White House Chef Andre Rush Appeared to Have It All Together—but He Was Crumbling on the Inside. If You Are Too, Read On

Chef Andre Rush has an endless depth of empathy. As he chats with me over Zoom, there’s no pursuit of small talk, no forced banter. Rush, or “Chef,” is forthcoming. Warm. He and I are meeting to discuss his book, Call Me Chef, Damnit: A Veteran’s Journal from the Rural South to the White House, but it’s not a contrived journalist-talent-book-tour conversation. Rush, a retired Master Sergeant of the US Army, celebrity and former White House chef, and founder of mental health non-profits, is here to get real about the tough topics he covers in his book: PTSD, trauma, suicide, toxic leadership, racism. “People instantly tense up,” he says about the topic of racism. “Or if I say ‘whiteness,’ people will say, ‘But you're Black, so what are you going to say about it?’ But I say, ‘Listen to my words. Listen to my actions.’”

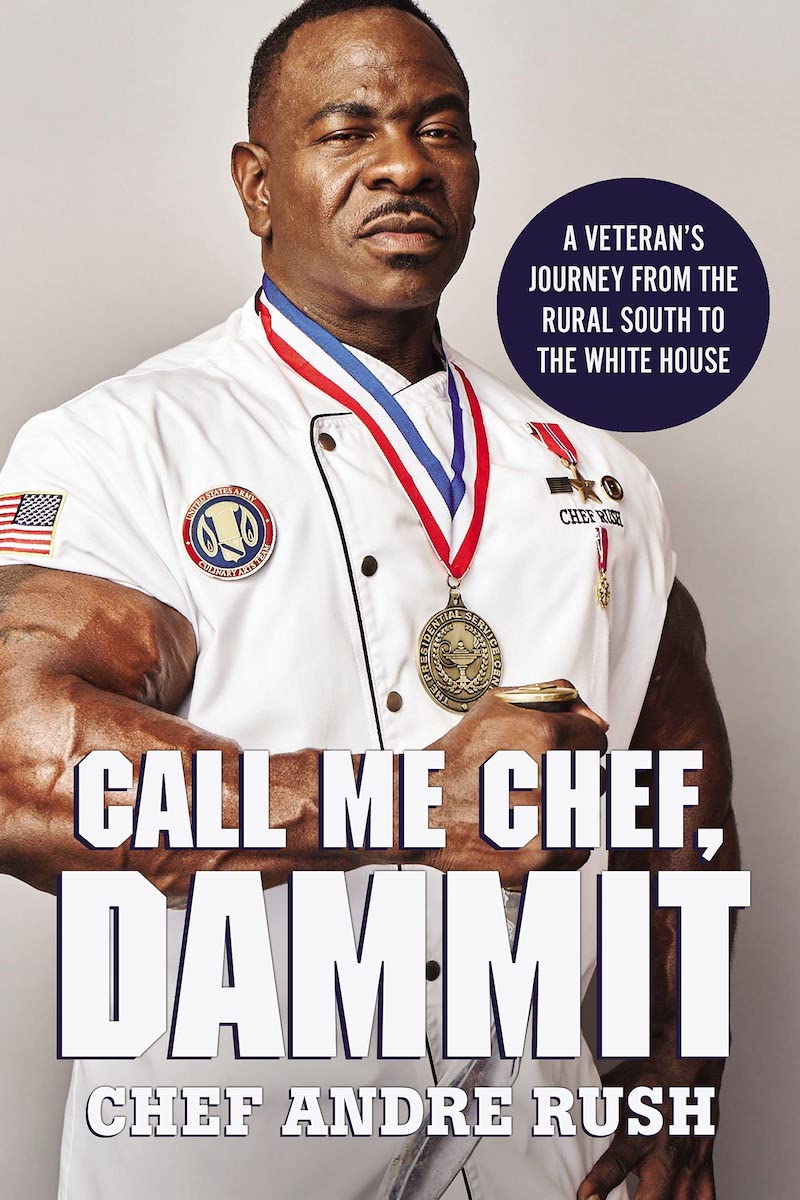

Some of the words and actions Rush hopes people hear the loudest are around mental health and how it’s an issue that impacts everyone—including him. A notably fit man with 24-inch biceps (he’s garnered a following for his thousands of daily push-ups), Rush says people are quick to think his strength precludes him from suffering. It’s the opposite, he says. “My mother taught me to love, my dad taught me to work, but they both taught me to understand that you don't ever judge a book by its cover.”

Call Me Chef, Damnit takes you through Rush’s upbringing in rural Mississippi, to his 24 years in the military, all the way through to the four presidencies during which he cooked in The White House. (Chef was working at the Pentagon during the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which led to his suffering from PTSD.) This book, he says, has been a way for him to share what brought him down and picked him up. “I almost didn't write it being in politics and in the military […] but I decided I wanted to tell what I wanted to tell, even with the backlash. These are the things that make people uncomfortable—but there’s no reason for you to feel uncomfortable because this is an open conversation and it’s about understanding.”

