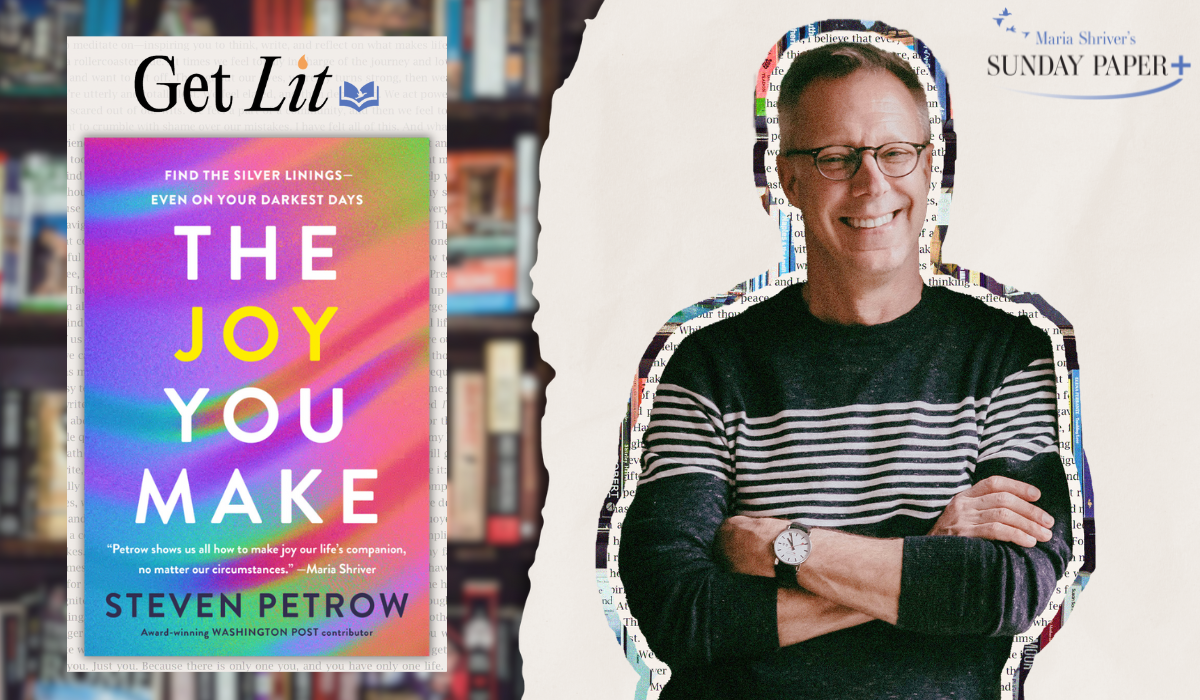

Get Lit with Steven Petrow: An Exclusive Excerpt from “The Joy You Make”

Who

Steven Petrow is an award-winning journalist and author who is best known for his Washington Post and New York Times essays on aging, health, and civility. Petrow is the author of six previous books, including the bestselling Stupid Things I Won’t Do When I Get Old.

What

In his new book, Petrow explores the many expressions of joy and shows readers how to find, cultivate, and share it. Combining his personal experiences with research and expert interviews, Petrow asks (and answers) the question: “What if there was a way to find the joy in everything?”

Why

Steven says he wrote this book for himself. “I had a really terrible year: my parents died within 100 days, my husband and I separated, and then my sister became ill with cancer. I started to implode and the world seemed very dark.”

“Then I remembered a quote that went like, ‘humans cannot live without joy.’ What I learned was that [joy] was about connection with other people, and that community and connection is the underpinning of joy. When we have those elements in place, we’re really primed to experience more joy in our lives.”

“I don’t think I’m alone in having felt this way. I think many of us are suffering. We’re in an epidemic of loneliness—so I’m hoping that this book will speak to many of us.”

& We

…chose Steven’s book as our first-ever Get Lit pick because in addition to being a beloved Open Field author, his message of hope and healing through joy is one we all need right now. Enjoy!

Here’s Your Exclusive Excerpt

A little consideration, a little thought for others, makes all the difference.

Eeyore

My mother died on a snowy evening in 2017, right after New Year’s. My dad passed away three months later. In between those two losses, my husband moved out of our house. Before the year had ended, my sister, Julie, had been diagnosed with stage four ovarian cancer. So I’m not overstating things to say that 2017 was a truly grievous year for my family and me.

