Heart Attack Symptoms Look Very Different in Women and Men. We Asked Two Leading Cardiologists About What All of Us Need to Be Aware Of at Every Age

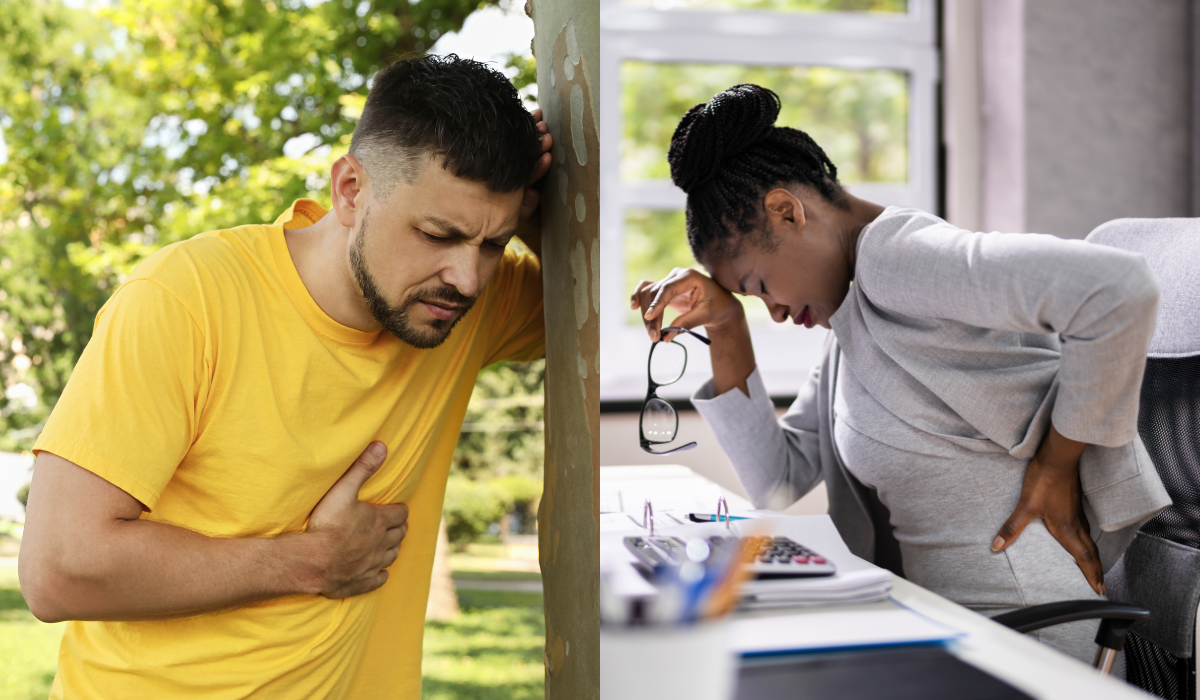

When you think about the signs of a heart attack, what comes to mind? Crushing chest pain? Shortness of breath? Pain radiating down the left arm?

While these are, in fact, well-known indicators of heart attack, there are several lesser-known symptoms that can easily go unnoticed—and they can look very different in women than they do in men.

To make sure these sneakier signs are on your radar, The Sunday Paper sat down with cardiologists Jayne Morgan, MD, and Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD. Here’s what they want all of us to know so we can recognize the signs and take immediate action.

A CONVERSATION WITH JAYNE MORGAN, MD

What are some of the signs of heart attack in women that too many of us don’t know about?

Women’s symptoms can be different, and often less dramatic, than the crushing chest pain, chest tightness, and shortness of breath that drives most men to the hospital. Sometimes symptoms are the same, but they can also be more nuanced in women and manifest in nonspecific ways, such as nagging back pain; jaw pain that feels like a tooth ache and inspires you to go to the dentist rather than the emergency room; feeling run down or tired; having flu-like symptoms, like nausea or vomiting; dizziness; and shortness of breath without any chest pain.

Oftentimes these symptoms feel more pronounced at night, because we finally slow down enough and get quiet enough to experience them whereas during your busy day, these symptoms might be easier to ignore.

