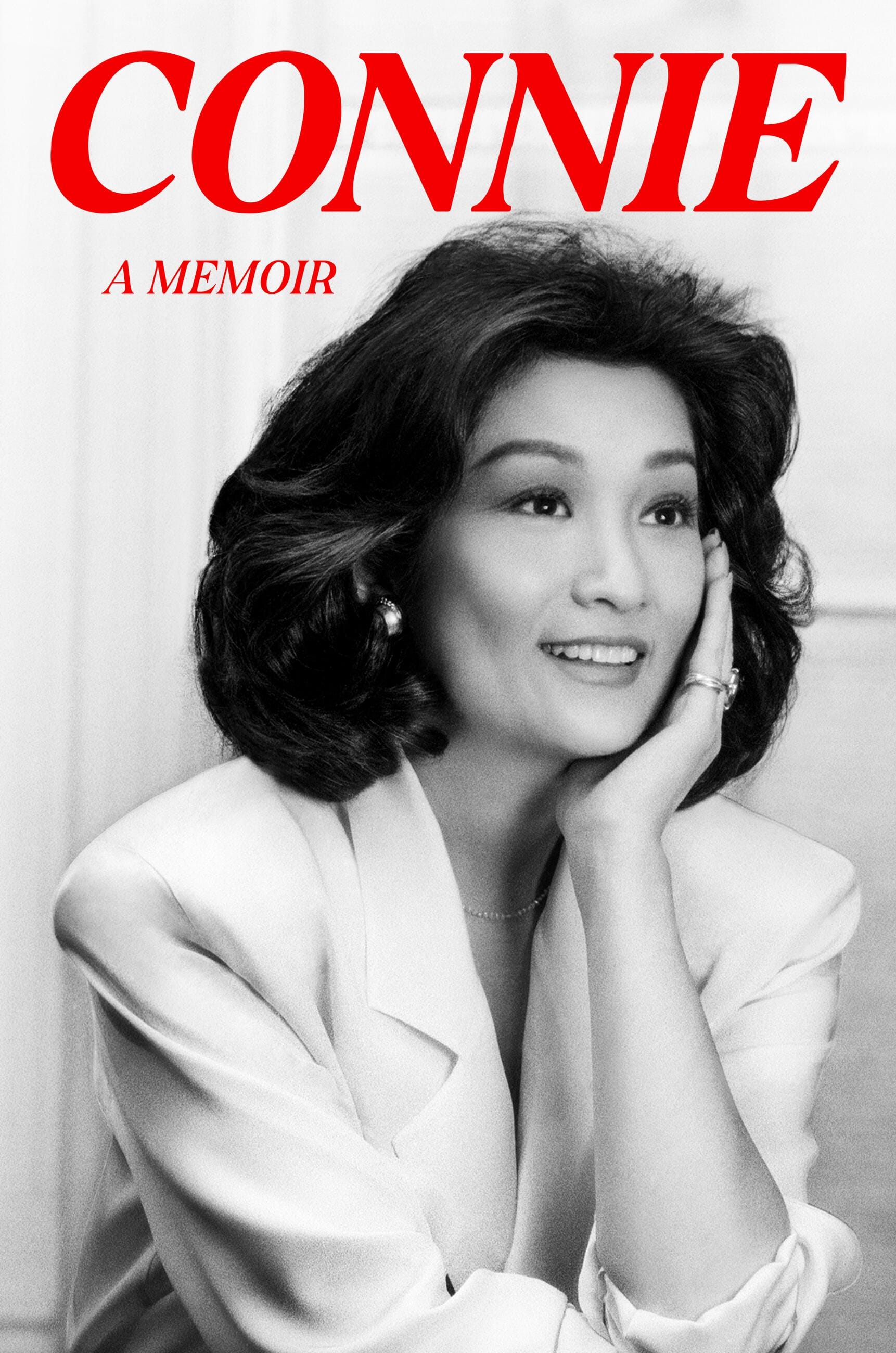

Get Lit with Connie Chung: An Exclusive Excerpt from “Connie: A Memoir”

Who

Connie Chung is a legendary journalist and trailblazer who made history as the first woman to co-anchor the CBS Evening News and the first Asian to anchor any news program in the U.S.

What

In this sharp and witty memoir, Chung provides a behind-the-scenes tour of her life and storied career. From showdowns with powerful men in and out of the newsroom to the stories behind some of her career-defining reporting and the unwavering support of her husband, Maury Povich, nothing is off-limits—good, bad, or ugly.

Why

Connie says she decided to write her memoir because, “I was flipping through my father’s old letters and realized that he was essentially assigning me a mission that was to carry the name Chung forward the way that sons do. Being a dutiful daughter who believed in filial piety, I made it my mission to become the son my parents never had. Then, I discovered a sisterhood of Connies named after me and thus, I decided I had a beginning and an end to my book and I was off to the races.”

“It’s my fervent hope that women realize we have come a long way but we have many more miles to go before we reach a level of parity, so we need to keep up the good fight.”

& We

…chose Connie’s memoir as our Get Lit pick because in addition to offering a never-before-seen look at her storied career in journalism, her reflections on life, love, and family offer wisdom to all. Enjoy!

Here’s Your Exclusive Excerpt

Chapter 1

Male Envy

I didn’t start out wanting to be a guy. But in the late 1960s, when I broke into the overwhelmingly male-dominated television news business, all I saw around me was a sea of white men. Bosses, colleagues in the newsroom, competing reporters, and even interview subjects were all the opposite sex. They were tall, wore identical staid suits and ties and wing-tipped shoes, and had deep, stentorian voices. I envied their bravado, their swagger, the way they could walk into a room and command it. When they spoke, it was with confidence and authority. They were entitled to respect because they were men.