Long before the events of 2017, I’ll admit I was already a glass-half-empty kind of guy, with a dark cloud hovering over me. (Some of my friends even call me Eeyore, the gloomy jackass in the Winnie-the-Pooh books.) I’ve also been called out as a curmudgeon, which is to say a midlife crank (long before I turned fifty) or a sourpuss. On top of that, I often felt as though my life was on autopilot. I was not fully engaged, unhappy for no particular reason. When I first read Angela Williams Gorrell’s book The Gravity of Joy, I felt a sense of connection and kinship, particularly when she wrote, “Many of us don’t sense joy. We don’t know how to become open to it, how to seek it, or how to share our longing for it. And often, even when it comes, we do not feel free to express it.”

Yet, with all this baggage, in the midst of the darkness of 2017, I surprised myself when I began to experience the tiniest sparks of joy. (Imagine that: me, Eeyore!) One afternoon, I spontaneously snapped a photo of a brilliant sunset, posting it on Instagram with the hashtags #gratitude and #beautyiseverywhere. Soon enough, I’d begun a regular practice of taking and posting photographs—of beauties like sun- and moonrises, flowers and fields, but also of a brick wall overlooking a parking area with humorous graffiti that read, “Bark here.” Each time, I enjoyed what I’ve now come to think of as a “joy hit.”

At first I thought my practice was just about taking pretty or amusing pictures. Then I believed it was about seeking and noting beauty in the everyday. Eventually, as more and more friends responded and began posting their own photos with the hashtag #gratitude, I understood that a big chunk of my joy came from sharing with others. I continued this practice throughout the pandemic, right up until now. The pictures never fail to delight me—to connect me with my friends, and they with me. Even though I didn’t realize it at the time, I had started my search for joy.

In my work as a journalist, essayist, and book author, I’ve long tried to extrapolate deeper life lessons from everyday experiences. With the pandemic winter of 2022 hitting us all hard, I decided to take a stab at better understanding joy, writing a column for The Washington Post titled simply enough, “How I found joy in life during difficult times.” The piece touched a nerve, quickly becoming one of the week’s most read stories. And why not? By that time we’d been locked in at home, shut out of the workplace, isolated and disconnected from friends and family for almost two years. More than a million Americans had died from Covid‑19. If that weren’t enough, the divides within families and communities had only deepened due to polarized opinions over mask and vaccine efficacy, climate change, and the 2020 election results. We had a mess on our hands.

Oh, and my sister fell out of remission that winter, leading to a new surge of uncertainty.

In the Post I wrote that “the past twenty-two months haven’t registered high on what I’d call the joy‑o‑meter,” which was an understatement for sure.

Poll after poll confirmed what many had experienced. One of them, a Kaiser Family Foundation study, reported that four in ten U.S. adults had experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression during the coronavirus pandemic, up from one in ten in 2019, with the most vulnerable among us—racial minorities, sexual minorities, the poor, older people, and younger people—at greatest risk.

Despite the overwhelming sadness and suffering many were experiencing, I also read a surprising poll published by the University of Michigan called “Joy and Stress during the COVID‑19 Pandemic.” It reported that 83 percent of adults over fifty had felt “some” or “a lot” of joy since March 2020, the official beginning of the pandemic. That statistic knocked me in the head, as it also did for one of the lead researchers, Jessica Finlay, a faculty fellow at the Institute of Behavioral Science at the University of Colorado Boulder. She acknowledged her surprise at the findings, explaining to me, “It’s not a monolithic story of decline or loss. People are finding silver linings in this time and are resilient to what they’re experiencing.”

And there it was. Joy is always present—in the silver lining, in the resiliency, in our memories, in the connection to those who share your grief when it comes. It’s in the everyday world, on good days as well as bad ones. You only have to look for it, be confident that it’s there, and be open to it when you find it.

I asked Finlay for some examples of joy in her life. She did not miss a beat: spending time outside, hearing birdsong in the morning, and most of all receiving a big hug from a family member after months of isolation. Listening to her, I began to see how these small joys sustained her, reminding me of my own practice of taking and posting photographs—also small joys that had buoyed me through my hardest year and beyond. I conducted an informal survey among Facebook friends, asking them, “How have you found joy in these difficult times?” The answers lifted me and, frankly, made me smile. Among the hundreds of responses, these caught my attention: adopting a hamster “who lives in a hamster mansion,” spending time with the grandchildren, streaming British comedies, eating chocolates, making a daily gratitude list, dancing, writing poetry, baking cookies, volunteering, cycling, enjoying the solitude, and—my favorite—reveling in “the unpredictability of autocorrect.” The deeper themes weren’t hard to see: connection, humor, helping others, gratitude, kindness, movement, and consuming lots of calories.

From THE JOY YOU MAKE by Steven Petrow, to be published on September 10, 2024 by The Open Field, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Steven Petrow.

If you'd like more from Steven, he recently sat down with fellow Open Field author, Martha Beck for a Sunday Paper PLUS exclusive conversation about using curiosity and creativity to find joy—even in tough times. You can find their conversation here.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.