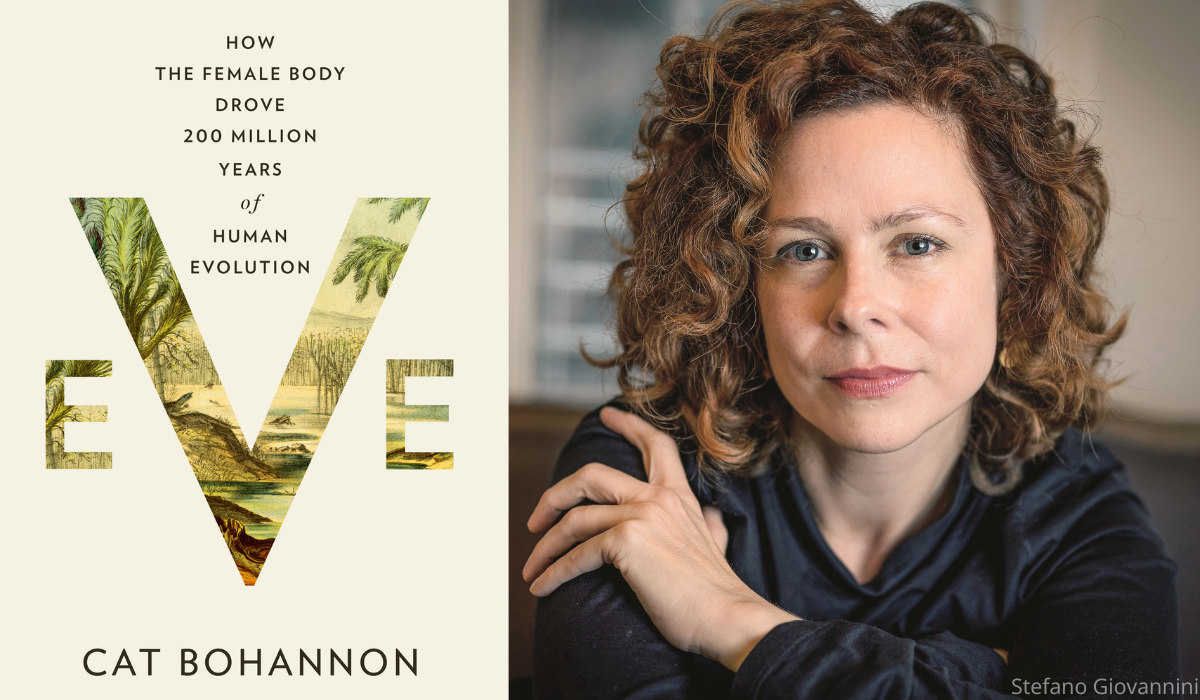

Cat Bohannon’s Bestselling Book Puts Women at the Center of Evolution. Here’s How it Can Help All of Us Get Healthier

In recent years, women’s health issues have gotten more airtime than ever before.

We know women suffer disproportionately from many diseases, like Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, and autoimmune conditions. We know women make up 85 percent of migraine patients, and are twice as likely to have depression. Most of us have at least heard that heart attack symptoms present much differently in women than in men, and that the menopausal hormone therapy we were taught to fear for so many years can actually be incredibly protective when it comes to our health.

Yet we don’t know why.

In her best-selling book, Eve, Cat Bohannon sets out to answer some of these questions scientists should’ve been addressing for decades—but didn’t.

This week, The Sunday Paper sat down with Bohannon to talk about why she spent the last decade trying to understand how women’s bodies came to be so different from men’s, how these differences impact our health, and why all of us—men included—should care.

A CONVERSATION WITH CAT BOHANNON, PHD

Why is tracing the evolution of women’s bodies necessary when it comes to helping us understand our bodies and how they work today?

It is literally true that our bodies are things that have been evolving for hundreds of millions of years.

Astrophysicists like Neil deGrasse Tyson like to say things like, “You’re made of star stuff.” And we get all sparkly eyed when we hear that. I’m like, “Yeah, but you’re also made of this little weasel beast from under the feet of dinosaurs 200 million years ago—a little more recently than the star stuff.”

