Gillian Anderson Asked Women to Share Their Sexual Fantasies. The Result Is a Riveting Bestseller

To prepare for her role as Dr Jean Milburn, the hilarious and compassionate sex therapist in the hit (and now concluded) series "Sex Education," Gillian Anderson picked up My Secret Garden. The actor was hoping the 1973 book, a compilation of real women's letters about their sexual desires, would inspire her. It did—and cracked open a portal. Anderson was struck by the intimacy and rawness of the women's letters. The richness and limitlessness of their yearning. She couldn't help but wonder: What are women's fantasies today, now 50 years later?

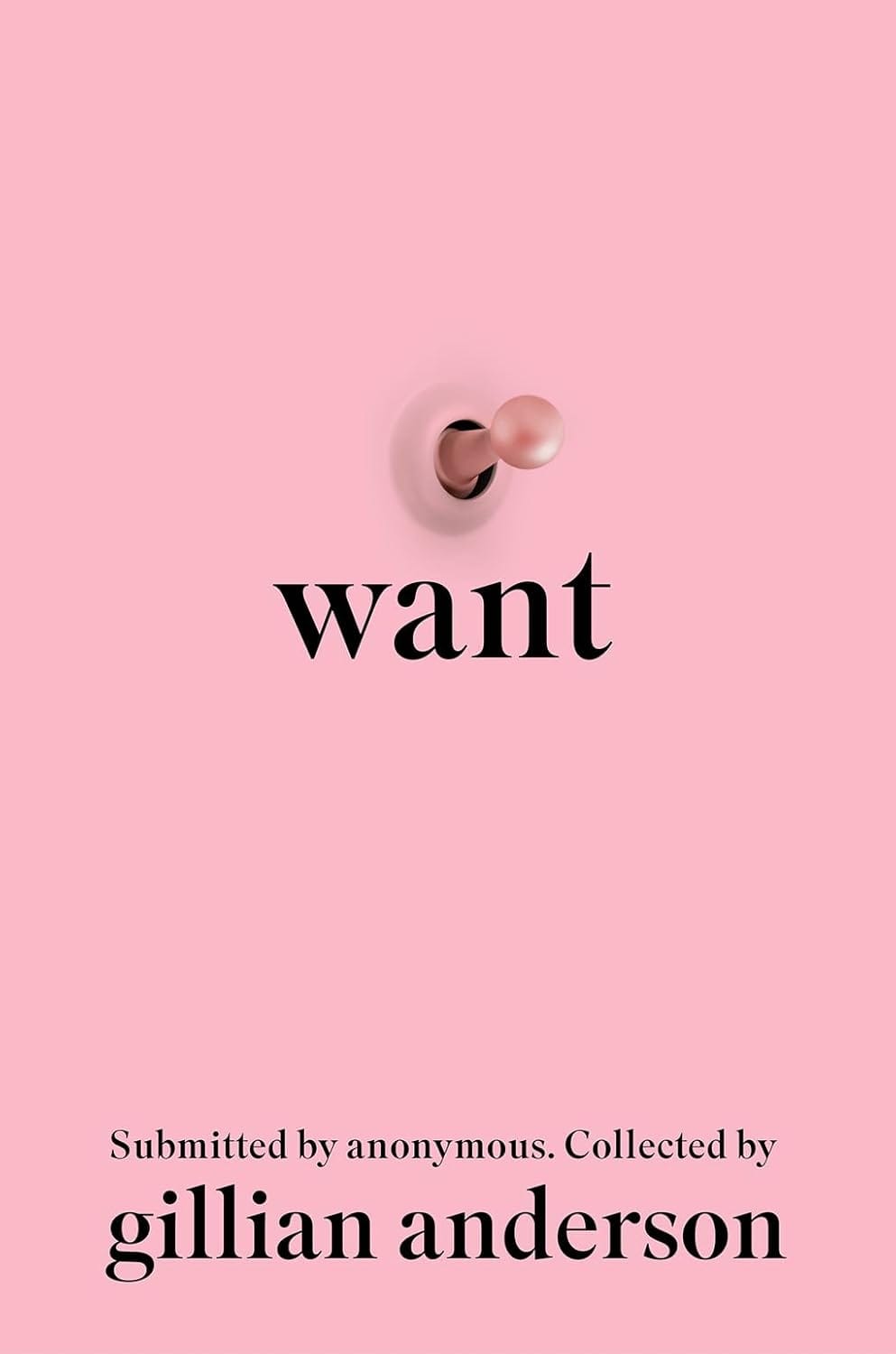

Anderson's curiosity unspooled into a project. She and her publishers set up a way for women around the globe to anonymously submit letters about their unabashed sexual desires. The letters poured in—thousands of pages' worth—and ultimately became Want: Sexual Fantasies by Anonymous, the new bestselling book that Anderson compiled. "We had received enough entries to fill at least eight volumes," she writes in the introduction. "Clearly, there was a need."

Women's colossal desire to share their inner erotic worlds, combined with the book's massive popularity, speaks to the grander themes revealed in Want, which Anderson is passionate about discussing. People are hungry to express their truth. We desire liberation, wildness, and the freedom to be ourselves.

"It makes me very emotional," says Anderson, who submitted a letter to the book, over Zoom. "It's in the communion of talking through what this means that I, too, am being shown what it means and the importance of us being able to have this conversation."

A CONVERSATION WITH GILLIAN ANDERSON

It's impossible not to start by saying thank you for creating this book. It is so incredibly important.

From my perspective, from the book's inception and my desire to participate in this, it very much feels like it's a group effort. It doesn't feel like it's mine. It feels like it belongs to everybody who worked on it and participated. I'm curious to hear, and I know this is an interview of me, but what do you feel? Why do you feel it's so important?

What continues to blow my mind is how, in 2024, we may believe we've come far, and we have in ways, yet we're still hungry for this kind of space where we can be fully ourselves and talk about what we truly want without labels and expectations. How we desire to engage in sex and our sexuality, whether it's with ourselves, one person, or many people, feels parallel to other aspects of life, which is something I wanted to explore with you. This book and topic feel like a microcosm of many things regarding women's liberation.