Given this, you can see how so many women minimize these symptoms. Who isn’t tired? Who doesn’t have back pain? What woman isn’t so busy that she powers through her day even if she doesn’t feel great because she has so much to do? Sadly, even many physicians don’t take these symptoms seriously and recognize them as signs of a possible heart attack. And by the time women seek help, they’ve often had a heart attack.

Why aren’t more women aware of these differences in how heart attack manifests in women vs. men?

Women’s symptoms of heart attack are seen as atypical. Think about that for a moment: If women are the ones with atypical symptoms, it means everyone learns what the main symptoms are and we have to learn additional information about women. But who’s to say women aren’t having the typical symptoms? Thinking of the signs of heart attack in women as atypical means women aren’t the focus—men are. It’s a reflection of our male dominated society, and the fact that not enough women are in clinical trials.

What are some of the risk factors of heart disease in women that not enough of us realize or talk about with our health care providers?

When a woman is pregnant, it’s essentially a stress test for your heart. This means that complications during pregnancy that involve high blood pressure—like preeclampsia (a condition that causes high blood pressure and can cause organs, like the kidneys and liver, to not work normally), eclampsia (seizures that occur in pregnant people with preeclampsia), and diabetes in pregnancy—are essentially signs that you’ve failed this first cardiac stress test.

The good news is that once the baby is delivered, these conditions resolve on their own. Yet if you’ve experienced these complications during one or more of your pregnancies, you are at an increased risk of heart disease—some estimates say that risk is twofold—and you should be referred to a cardiologist.

Even if you had these complications during pregnancy many years ago and you’re well beyond your childbearing years, it’s a good idea to talk to your primary care physician and see if a cardiac workup is recommended. If your physician isn’t aware of this connection between pregnancy complications and heart disease risk, ask for a referral to a cardiologist. It also means you’ll want to put a big focus on preventive care, and more aggressively treat high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. You’ll also want to focus on the lifestyle factors—like a healthy diet and exercise—that you can control.

What do we know about the connection between menopause, certain symptoms of menopause (like hot flashes), and heart disease in women?

As estrogen levels drop during the perimenopause transition and after menopause, we know that a woman’s risk of heart disease goes up. We believe this is because estrogen is protective of the heart.

Part of the development of heart disease is due to atherosclerosis—the thickening or hardening of the arteries caused by a buildup of plaque in the inner lining of an artery. We know atherosclerosis is triggered by things like high cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, and diabetes. But we also know that these are things that keep the body in an inflammatory state—and estrogen has anti-inflammatory benefits.

We’re also beginning to understand that hot flashes can be an indicator of a risk for heart disease. The more intense hot flashes are during the menopause transition and the longer they last, the higher a woman’s risk of developing heart disease. We know estrogen is a key part of the story, but there’s likely a complex and multifactorial process going on and the fact is we just don’t have enough clinical trials yet to understand exactly what’s happening.

What’s your best advice for women when it comes to preventing heart disease and heart attack?

Well, we need more women to take part in clinical trials so we can understand how to mitigate the risk of heart disease in women. In an ideal world, more women would be the principal investigators of clinical trials. That’s because people are most likely to enter clinical trials if they are approached by their physician—and oftentimes that happens because their physician is an investigator on the trial. Right now, more than 95 percent of principal investigators of clinical trials are white males. This needs to change. Until it does, all of us can go online and search for clinical trials for which we might be eligible. Check out your local medical center or academic institution to see what trials they have available. You can also bring up your interest in participating in research with your doctor, who can help you find a trial to join.

Knowing the signs of heart attack and risks of heart disease can also go a long way toward helping you advocate for yourself. We have a high tolerance here in the U.S. of women’s suffering. Men don’t suffer. They get their problems taken care of. But women suffer. It’s part of what’s accepted and expected. And it’s up to us to say we’ve had enough.

A CONVERSATION WITH DONALD M. LLOYD-JONES, MD

First, what exactly is a heart attack?

