Can We Truly Move Beyond the Vitriol to a Better Place? Former NIH Director Francis S. Collins Shows Us How

Francis S. Collins is a renowned geneticist and physician whose career has touched some of the most critical biomedical research of our time. Dr. Collins led the National Institutes of Health for 12 years under the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations, making him the longest-serving director appointed by a US President. Prior, he oversaw the world-renowned Human Genome Project, a 15-year-long undertaking to map and sequence human DNA.

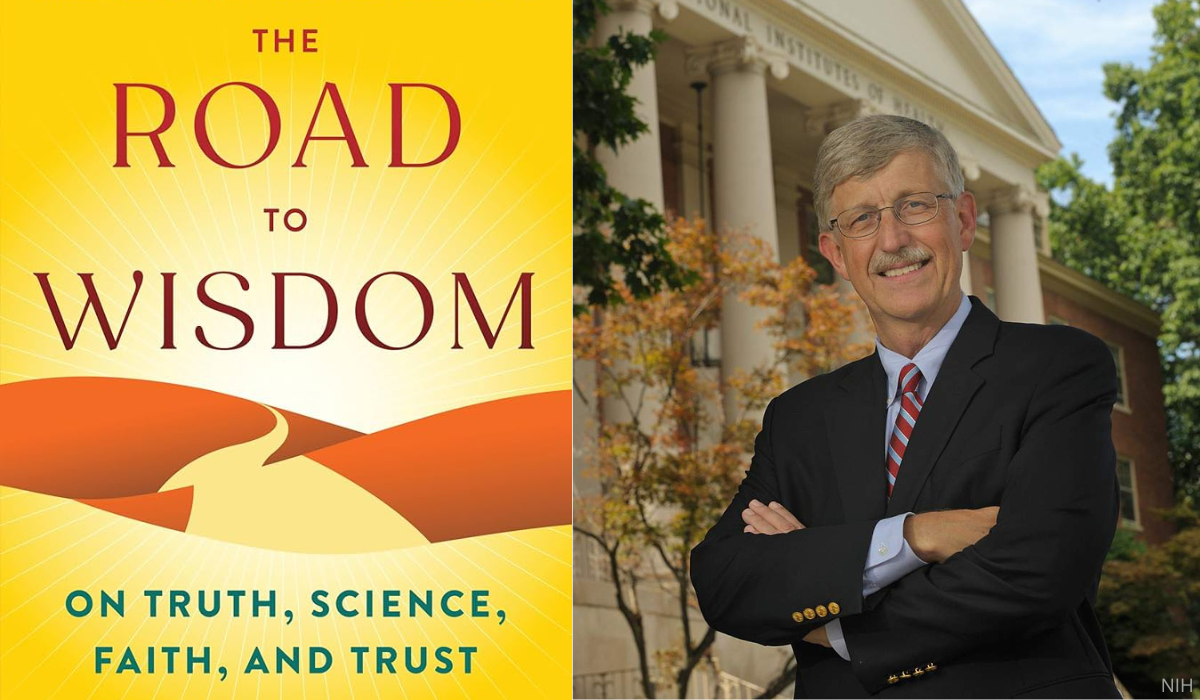

Dr. Collins, a Christian, is also a prolific author who has written extensively about his belief in science and faith and how a conviction in both can be concordant in this life. In his new book, The Road to Wisdom: On Truth, Science, Faith, and Trust, he dives into why these two things, along with truth and trust, are the critical pillars we need to heal and move forward from society's malaise of divisiveness and distrust. He sees how exhausted people are, yet he believes within us is a desire for healing and hope.

To help us find our way, he offers us a starting point for overcoming cynicism and, as he says, "getting back on that road to wisdom, where we all want to be."

A CONVERSATION WITH FRANCIS S. COLLINS

We are all facing many things today, which you write about: We're living in a culture of fear; there's a dwindling trust in science. What about humanity concerns you most right now?

We have lost critical anchors to our society's ability to work together and to have a productive future. One of those anchors is a recognition that there is such a thing as objective truth, and when that emerges, we all need to accept it and not just decide we don't like the conclusion and, therefore, we don't have to accept it. Part of that, of course, relates to science. Science is the way of learning the truth about nature, which is validated and confirmed reliable, and yet people's trust in science has been shrinking. There also is the truth that one derives from faith, a more transcendental truth—truths about love, grace, beauty, and goodness. I'm a person of faith. It seems that our faith communities have also been overtaken by a lot of the divisiveness and hyperpolarization that afflicts the rest of us. All of that then leads to a big confusion about who you trust and how you can take actions as individuals to try to put us back on a better course, a course that I call in the title of the book, The Road to Wisdom.

So, we've hit some potholes. Some of us feel like we're in the ditch. Still, for humans to flourish, we want to continue down that road to wisdom in a productive way that enables our society to become more of what we all want it to be: a place where you can disagree without being disagreeable.

