Why Dr. Anthony Fauci Chose Public Service—Despite the Hurdles

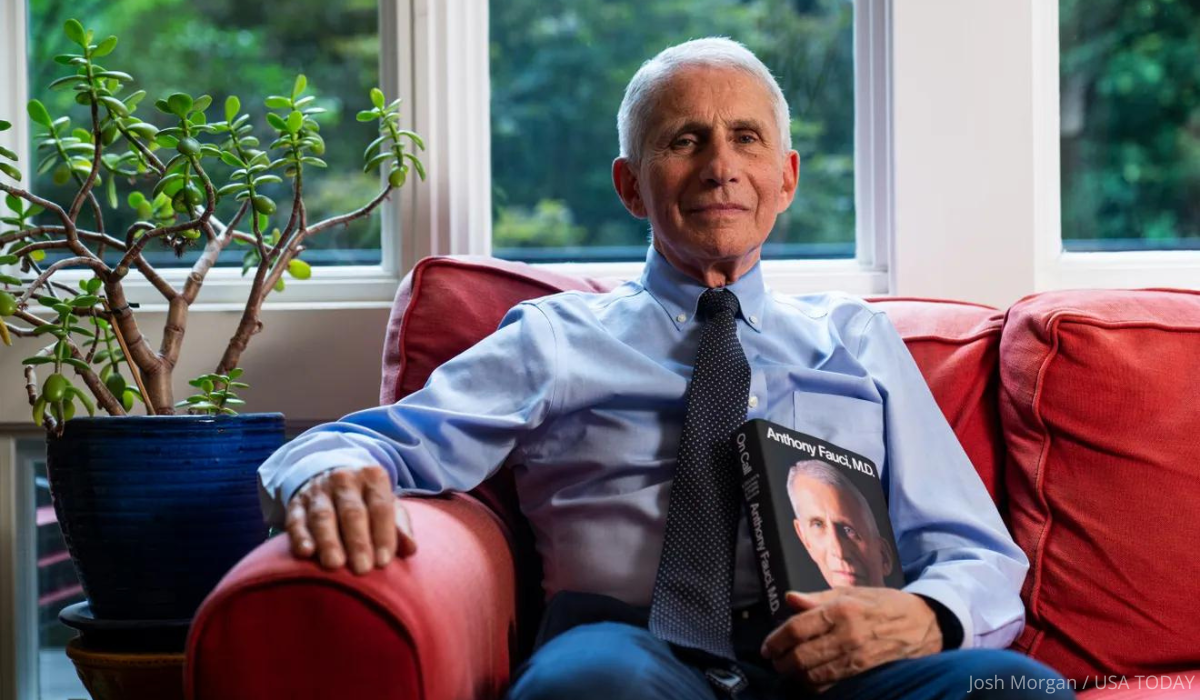

My story is about what it means to devote one’s life to public service.

It has not always been an easy life. It comes with long hours, missing out on personal and family time, an enormous burden of responsibility, and considerable anxiety and stress and, at times, opposition and even hostility. It often requires putting aside personal fears to fulfill one’s mandate, and it demands rising to occasions that others might choose to avoid. But it can be a deeply purposeful and rewarding experience, one that centers on taking care of people and working toward the common good.

“Beyond my control, I became a symbol of the profound divisiveness in our country.”

My parents instilled in me a conviction that helping others could be a meaningful way of life. This conviction was strengthened during my years in high school and college under the Jesuit priests whose mantra is service to others. In my case, the vehicle for this has always been science and medicine. Yet when I first came to Washington, D.C., from New York City as a fellow at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, I did not know that this calling would take me where it has: to the very center of the catastrophic AIDS epidemic; to helping protect the country from potential bioterrorism threats such as anthrax and smallpox; to combating outbreaks such as influenza, measles, Ebola, and Zika; and of course to contending with the COVID-19 pandemic. My career placed me at the center of where I confronted death all around me. These crises also allowed me to participate in and occasionally contribute to breakthroughs that saved countless lives.

