I Missed All the Warning Signs of My Sister’s Young Dementia. This Is What I Wish I Knew Before It Was Too Late

In the far corner of the produce section at Shaw’s Market, I reached for a grapefruit to inspect, keeping in mind the only bad thing about a New England winter coming to an end is that grapefruit season would end soon, too. Placing one, then another, Ruby Reds into a plastic bag my gaze lifted, and I saw my sister at the salad bar tuck something into the fold of her thick winter coat. I recognized her immediately, wearing the same coat I’d bought for her at the thrift shop. It was the shine of silver foil that caught my eye. Most likely fresh fruit from the salad bar, packaged in a foil to-go container. Lyndy loved fresh fruit.

As the doors closed behind her, the streetlights illuminated Lyndy’s small frame, and a familiar heartache tugged at me. I saw her matted hair, so snarled and tangled that only scissors could help. Her hair had been long and silky once, soft as angora. Disappearing now from my view, she shuffled as she walked, her feet sockless in her unlaced boots. I wiped my eyes with the back of my hand, breaking the trance of watching my sister leave the store with her stolen goods. The streetlamp had an aura of ice crystals. It was cold outside. Cold, dark, and scary. Not a place where Lyndy should live.

I walked over to the deli counter, took my number in line, and kept thinking about Lyndy while I waited. Where was she at this very moment? Had she walked back to the abandoned car tucked in the woods behind the old Victorian in town? Was she sitting in the backseat eating her shoplifted dinner? Was she warm enough? I hoped she had a blanket, or even a sleeping bag, spread across her lap, tucked beneath her thighs.

And then something clicked inside me and instead of feeling pity or worry, I felt angry. I crumpled the deli ticket and tossed it in the basket. I couldn’t let Lyndy get away with this. Why should I go to work every day, earn a paycheck to buy groceries, and she just thinks she can walk in here and take whatever she wants? Oh, hell no.

I wanted to speak to the store manager, to tell him about Lyndy stealing, but when he approached with a smile on his face and he asked if he could help me, I hesitated. “Yes, well,” I had practiced this in my head so many times. That woman, the one with the tan coat, the one who is filthy and smells, you know the one, right? Well, she steals food from your store. But the words froze in my mouth. If I told the manager that Lyndy was stealing from him, where would she get food to eat? “No.” I stepped back and shook my head. “I’m sorry for having troubled you.”

I left my shopping cart near the deli counter and headed to my car empty-handed.