You write a lot about disagreement and admitting defeat and missteps. You exemplify this in your book with the story of your time at Yale when you conducted your own molecular research for the first time and experienced a giant failure.

A total meltdown in my first project!

And later, you write about having intense conversations at Braver Angels, an organization you're part of that works to depolarize America, with a gentleman named Wilk who expressed viewpoints widely varied from yours. How does leaning into disagreement and owning our missteps provide us with opportunity?

That is part of what can get us back to a better place. Maybe it's a bit of humility that we all have to recognize that even though we feel very strongly about a particular position, we might not have all the facts. There's no better alternative to help us sort that out than meeting with somebody who doesn't agree with you and listening—really listening—to understand them. Braver Angels greatly influenced me, and I would encourage people to look around for their chapters. It's a great way to see how people with different views—political or faith— can understand each other. Wilk is a guy who runs a trucking company in Minnesota, and he was furious about the way in which the public health responses to Covid had done a lot of damage to his business and family, closing schools and so on. In my first conversation with him, it was pretty hard to listen to all that. Over time, I could see where he was coming from. It has helped me moderate some of my own positions about what was right and what was wrong, and we've become good friends. I would love to see more of that happening.

Wisdom is, of course, a critical topic in your book. You write, "It is not the same as knowledge, though it depends on it." What is wisdom, and why is it so important for us today?

Remember when Solomon was trying to figure out how he was going to be the new King, and he was feeling overwhelmed with responsibility? What did he ask for of God? It wasn't a fancy palace or a big army. He asked for wisdom.

Basically, wisdom does depend on knowledge, but it adds experience, judgment, common sense, and, most importantly, a moral foundation. Because knowledge often is sort of not attached to much in the way of ethics or morality, but wisdom has to be so. I guess you could make a silly analogy just in terms of science fiction characters: Think about Spock as the emblematic person of reason and knowledge. But then Yoda also has lots of knowledge and adds to that something else, which you might call wisdom.

Considering how tired and exhausted so many of us feel, you believe most of us still have a deep hunger for healing and hope. What is the first step to overcoming this exhaustion and cynicism and moving toward hope and empathy?

I have a lot of hope for our future. There are a lot of us, the majority of us, we've even been called "the exhausted majority," who are not endorsing all of this vitriol and polarization but are trying to figure out how to get us back on track. I think we can do that. So, in the book, I have a number of concrete steps to suggest to people. [These steps include] learning how to reach out to people who don't agree with you and listening and learning from them. It includes figuring out how to better manage your own inventory of what you consider to be established facts because sometimes things get smuggled in there, so that means learning how to filter incoming information and assess what you should consider reliable and what ought to be labeled with a bit of skepticism. We are barraged with incoming information, especially with social media. It's easy to get overwhelmed and even careless about accepting things, especially if they make you mad or fearful or come from somebody who's part of your in-group, but that doesn't always mean it's right. So, it's about doing a better job of sifting as a consumer of information.

I'm even suggesting that if we are serious about getting ourselves back on track, it would be good for people not just to say, 'Oh, that's nice,' but to make a commitment. I have included a possible pledge in the book that I would ask people to consider taking. We do this when it's an important issue, such as getting married, or when I went to college, I pledged to follow the Honor Code. That was an important moment. So why not pledge now that we're going to stop being part of the problem and start being part of the solution? The pledge basically includes loving your neighbor, refusing to demonize people who don't agree with you, reaching out to try to understand people, and doing a better job of assessing what is really true and not denying things that are true just because you don't like them. If people are interested, that pledge is a good place to start. It is in the book and also posted on the Braver Angels website.

Lastly, considering how much you have juggled and continue to do, what helps you to nourish your compassion and rise above the noise in your daily life?

I am up most mornings at 4:30 or 5, and the first thing I do is to try to get re-anchored to my faith by reading the Bible or perhaps a book of devotions and reflecting a bit on that. If I get started that way, it's easier not to get knocked off my course by something that comes at me a couple of hours later. I am also fortunate to have other believers around me who I am close friends with and can reach out to if I'm having a tough dilemma and seek their advice and prayer. One doesn't want to be a loner in a circumstance like this; you need other like-minded people around you. A lot of us have become more isolated than ever. And that's another thing we can do: Try to break down those boundaries and not depend on text messages to link us up with people but actually try to fill those friendships in a more vigorous way.

Francis S. Collins, MD, Ph.D is a physician and geneticist whose work has led to discovering the cause of cystic fibrosis, among other diseases. In 1993, he was appointed director of the Human Genome Project. He served three Presidents as the Director of the National Institutes of Health.

Want to sign The Road to Wisdom Pledge? If so, you can find it here.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.