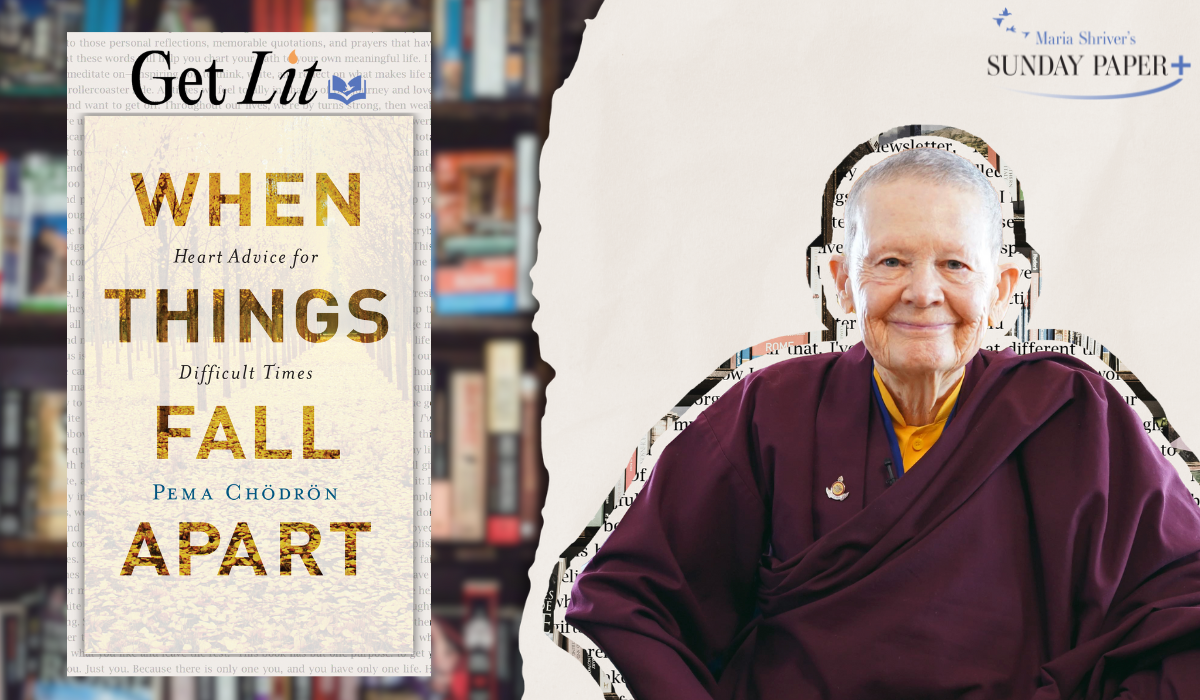

Get Lit with Pema Chödrön: An Excerpt from “When Things Fall Apart”

Who

Pema Chödrön is an American Buddhist nun and one of the most influential spiritual voices of our time. She is the author of numerous bestselling books including The Places That Scare You and Living Beautifully.

What

Here, in her most beloved and acclaimed work, Pema shows that moving toward painful situations and becoming intimate with them can open up our hearts in ways we never before imagined. She offers life-changing tools for transforming suffering and negative patterns into habitual ease and boundless joy.

Why

Pema Chödrön said of the enduring impact of this book, “As uncertainty and groundlessness increase, as we lose control of external circumstances, we find ourselves with our backs to the wall. One response is to cower in the corner, hoping that chaos and suffering will just go away. But in our heart of hearts we know that will never happen. The alternative is to use this opportunity to start waking up. Which is the more sane approach to our life?”

“If we do decide to start surrendering to our uncontrollable situation and letting go of resistance and resentment, we will have no shortage of opportunities to learn and grow. Our world, no matter how crazy and unreasonable it gets, will become our greatest teacher and ally.”

& We

…chose When Things Fall Apart as our Get Lit pick because it is a timeless manual for dealing with fear, anxiety, and pain. In a world filled with uncertainty, Chödrön’s guidance helps us see challenges as opportunities to grow and connect more meaningfully. Enjoy!

Here’s Your Excerpt

I had always thought of myself as a flexible, obliging person who was well liked by almost everyone. I’d been able to carry this illusion throughout most of my life. During my early years at the abbey, I discovered that I had been living in some kind of misunderstanding. It wasn’t that I didn’t have good qualities, it was just that I was not the ultimate golden girl. I had so much invested in that image of myself, and it just wasn’t holding together anymore. All my unfinished business was exposed vividly and accurately in living Technicolor, not only to myself, but to everyone else as well.

Everything that I had not been able to see about myself before was suddenly dramatized. As if that weren’t enough, others were free with their feedback about me and what I was doing. It was so painful that I wondered if I would ever be happy again. I felt that bombs were being dropped on me almost continuously, with self-deceptions exploding all around. In a place where there was so much practice and study going on, I could not get lost in trying to justify myself and blame others. That kind of exit was not available.

A teacher visited during this time, and I remember her saying to me, “When you have made good friends with yourself, your situation will be more friendly too.”

I had learned this lesson before, and I knew that it was the only way to go. I used to have a sign pinned up on my wall that read: “Only to the extent that we expose ourselves over and over to annihilation can that which is indestructible be found in us.” Somehow, even before I heard the Buddhist teachings, I knew that this was the spirit of true awakening. It was all about letting go of everything.