I didn’t have close to their level of experience. I was twenty-three, wearing polyester, bell-bottoms, miniskirts, and shoulder-length hair, which I teased and sprayed into a flip. Since I stood only five feet, three and a half inches (don’t forget the half), I compensated by wearing stilettos. I wanted to be as close as I could be, eye to eye with the men. I did not want to look up at them. I wanted to be their equal. I tried to lower my voice to mimic theirs and copied their on-air cadence.

I knew they could easily bully me, and I was powerless to fight them, so I joined them. I knew I could never be one of the boys, but surely, I could adopt pages from their playbook. It was easy to imagine myself as just another white guy.

I became aggressive, tough, bawdy, and extremely competitive. Yes, I looked like a lotus blossom, but I talked like a sailor with a raw sense of humor.

Even though I had always been quiet and demure at home, I could not survive in the news business without being assertive, a fierce go-getter. The men were cocksure, so I mustered all the confidence I could to be the same. The guys thought they were made of the right stuff. By golly, I was too.

In fact, I had so thoroughly convinced myself that I was one of the white guys that when I walked past a mirror or a storefront window, I’d be startled to see a young Chinese woman staring back at me!

My four older sisters were shocked when I pursued a profession that required speaking before millions of viewers. “Our little Connie, who would not speak up, even when we asked her what she wanted to order at the drugstore lunch counter.” Growing up, those sisters were my own personal squad of helicopter moms— bossy and hormonal—who thought they knew better, always telling me what to do and what to say. The relentless cacophony of chattering voices was deafening. I never made a sound because I couldn’t get a word in edgewise.

But when we were all doing our chores, I would take the hose of a vacuum cleaner and “interview” people—anyone. The truth is, being a reporter fit perfectly with my personality. I preferred to observe, watching what unfolded before me, never expressing my opinion.

I morphed from the youngest of five sisters who had no voice at home, never uttered a peep at school, never raised a hand to answer a teacher’s question, into someone who was fearless, ambitious, driven, full of chutzpah and moxie, who spoke up to get what she wanted.

The problem was: men simply did not understand that I was one of them. They just didn’t get it. Many men in television news, especially those who became anchormen, contracted a disease: big-shot-itis. It was characterized by a swelling of the head, an inability to stop talking, self-aggrandizing behavior, narcissistic tendencies, unrelenting hubris, delusions of grandeur, and fantasies of sexual prowess. Very few women got the bug. If they did, they got milder cases. The disease created hurdles I had to either jump over or find a way around.

The desire to be a man came from a seed my father planted early in my career. He often typed letters to me on his manual typewriter, each beginning the same way: “My Darling Daughter, Connie.” It was his way of confiding in me while documenting his roots and ancestral history. I was in my early thirties, already in the news business, when I first read one of his letters in particular. He made a request of me, saying he had “wanted to be prominent and important, not only in the Chung family but in society, work and government.” But he never achieved that dream, so he assigned me an unusual mission: “Maybe you may like to carry on the name of Chung both in Chinese and English and tell how this Chinese family came to the USA.”

The reason this was such a strange assignment was that in China, as in many cultures, women were never expected to carry on their family names. In fact, we were expected to give up our last names when we married. Only males would automatically carry on the family name through generations. My parents had ten children, of which three were boys. But all three sons died as infants. I was the tenth child, the very last and the only one born in the US.

With no surviving males in the Chung family, I realized I could be the son my parents desperately wanted. I would find a way to carry on the family name Chung, to make our name memorable, a part of history. Wouldn’t it be the ultimate act of filial piety to honor my traditional Chinese parents and give them a son in me? It became my dream too, not just for them, but for myself.

Eventually my decision to be such an obedient, dutiful, and humble good girl to my parents and my bosses became a debilitating nightmare that I would not have been able to endure without my dear husband, Maury. More about that later.

Then a surprising twist. In 2019, a reporter named Connie Wang contacted me to tell me she’d discovered that an extraordinary number of Asian parents in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s had named their baby daughters Connie, after me! What? I’d had no idea my first name would be carried forward—to spawn a sisterhood of Connies. It may be difficult to believe, but I didn’t know I’d had such a profound impact on Asians. I was flabbergasted. And my head is still spinning.

It was a gigantic cherry on top of my cake. Here’s why. I could never declare success for myself. That’s probably a woman thing combined with a Chinese thing. I have always been proud to be Chinese, but at the same time, I knew we Asians were perceived by some as different, as foreigners, as second-class citizens. I was shocked that those Asian parents had seen me as someone who had broken the race barrier. Someone who was accepted. Someone whose name they wanted to carry on.

Throughout my career, I had striven for acceptance and equality and to be taken seriously, but I’d never assumed I had achieved any of those goals. Suddenly the Connie Generation declared success for me.

What a journey. I was bold, yet humble. I think that dichotomy was a Chinese thing. What a festival for shrinks!

As we say in television news, all that’s coming up. My family. My glorious highs and deep lows in the news business. My beloved husband, Maury. Our precious son, Matthew. The Connie Generation and so much more. Don’t go away.

Excerpted from CONNIE: A MEMOIR by Connie Chung. Copyright © 2024 by Connie Chung. Reprinted by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Discussion Question: Chung describes her transformation from a quiet, demure child to an assertive, competitive woman in the television news industry. What factors do you think contributed most to this transformation? Can you personally relate to the challenges faced by women striving for equality in professional spaces?

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.