Yes! Yes. It unlocks something. On the one hand, people could look at it in a very narrow, myopic way and be shy, offended, or scared of even the conversation around fantasy. But it's not just about fantasy. It is ultimately about, as you say, liberation. How we ended up with the title was innocent. It wasn't manipulated. It came innocently, but it is everything. And this is being distilled to encourage women to look at what they want, not just under the covers, but from their lives, and what they want from other people in their lives. It's giving a voice to that. Sometimes, we don't realize we haven't necessarily identified that for ourselves. Or we may feel like we're emancipated and have full control and agency, but there are certain areas where we might feel so much shame. And the shame, as much as anything, might even be just about having a voice, about being heard, about asking for what we want, about all those myriad areas where we hold ourselves back for whatever reason—historically, generationally, within the circumstances in our workspace, or whatever it is.

The women who submitted letters for the book did so without attaching their names. With the obvious aside, what are some of the gifts that anonymity brought to this project?

There's something about women being encouraged to start with the cloak of anonymity and the freedom of anonymity to be able to expose themselves, lay it all out there, celebrate, and say, 'This is all of me.' And in absorbing that from other women who get to sit with these stories, it's become a cathartic feeling of identification and smashing through shame because they're reading some of the things they themselves feel and think. It's also incredibly empowering for women to feel like they are part of this community that is having this experience and part of this courage to ask difficult questions, take difficult next steps, and feel like it's time. This is a moment to shout, not to whisper, and that's evident everywhere. I see it in Kamala, I see it everywhere. From top to bottom, it's time to shout. It feels like a good moment for this conversation—and it's a big conversation not just contained in this book.

Shame is a giant part of this conversation, which you write about in your introduction. When you first read My Secret Garden, you were struck by all the shame. What else struck you when you read that, and what struck you while working on Want?

When I read My Secret Garden, I was struck by how contemporary some of the fantasies were. When I think of the 50s, I think of black and white, and when I think of the 60s and 70s, I think of things being in Technicolor, or at least sepia going into Technicolor. I do think about sexual liberation, too. But there was something about the details of some of the intimacy and the descriptions that I thought, oh wow, they had thoughts like that even back then, which is ridiculous because I was alive at that time. [Editor's note: Anderson was 5 when My Secret Garden came out.] But when I was reading it, I held both of those thoughts: how bold and wow, you could cut through the shame with a knife.