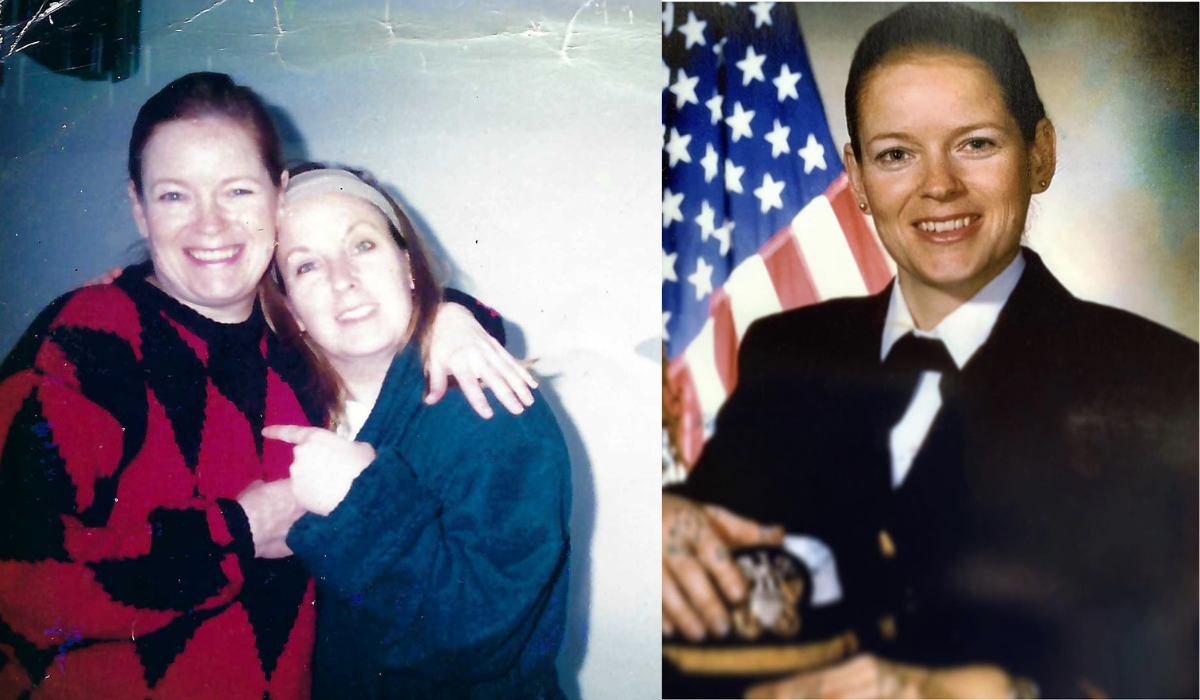

Over the past few years, our family had watched Lyndy stray as far from normal as possible. Where once she had been a Lieutenant in the Navy, now she couldn’t hold a job at Burger King. Where once she had provided a loving home for her three sons, she now lived out of an abandoned car—huddling in a stranger’s basement to stay warm—and lost custody of her youngest son. Where once she had taken pride in her appearance, she now wandered the streets in the same baggy secondhand clothes—unbathed, a vagabond. Growing up, I had wanted to be just like Lyndy, and now I wanted to be nothing like her.

This physical change in Lyndy’s appearance—from dressing in her crisp military uniform, her hair pinned up in a bun, her eyes bright and lips glossed—was drastic in comparison, but the change occurred so slowly that it is hard to pinpoint when it really began. But I do remember how it began, and I want to share my story so others might recognize the signs and be able to spare themselves years of either undiagnosed or misdiagnosis.

I call them red flags, and with hindsight, they are invaluable. The first red flag I recall is when Lyndy was 44-years-old. She and I were business partners in a successful accounting firm we founded together called Vital Office Systems, Inc. One day, while Lyndy took her sons on vacation to New Hampshire, I checked in on her client who had just been granted a loan based on the financials Lyndy provided to the bank. I remember the precise moment when I uncovered a fatal error in Lyndy’s accounting. It hit me like a bucket of ice water. When confronted, Lyndy played it off as no big deal. Eventually, we began losing clients due to Lyndy’s errors and I knew I needed to dissolve our business to save my own reputation.

Slowly, the red flags began to compound. She forgot to pick up her youngest son at the airport when he returned from a visit to his father. She couldn’t sew a simple skirt, and yet had sewn her wedding dress two decades earlier. At Thanksgiving, she’d forgotten how to make the gravy although she was acknowledged as the creative chef in the family. These red flags happened so gradually that we were unable to connect the dots.

When Lyndy didn’t pay her rent, she was evicted, and became homeless living out of her car until the engine seized because she neglected to add oil. She no longer bathed or did any personal grooming but none of this mattered to her. Not being jobless, homeless, losing custody of her son, not even her relationship with her sisters seemed to matter anymore. Peggy and I shared taking Lyndy to one doctor after another—retelling the story from the beginning—how something was wrong with our sister, and we needed help. Peggy took her to the Counseling Center at the University of Rhode Island. I took her to the psychiatrist a friend recommended, and to a co-worker’s therapist. At one visit, I was sent home with a lunch bag filled with samples of an antidepressant and was told to give them a try. We both took her to South Shore Mental Health Center.

It’s depression, they all said.

It’s not depression, we insisted.

It’s alcoholism, they said.

She hasn’t had a drink in months, we argued.

But none of us—not the professionals and not her sisters—could see from the outside what was going on inside. As we took Lyndy from one doctor to another searching for answers, neither Peggy nor I understood there really were no answers. This went on for years, until one arctic cold January morning when temperatures reached seventeen degrees below zero. Lyndy was found face down on the bike path and rushed to the emergency room. There, a simple brain MRI was performed, and it finally explained Lyndy’s bizarre behavior and her gradual downward spiral. She had a rare brain disease referred to as frontotemporal dementia or Pick’s disease, a behavioral variant of FTD.

Though fifty-two years old at the time of her diagnosis, Lyndy had the reasoning of a four-year-old child. She had lost a profound amount of her frontal lobe, which robbed her of the ability to understand such things like if there was a fire, not to touch the door handle. This meant Lyndy required round-the-clock supervision and because she was considered a wanderer, a locked dementia unit. It is difficult to find a suitable home for a loved one so young with dementia, but eventually we did and for five years Lyndy lived on the third floor at Mount St. Francis in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Eventually, the insidious disease that atrophied her brain stole Lyndy’s words, stole her memories, and stole her from us. Hospice had been called in two years prior because of her inability to thrive. And on her son’s twenty-first birthday, Lyndy passed away. She was only fifty-seven years old.

Lyndy’s brain was autopsied as part of a study at Brown Medical School. An abundance of Pick cells was found, and advanced Pick’s disease was confirmed. The average weight of an adult human brain is 1,300 to 1,400 grams. Lyndy’s brain weighed 948 grams.

According to the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration’s website, the hallmarks of bvFTD are personality changes, apathy, and a progressive decline in socially appropriate behavior, judgment, self-control, and empathy. Unlike in Alzheimer’s disease, memory is usually relatively spared in bvFTD. People with bvFTD typically do not recognize the changes in their own behavior, or exhibit awareness or concern for the effect their behavior has on the people around them.

To know the signs and know the symptoms, please refer to the link on their website.

Keep up with Deborah on Instagram.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.