citizen—are genuine curiosity and a certain amount of humility.

I think humility is useful because we all have screwed up enormously. Look, I’m a liberal. I think that we liberals forget how many issues we have badly screwed up on over the last 100 years. One of the crucial issues was communism; so many on the left really bungled the response to that and were soft on Soviet communism and soft on Maoism. Meanwhile, the right managed to screw up on civil rights, on women’s rights, on Iraq, and on Vietnam. If you look at the pandemic, the right was often wrong on vaccines and the left was wrong on school closures.

We all have much to be humble about it, but I think the challenge—whether for journalists or for citizens—is to be able to take a moral stance and stand unflinchingly for what you believe to be right while also understanding that you may be wrong. I think that reduces the sanctimony of what we say. It reduces the self-righteousness and the finger-wagging quality of our pontificating. And it also makes what we say more persuasive.

The news feels heavy these days, and almost surreal. How do you chase hope, despite the facts that inspire despair?

What a difficult time. We’ve got wars not only in Gaza and Ukraine that are getting a lot of attention, but brutal mass atrocities in Sudan and Myanmar, we’re teetering on the edge of famine in Ethiopia, and we’re seeing enormous threats to democracy in this country and to some degree, in Europe.

But we’ve always been under stress. Somebody responded to an excerpt from my book in The New York Times and said, “The 1960s was much better.” And I thought, really? The 1960s—when we had assassinations of JFK, RFK, Martin Luther King, Jr.? When we had civil rights workers being killed? When we had Jim Crow? When we had the Vietnam war raging and in addition to our soldiers being killed, we were slaughtering the Vietnamese? I mean, so much was going on. There have always been these challenges, and we get ourselves into terrible messes, and periodically we manage to extricate ourselves if we work together at that process.

I’m buoyed by the fact that in my career, I’ve seen enormous progress in human rights and human wellbeing and health and mortality and morbidity. And side by side with the worst of humanity, you invariably find the very best. I go off and I see warlords busy slaughtering people and committing mass rape, but side by side I’ve seen these incredible human beings who managed to fight back and assert their dignity, humanity, strength, and resilience.

I end up feeling a little better about humanity when we are truly tested.

What helps you stay above the noise so you can do the work you do?

When I first got my column, I thought, Oh, wow, I’m going to change people’s minds twice a week. And I realized quickly it doesn’t work that way at all—that when I write a column about an issue that’s about a topic people have already thought about, I’ve convinced almost nobody.

If I write about Trump, Gaza, guns, or abortion, people who start out agreeing with me think, “Great column!” People who start out disagreeing with me think, “Kristof completely missed the point.”

What I’ve learned is that where we in journalism really have power is not so much the ability to change minds on topics they’ve thought about, but the ability to project new issues onto the agenda and make people think about things that they hadn’t thought about before. It’s a chance to make people spill their coffee about something disturbing.

That is what I aim to do. I don’t always manage it. But that is where I feel I have had impact and it’s where I look for impact.

What do you hope readers will take away from your memoir?

In some ways, this is a love letter to journalism. The journalistic toolbox, in many ways, is a toolbox about trying imperfectly to bring about change. And I think that that toolbox can be adapted by many kinds of people for advocacy and persuasion, and for trying to address the challenges around us.

Ideally, I would like people to put down Chasing Hope feeling a little more hopeful, feeling a little more self-efficacy, feeling that they could actually do something. I would love it if that were about journalism. But I think in many cases, it will be about trying to persuade people to engage in advocacy and to try to make this world a little bit better.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.