I had expected that shame wouldn't be so prevalent in our book. Because of the prevalence of sex around us everywhere and all the time—billboards and magazines and shows and podcasts and porn—I expected that we would have blasted through much of it. Or that it wouldn't be so heavy in our day-to-day experiences. And yet, there it was again, page after page. That made me sad on the one hand, and it made sense on the other hand. Yet, I have to imagine that part of the process of these women writing in and engaging in putting it on paper and releasing it into the unknown may have gone a small way toward releasing some of that shame. Certainly, having these conversations and putting them in the forefront does. And even just the act of asking oneself the question, Do I get what I want? Now, at this moment, am I getting what I actually really want?'

Depending on our history, shame can be ingrained in ourselves, in our DNA, in our genetics, I believe. And we sometimes carry shame in areas we don't necessarily need to. So perhaps in the process of having this conversation in a public forum, reading and absorbing these women's experiences, and identifying that we still struggle so much collectively to ask for what it is that we want, something might shift. Maybe by acknowledging that we can say, 'You know what, today, I'm going to take one small step towards not feeling shame… for my body, for my appearance, for my needs, my desires, my fantasies, my wish for things to be different. Today, I'm going to take a step towards asking for what it is that I really want.' And that can be anything. It can be minuscule or gigantic—and the minuscule can feel gigantic and sometimes have a monumental shift.

You contributed a letter to the book. How did that feel? Was it hard?

It was harder than I thought it would be! It was writing particular words. In a fantasy, everything's visual. It's all in pictures. So, suddenly being asked to put words to the pictures made it feel—and I'm going to say this, and it's an important word—dirtier. And it made it feel more illicit somehow. It veered into something that felt porn-like, even though, in my mind, it felt more innocent. And I realized that perhaps I have this misperception of how open or unfazed I am. Maybe I think that nothing surprises me, but at the end of the day, maybe a part of me is shyer than I had imagined. So, I did find it hard. It took a long time to write certain words and descriptives.

The book is out in the world on bestseller lists and in people's hands. How do you feel now that so many people are experiencing it?

I'm very good at compartmentalizing. So much of my compartmentalization comes from being a young mother and working crazy hours and splitting my brain into being 100 percent with my daughter and then 100 percent on set. Some of that is very useful today in putting 100 percent of myself into something work-wise and not being attached to the results. So often, as an actor, you work really hard on something, and then it never sees the light of day. Or you work on an accent for months, and then six people show up to the theater. So, this has continued to be part of how I operate. What I feel has been most meaningful to me are these conversations with women journalists, like yourself, who feed back real-time experience of it. Obviously, it's amazing to be on the New York Times bestseller list and lists in the UK. But at the end of the day, the real celebration is hearing women talk about their experiences and how empowered it is making them feel, not just in themselves, but in having this conversation and in a public forum so that it can spread to as many women as possible—hopefully around the world. I know that there will be places where, no doubt, it will be banned, and it will be too dangerous for women to read. But, just in terms of touching as many women as possible, I hope that it continues to spread.

And for men! I hadn't thought about men in this equation, which is a terrible thing to say because I was thinking of women, but what I've heard men say is great. Not just in terms of reading it to have a deeper understanding of what women want, which is great, but I've heard of men giving it to their daughters because of the bigger conversation and to counterbalance rising toxic masculinity. I'm very pleased that everybody is enjoying it and getting something from it.

You said earlier, 'This is a moment to shout, not to whisper.' What do you believe is women's most significant work, collectively, right now to help us all shout?

It's exactly that: It's to support each other. It's to amplify our voices. It's to be for and not against. There's enough trolling out there. There's enough against. There's enough hate. It is a time to be for other women, no matter what, and to look at the similarities and not the differences,

In the West, we have been the ones who have had the rights and the choice to shout the loudest, and we are at a moment when even our voices may be quashed. And if, in the West, our voices are quashed, then how can we be there to stand as the shoulders for those who don't have a voice at all? So, we're not just raising our voices for ourselves; we're taking advantage of this moment and raising our voices for women everywhere.

Gillian Anderson is an award-winning film, television, and theatre actor, and an activist and mother. In 2016 Anderson was appointed an honorary OBE (Order of the British Empire) for her services to drama. You can follow her @gilliana.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.