And very importantly, all of the challenges that our ancestors—our Eves—faced are still playing out in our bodies today. So if we want to wrap our heads around why so many more people with female bodies have autoimmune diseases of all nearly all types, for example, well then you probably need to think about the fact that we’re mammals and that the placenta naturally down regulates the maternal immune system when you’re pregnant. And then you need to ask, “How does the body compensate for that? How do we build a body that can survive something like that, and not immediately die of infection as soon as we’re pregnant?” It’s probably the case that the female body in general has a slightly different immune system—a different pattern of inflammatory response.

Which is to say there are very few things in medicine today that don’t have an evolutionary feature. We have to take evolution into account because that means we can find better directions to reduce the suffering of women and girls. And then in addition, the suffering of people with male bodies.

For many years, there was a “male norm” in medical research. Is science doing enough now to make up for all that lost time?

The female body is radically under studied and radically under cared for. And that’s true not just in us, but it turns out to be true all the way down to rats in the lab.

Whenever we’re doing a biological study, it continues to be the case that we’re far more likely to use only males as our subject pool. The literal way in which we build our understanding of how bodies work in general, in mammals, is coming from male bodies—unless we’re specifically asking for something about the ovaries, the uterus, or lactation. Then we’re like, “Okay, fine. I guess the chicks can come.”

This has obvious implications, because where does biomedical research come from? It comes from basic biology. Long before you ever arrive at something like a target drug or a new treatment for disease, we’re building on how we understand our bodies work in general, from basic research. That means by the time you arrive at human clinical trials, it may not have been tested on female bodies at all. And for a very, very long time that was true.

We’re trying so hard across the biological sciences and the medical fields to catch up—to fill this massive gap in our understanding of how our bodies work and how medicine might interact with those bodies and where sex matters and where it doesn’t. I think that there are a lot of really good actors in this space.

But I also think it’s really important to keep our foot on the pedal, because there’s just so much of a gap to fill. We have to keep reminding ourselves that what has been done is not sufficient. There’s so much more to do.

So many women feel they get the brush-off from their doctors because they don’t have the language to talk about their bodies. Why is it so needed for women to have more accurate health information?

One of the reasons it’s so important is because the body is already taboo, especially the female body. I mean, the majority of our swear words in the English language are deeply tied to either a part of the body or something we do with it, very often leaning towards the female side of things. That means a lot of knowledge about these actual bodies we live in automatically feels weird, loaded—forbidden even. There’s a deeply embedded storying that we do about our bodies and what we are and aren’t allowed to know or think about them—and when we are and aren’t allowed to seek care.

There were two reasons I thought it was so necessary to write this book. One is simply because anytime you can open that door and make it okay to talk about what it’s been like to live in these bodies, that’s good work. But it’s also because there’s been so much new research, finally, into the female body and sex differences shaping our understanding of all bodies. In some ways, this book, as big as it is, is kind of a starter manual. I hope that it gets improved on because that’s how fast things are going.

Why should men care about your book? How does understanding sex differences help all bodies, not just the under-studied female body?

You would think that we know so much about the male body, given male bias in biomedical research and in biology. But actually, not really—because that’s not exactly how mammals work. We know that many mammalian species have females living longer than males. And it doesn’t just seem to be about behavior. It seems to be deeply something about the immune system and the cardiovascular system and how sex hormones interact with those systems. It has to do with cellular repair—we’re talking about the actual gear works of what it is to be alive—and sex differences in some of that. We’re still trying to tease apart what that is. And until we properly study the biology of sex differences, we’re not really modeling how it’s all working.

What’s really been interesting to me is how many cis men are in my signing lines on my book tour. What most of the guys want to talk about is their physical vulnerability. There’s this thing where masculinity is supposed to be invulnerability, and so men don’t know who the hell to talk to about their weird prostates. So again, you open that door, and then people can walk through it.

Not only can men who read my book know more about half of the planet—which is, on the face of it, a useful thing—and have a better story for where our species comes from. But there’s also a surprising amount about male bodies in this book, which they can then take on board and see what jives with their own understanding of their bodies and what doesn’t. And hopefully that also gives men permission to talk about their bodies with others in a way that’s less fraught.

Cat Bohannon completed her PhD in 2022 at Columbia University, where she studied the evolution of narrative and cognition. Her writing has appeared in Scientific American, Science, and more. Eve: How The Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution is her first book.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.