Nevertheless, when the bottom falls out and we can’t find anything to grasp, it hurts a lot. It’s like the Naropa Institute motto: “Love of the truth puts you on the spot.” We might have some romantic view of what that means, but when we are nailed with the truth, we suffer. We look in the bathroom mirror, and there we are with our pimples, our aging face, our lack of kindness, our aggression and timidity—all that stuff.

This is where tenderness comes in. When things are shaky and nothing is working, we might realize that we are on the verge of something. We might realize that this is a very vulnerable and tender place, and that tenderness can go either way. We can shut down and feel resentful or we can touch in on that throbbing quality. There is definitely something tender and throbbing about groundlessness.

It’s a kind of testing, the kind of testing that spiritual warriors need in order to awaken their hearts. Sometimes it’s because of illness or death that we find ourselves in this place. We experience a sense of loss—loss of our loved ones, loss of our youth, loss of our life.

I have a friend dying of AIDS. Before I was leaving for a trip, we were talking. He said, “I didn’t want this, and I hated this, and I was terrified of this. But it turns out that this illness has been my greatest gift.” He said, “Now every moment is so precious to me. All the people in my life are so precious to me. My whole life means so much to me.” Something had really changed, and he felt ready for his death. Something that was horrifying and scary had turned into a gift.

Things falling apart is a kind of testing and also a kind of healing. We think that the point is to pass the test or to overcome the problem, but the truth is that things don’t really get solved. They come together and they fall apart. Then they come together again and fall apart again. It’s just like that. The healing comes from letting there be room for all of this to happen: room for grief, for relief, for misery, for joy.

When we think that something is going to bring us pleasure, we don’t know what’s really going to happen. When we think something is going to give us misery, we don’t know. Letting there be room for not knowing is the most important thing of all. We try to do what we think is going to help. But we don’t know.

We never know if we’re going to fall flat or sit up tall. When there’s a big disappointment, we don’t know if that’s the end of the story. It may be just the beginning of a great adventure.

I read somewhere about a family who had only one son. They were very poor. This son was extremely precious to them, and the only thing that mattered to his family was that he bring them some financial support and prestige. Then he was thrown from a horse and crippled. It seemed like the end of their lives. Two weeks after that, the army came into the village and took away all the healthy, strong men to fight in the war, and this young man was allowed to stay behind and take care of his family.

Life is like that. We don’t know anything. We call something bad; we call it good. But really we just don’t know.

When things fall apart and we’re on the verge of we know not what, the test for each of us is to stay on that brink and not concretize. The spiritual journey is not about heaven and finally getting to a place that’s really swell. In fact, that way of looking at things is what keeps us miserable. Thinking that we can find some lasting pleasure and avoid pain is what in Buddhism is called samsara, a hopeless cycle that goes round and round endlessly and causes us to suffer greatly. The very first noble truth of the Buddha points out that suffering is inevitable for human beings as long as we believe that things last—that they don’t disintegrate, that they can be counted on to satisfy our hunger for security. From this point of view, the only time we ever know what’s really going on is when the rug’s been pulled out and we can’t find anywhere to land. We use these situations either to wake ourselves up or to put ourselves to sleep. Right now—in the very instant of groundlessness—is the seed of taking care of those who need our care and of discovering our goodness.

I remember so vividly a day in early spring when my whole reality gave out on me. Although it was before I had heard any Buddhist teachings, it was what some would call a genuine spiritual experience. It happened when my husband told me he was having an affair. We lived in northern New Mexico. I was standing in front of our adobe house drinking a cup of tea. I heard the car drive up and the door bang shut. Then he walked around the corner, and without warning he told me that he was having an affair and he wanted a divorce.

I remember the sky and how huge it was. I remember the sound of the river and the steam rising up from my tea. There was no time, no thought, there was nothing—just the light and a profound, limitless stillness. Then I regrouped and picked up a stone and threw it at him.

When anyone asks me how I got involved in Buddhism, I always say it was because I was so angry with my husband. The truth is that he saved my life. When that marriage fell apart, I tried hard—very, very hard—to go back to some kind of comfort, some kind of security, some kind of familiar resting place. Fortunately for me, I could never pull it off. Instinctively I knew that annihilation of my old dependent, clinging self was the only way to go. That’s when I pinned that sign up on my wall.

Life is a good teacher and a good friend. Things are always in transition, if we could only realize it. Nothing ever sums itself up in the way that we like to dream about. The off-center, in-between state is an ideal situation, a situation in which we don’t get caught and we can open our hearts and minds beyond limit. It’s a very tender, nonaggressive, open-ended state of affairs.

To stay with that shakiness—to stay with a broken heart, with a rumbling stomach, with the feeling of hopelessness and wanting to get revenge—that is the path of true awakening. Sticking with that uncertainty, getting the knack of relaxing in the midst of chaos, learning not to panic—this is the spiritual path. Getting the knack of catching ourselves, of gently and compassionately catching ourselves, is the path of the warrior. We catch ourselves one zillion times as once again, whether we like it or not, we harden into resentment, bitterness, righteous indignation—harden in any way, even into a sense of relief, a sense of inspiration.

From When Things Fall Apart © 1997 by Pema Chödrön. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com.

Discussion Questions: Think back to times of pain or upheaval in your life, did you come out of that experience different in any way? What changed?

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.