Nor could I predict that I would work with so many White House occupants, Republicans and Democrats; testify before Congress hundreds of times; and forge lasting friendships with people of different nationalities and political beliefs. And after a career of remaining determinedly nonpolitical, I certainly could not anticipate that I would become a political lightning rod—a figure who represents hope to so many and evil to some. Beyond my control, I became a symbol of the profound divisiveness in our country.

This brings me to the issue of my now being one of the most recognizable people in the country. The positive aspect of this is that I can touch so many people in a way that helps to preserve or improve their health. But it is one thing to go on TV and deliver public health messages to millions of people where I need only to look into a camera and my impact can be felt. It is an entirely different feeling to walk down the street or into a restaurant or the post office and have most people know who I am. It is this complete loss of privacy for someone who is fundamentally a private person that can be unnerving. This is one of the many ways that COVID has affected me and my family.

As I write this in the winter of 2024, COVID still lingers among us. This disease will not be eradicated and is not likely to be eliminated from certain geographic areas. But we can all see that the dire situation that gripped the nation and the world beginning in the winter of 2020 is behind us. Thanks to vaccines and treatments, most of us are going about our lives as we did before COVID. While I recognize with a heavy heart the cost of the pandemic in terms of lives lost, ongoing health concerns for those with long COVID, and the economic and social upheaval so many people experienced, I am deeply grateful for the scientific and public health progress we have made.

Still, as exceptional and even unique as COVID and this period in our collective history seem to us, unfortunately it was not. The entire history of humanity has been marked by plagues and devastation, and new pandemics will certainly emerge in the future. This is why it is so critical to prepare for the unpredictable, or, as I have often said, expect the unexpected.

At times, I am deeply disturbed about the state of our society. But it is not so much about an impending public health disaster. It is about the crisis of truth in my country and to some extent throughout the world, which has the potential to make these disasters so much worse. We are living in an era in which information that is patently untrue gets repeated enough times that it becomes part of our everyday dialogue and starts to sound true and in a time in which lies are normalized and people invent their own set of facts. We have seen complete fabrications become some people’s accepted reality.

This is not a new paradigm. Propaganda—turning words and ideas into weapons—no doubt started thousands of years ago, and we have seen it used to devastating effect many times within the life span of this country as well as over the course of world history. We have seen how easy it is to undermine the foundations of our democracy and of the social order. What is new is the dizzying pace at which information gets disseminated and amplified on the internet and through social media, disorienting and dividing us as a nation.

These divisions did not come out of nowhere, and they will not go away overnight, because they are set in the minds of so many people. It is why I am putting my hope in the young people I encounter around the country and the world.