A Conversation with Chef Andre Rush

You’re a retired Master Sergeant of the US Army. You're a celebrated chef who worked in the White House for four administrations. You're a published author. And you’re an advocate for mental health awareness. Considering all that you’ve done, what would you say to your younger self growing up in the rural south?

I'll be very honest with you. I would say do more for yourself. More self-care. My life has always been a life of servitude. I use the word ‘servitude’ because my father was a preacher. My sister's a Colonel in the Air Force. My brother was a military officer in the Navy. My other brother is a Merchant Marine. My other sister is a teacher. We all did a lot. I did a lot, and I do even more now, for so many people and I don't regret it whatsoever. But at the same time, I know that I had to stop a lot of things for myself to help more people. Now I realize I could have helped even more people by taking better care of myself. So when I say self-care I mean taking care of myself to then take care of others.

Mental health is an important topic for you. There’s still a stigma around talking about mental health issues, particularly among men. How can we overcome this?

We need to talk about mental health—in general—more. For men, women, and kids. There is this huge stigma. I am a big masculine guy, so people receive me differently. When I first came out [with PTSD], people didn't think that anything could be wrong with me. They didn’t think anything could break me, or that anything emotionally was going on. But inside me I was saying, you need to take care of yourself, not them.

A lot of this work starts with leadership, especially in the military. When I was in the military and I asked for help, they asked me, ‘Do you like your job?’ And I thought I got this. Let me keep going. I can drive. I'm big enough. I'm strong enough. They're telling me that I am, so I'm telling myself that I am. But that's that self-care part again. It was a ticking time bomb for me inside.

For anyone struggling or who knows someone struggling, what do you want them to know?

When I came out and said, ‘Hey, this is what is happening with me,’ I had tens of thousands of people follow behind me. They flooded me with thanks. Kids, women, alpha males, alpha females, big guys… They said, ‘This is what I needed. I'm glad to know I'm not alone. I'm glad this is not just me.’ This was [from people] in the military space and people in general. Mental health issues don’t have to be trauma from war. They can be from a boss or from a past relationship or from anything.

So I tell people to be open to it. But I also tell the people on the outside looking in to understand that if someone comes to you, you need to pay attention. If they say something to you, it's a cry for help or support. You need to be that person. [It doesn’t matter if this cry comes from] a big guy, [or from someone who’s] smart and educated or has all this money. That doesn’t matter. Mental wellness doesn't have a rank. It doesn't have a color. It doesn't have a monetary value. It's just there—100 percent.

You start your book off by writing ‘don't judge a book by its cover.’ And we do that so often. We put each other in boxes. We put ourselves in boxes. And as you said, people look at you, a big masculine man, and think, Chef, you’re fine, you’re tough, you’re okay… But that vulnerability part and breaking that ice is everything.

You’re so right. That’s what happened. I get it a lot. I get it even now, even saying the things I say. People will be like, ‘Wow, you have this problem?’ Yeah, I'm human. We're all human.

You spent 24 years in the military and followed that by working as a chef in The White House for four presidencies. During this time, how has cooking been a vehicle of connection?

Cooking has been my coping tool. It combated all the triggers so much so that I started this group when I was in the military called Cooking to Cope. Cooking saved my life. I don’t cook just to cook and to learn some recipes. I cook because I want you to appreciate the food. I want you to understand that food is holistic medication, happiness, love relationships, being together, humility, all these things. Food is more than what we just think of as consumption. It helps your body to grow and helps you to combat disease. And it’s a lifestyle. So it started off as a coping tool for me, then it turned into a lifestyle.

There’s also a theme of decency in your book. What can we each do today to take care of each other and to move humanity forward?

The first thing is to take care of yourself. You need to take care of yourself to take care of others. As I said, I sacrificed a lot and I say this because you must have your mental health first. You can't say you're going to do a mission if you don't have a mission for yourself first. So take care of you.

Then, give thanks and gratitude. You can start by simply saying hello to or smiling at someone. I'm a big guy and people may look at me and be intimidated, but when I smile, people light up. That’s my fuel.

It all starts with your foundation—and then you grow from there. I started my nonprofit to give back to other nonprofits. And it's not about me. It's about everyone helping each other. We can all build each other. That's what it's all about. It's a community base.

Lastly Chef, how many push-ups are you doing each day, for real?

I am doing 2,222 pushups a day minimum, except for Saturday and Sunday. I eat a lot on Saturdays and Sundays! I also do my side challenges with people. But my pushups are for the 22 veterans a day who commit suicide—plus with mental health awareness and bullying […] This is all a big part of my cause.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.