My Father Was on the 99th Floor of the South Tower on 9/11. Here are 3 Lessons I’ve Learned About Healing in the Two Decades Since

I still don’t know how to bring it up when the date is thrown around in conversation.

I’ll hear it mentioned casually in millennial podcasts, used as a touchpoint—the beginning of the timeline of a 20-something’s conscious memory.

When it’s mentioned, people share their stories candidly; they remember TVs being rolled into their middle school classrooms or the innocent greetings they had with colleagues that morning before they found out the news.

Sometimes someone will share the loss closest to them, a friend of a friend’s uncle was FDNY, and they’ll mutter, “That was an awful day.” Most of us have our own story about it—the flashbulb memory that's forever stuck in our minds, marking time before and after.

When I share my experience of that day—“I lost my Dad on 9/11, he worked on the 99th Floor of the South Tower, I had just started Kindergarten”—I’m met with uneasy expressions or the exasperated “Oh, I’m so sorry!”

I thank them in an attempt to dissipate the discomfort, but there’s no tidy response that eases the burden I just shared. So, most of the time I keep my disclosures brief.

It’s complicated to share the personal side of a public tragedy—one that the world watched unfold in real time as we stared at the same images on our respective TV screens, experiencing entirely different outcomes.

Some assume that losing a parent at a young age is less painful, perhaps assuming less time to get to know the person you lose means less grief to endure. This isn’t the case for me. Speaking with other young adults who lost their parents that day, the tragedy on 9/11 robbed us. The time and relationships we should have had with our parents were stolen before they had a chance to happen.

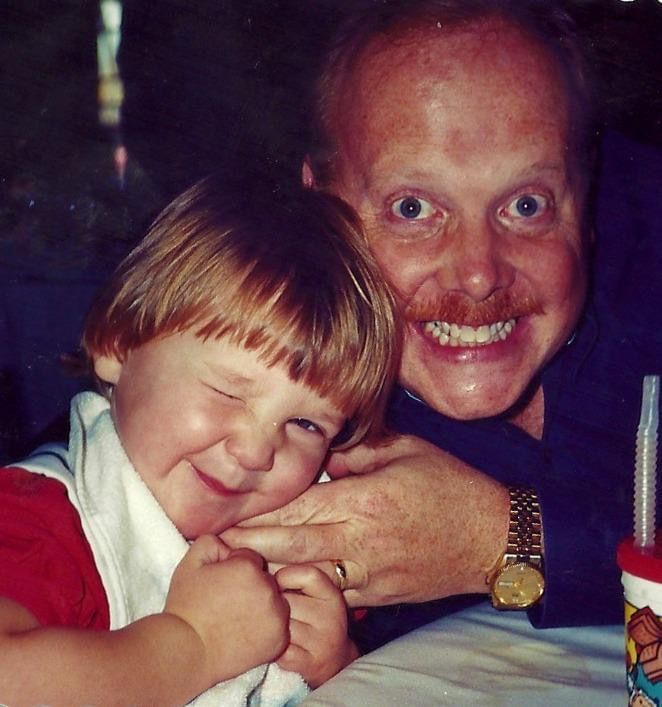

The memories I have of my Dad are limited, contained to those five short years. I can remember the summer days we drove down to the Jersey Shore as a family and the nickname he gave me (Nicolinie is a weenie) that embarrasses me to this day. There was also one time we were sitting in his truck in the driveway and my sister stole a sip of his beer, and we all burst into laughter. There’s only so much I’ve been able to learn in his passing. I know his favorite musicians (Pink Floyd and Roger Waters), his drink of choice (Jack and Coke), and how he went from being an only child to embracing a chosen family (fraternity brothers and my mom’s clan).

I’m coming to accept that I’ll never truly know my Dad in the ways I wish I could. Now, 21 years later, I find myself searching less about him and more about what losing him that day means for me.

No version of that day will ever explain why my Dad was taken from us in an instant. In this anti-fairytale reality, the villains won when 2,977 people took their last breath and our nation froze in fear.

This loss has become a part of me and healing has not been linear. After all, there’s no path to follow from a devastated place to another, happier one. Healing is messy and muddled, but it is possible for each of us.

I have healed in the years since my father died—and I’ll continue on this healing journey for the rest of my life. Here’s what I’ve learned so far along my way.

Lesson No. 1: You have to honor your grief.

When I was a tween and teen, I convinced myself that I hardly knew my dad. This meant spending years of my youth secretly wondering why I cared so much about his death. I was grieving the life I was supposed to have with him—the nights we should have spent at the dinner table fighting over my math homework, the secrets we would’ve kept from my Mom, the jokes only we would’ve had with one another. Instead, there was a vacancy that one parent alone could not fill despite my Mom’s best efforts.

Grief is multifaceted, layered, and messy. It is crying at stoplights when I see a young Dad and his daughter, and it is the guilt I feel for not celebrating my father’s birthday every year. There is no expiration date on your grief and no warning signs for when a wave of it will take you down. Grief follows each of us in curious and sneaky ways. Yet what I’m sure of is this: We have to honor our grief. After all, grief is, at its core, the deepest form of love.

Lesson No. 2: You can share your story on your own terms.

I lost my dad to a national tragedy, one that has made headlines each and every year and one the nation vows to “never forget.” The media attempts to make the unbelievable believable. Interviews with loved ones about their losses are revered as inspirational and brave.

And while there is power in being vulnerable—allowing others to see your mangled and mending heart—there is also power in keeping your story truly yours. Honoring your healing requires both tender and fierce self-compassion. You have to give yourself the time and space to process your experience with delicate care, and fiercely maintain your boundaries in the process.

Whether you decide to write it down, splatter it on a canvas, capture it in film, or speak openly, let your story be a gift to yourself first. You owe it to yourself to sit with this story, revel in your strength, and choose who gets to hear it.

Lesson No. 3: You have to be kind to your mind.

Trauma and hardships can change our brain. They shift us into a state of high alert, protecting us from the next threat. Trauma is meant to be adaptive—to give us an edge that allows for our survival, just as our ancestors needed. But in our modern world, our precious minds and bodies suffer when we experience prolonged hypervigilance. We can get stuck in a place of fear for what may happen next, which takes us away from being in the present moment.

Being kind to your mind means acknowledging the toll your brain has taken in grief. It is tending to the trauma, the sadness, the pain, and all of the feelings that are coursing through you. It is giving ourselves grace when we are triggered unexpectedly. It is doing the hard work and going to therapy, even when it doesn’t feel good. It is choosing to befriend your most vulnerable self and doing it solely for you.

Nicole C. Foster is a board-certified health and wellness coach and writer. She is a health coach at Lief Therapeutics, a mental health start-up. Her personal writing has been featured in The Cut, and she is currently working on a memoir. She is co-author of the forthcoming book Courageous Well-Being for Nurses: Strategies for Renewal with Donna A. Gaffney, to be published by Johns Hopkins University in 2023. You can find her at @NicoleCFoster and www.NicoleCFoster.com

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.