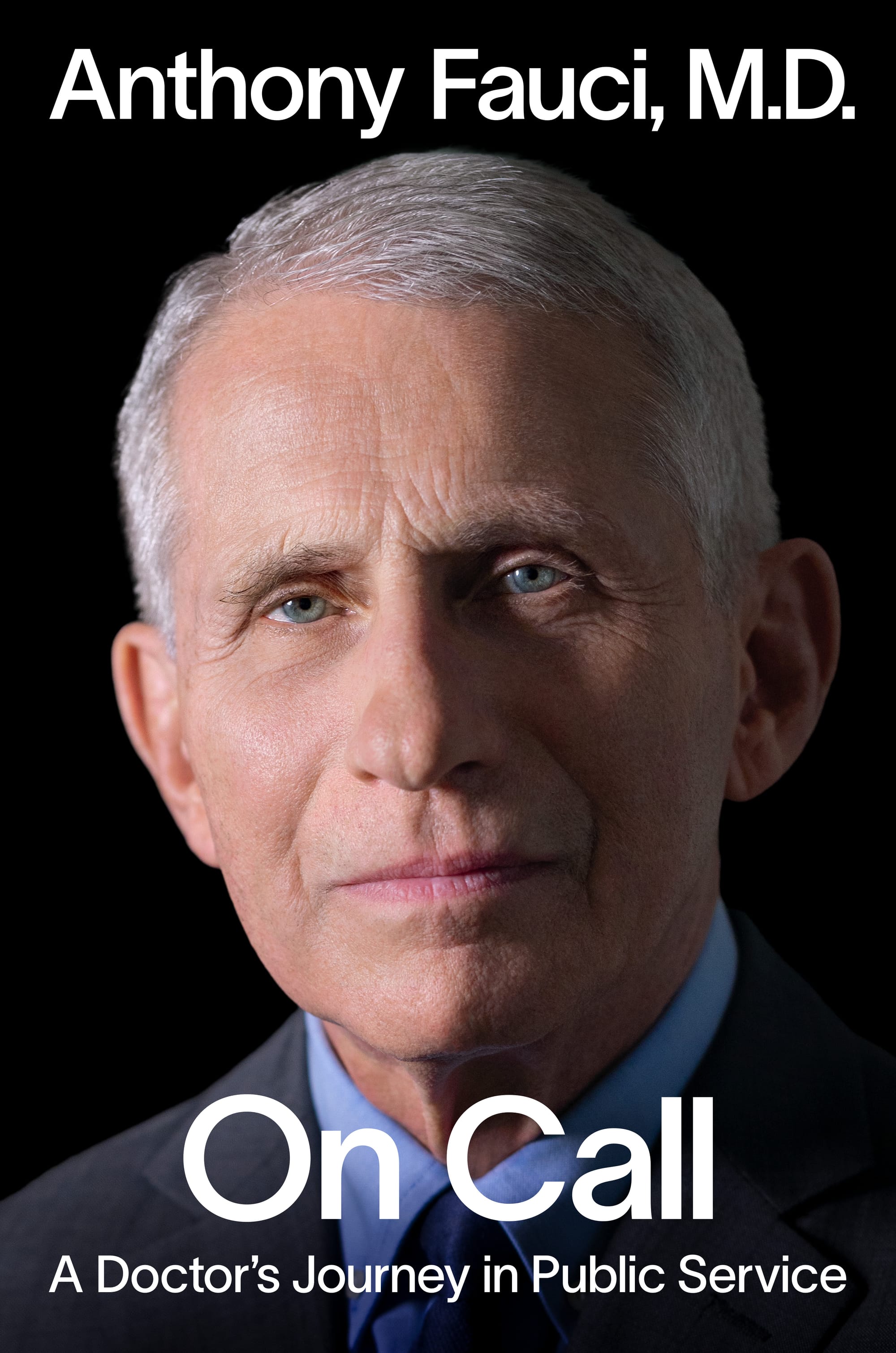

Which brings me to the next chapter in my life. When I decided to step down from my position as director of NIAID, I asked myself what I could do over the next few years while I am still filled with passion and energy and blessed with good health. The answer came to me quickly and clearly: to share my experiences with the world and particularly the younger generation where I might serve as an example and hopefully an inspiration for some to pursue a life serving others not only in the field of medicine and science but in any of a number of career paths that one might choose. This was my main motivation in writing this memoir.

“These divisions did not come out of nowhere, and they will not go away overnight, because they are set in the minds of so many people.”

It was also the reason I was delighted to accept the offer of Georgetown’s president, Jack DeGioia, to become a Distinguished University Professor at the School of Medicine and the McCourt School of Public Policy, where I can have daily contact with the bright and inquisitive minds on the Georgetown campus.

In the year since I stepped down as NIAID director, I have had the opportunity to lecture and engage in fireside chats and moderated discussions throughout the country. What became even more clear to me was something I already knew: that the diversity in our country in its myriad forms—geographic, economic, cultural, racial, ethnic, and political—makes us an attractive and great country. It is when this diversity gives way to divisiveness that society suffers.

I have always been a cautious optimist, and I hope that the better angels in all of us, who tell us that we are more alike than different, will prevail and lead to a spirit of civility and respect for each other.

Excerpted with permission from ON CALL by Anthony Fauci, M.D., published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Anthony S. Fauci.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.