A heart attack happens as a result of plaque in an artery that has ruptured, either because of acute stress (something like shoveling snow) or because of inflammation due to being fed enough cholesterol. When plaque ruptures open and the contents of the plaque get exposed to the bloodstream, the blood does what it's supposed to do and says, “Oh, there's a tear in the artery here, I have to seal that up.”

The blood then forms a clot, and if that blood clot is big enough, it will actually block the entire artery. As soon as the artery is blocked, no blood is going downstream, which means any muscle downstream from the blockage is not getting oxygen, nutrients, and all the things that it needs. Within minutes, those heart muscle cells will start to die. That's what we're talking about when we talk about a heart attack.

Can you describe some of the symptoms of heart attack that many patients find surprising?

Well, the classic sign most people are well aware of is crushing central chest pressure. Patients often describe it feeling like “an elephant is sitting on my chest.” That's still the most common symptom and certainly a sign people should not ignore. It is more common for men to experience this sudden, intense chest pain or pressure than women, who often experience more subtle symptoms.

As for the atypical signs of heart attack, severe gum pain that’s not from a toothache is one that surprises many. People will describe it as a gnawing gum pain that goes away when they slow down and relax. Likewise, upper chest symptoms—shoulder pain, upper back pain, a feeling of heartburn, indigestion, or burning in your chest—can also be signs of a blocked artery in your heart.

Any sensation that we're feeling requires whatever organ is involved to report back via nerves to the brain. So, if you’re having a heart attack, your brain is telling you that you feel heavy pressure in your chest—it's not that there's actually pressure. Each of us experience these symptoms from our heart in different ways because we're all wired somewhat differently. So different nerve tracts may be reporting back to different parts of our brain.

Do we know what percentage of heart attack patients will have less dramatic symptoms than the crushing chest pain symptom many of us associate with heart attack?

A lot of people are trying to answer this question, which is tricky. The literature would suggest that up to half of heart attacks go unrecognized. If we're following the same person for years over time in a study, oftentimes they come in one day and their electrocardiogram (EKG, which records the electrical signal from the heart to check for heart conditions) shows that there's been heart damage.

Even if someone has had a heart attack since we last saw them, they often won't have recognized that they had a heart attack. However, when we really probe and ask if they remember anything, they will often report remembering a day with really bad heartburn, or a day when they suddenly felt wiped out for no reason and it took them a week to recover. In retrospect, we can say, ‘Well, that was probably when you had your heart attack, but you didn't have the classic symptoms so didn’t go to the hospital.’ We actually think about half of heart attacks go unrecognized in that sense. Not necessarily asymptomatic, just unrecognized.

What are the best preventive strategies people can take (in addition to knowing these less-talked-about signs of heart attack) to avoid a heart attack?

The important things are what the American Heart Association calls Life’s Essential 8. These are the things that will not only help you live longer, but they will help you live healthier, longer— without heart attacks, strokes, or even heart failure. They also help you prevent cancer and other chronic diseases of aging.

It’s important to keep in mind you don't have to do all of these eight things at the same time. Choose one you're ready to work on and just focus on that one. That will go a long way towards reducing your risk of heart attack or heart disease, because these eight health behaviors and factors are interrelated.

Jayne Morgan, MD, is a cardiologist and the executive director of health and community education at the Piedmont Healthcare Corporation in Atlanta, the largest healthcare system in Georgia. Dr. Morgan has been named to the Health Equity and Covid Task Force for the Governor of the state of Georgia and selected to support the Department of Health in its series of "Ask The Experts". Additionally, she serves as a CNN medical expert contributor and is the owner and creator of The Stairwell Chronicles, a social media series directed towards addressing questions surrounding Covid vaccines in a conversational format. To learn more, visit drjaynemorgan.com.

Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, is the chair of the department of preventive medicine and a professor of preventive medicine, cardiology, and pediatrics at Northwestern Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine. From 2012-2020, Dr. Lloyd-Jones was Senior Associate Dean for Clinical and Translational Research and Director of the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences (NUCATS) Institute. In 2021-22, he served as President of the American Heart Association.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.