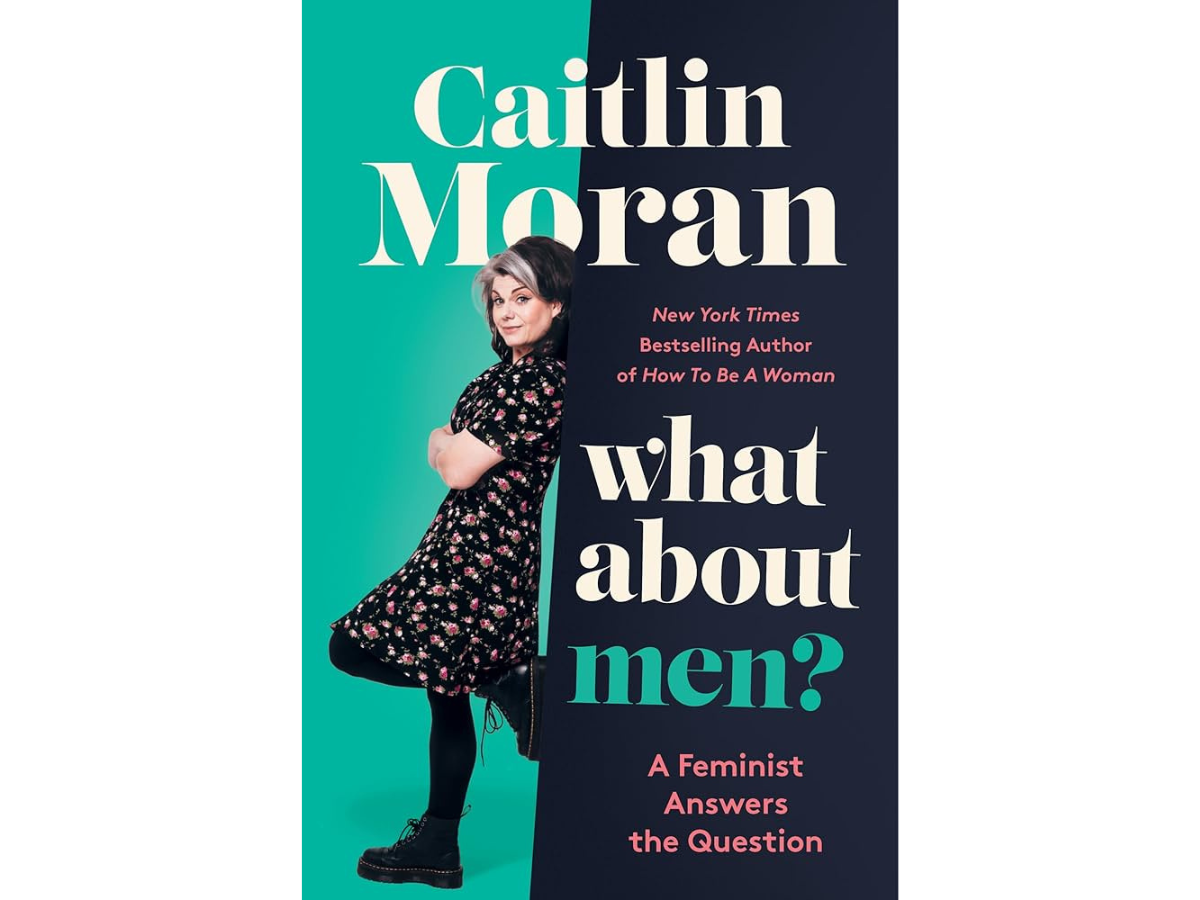

To Build a Better World for Women, Bestselling Author Caitlin Moran Says We Must Also Ask: What About Men?

Caitlin Moran is one of the most prolific feminist writers today. The British journalist has penned numerous books igniting continued social change, including the bestsellers How to Be a Woman and How to Build a Girl. So why is this outspoken, passionate women's advocate now writing about… men?

We ask this of Moran, who just released her newest book, What About Men: A Feminist Answers the Question. It is widely common wisdom that women have faced—and continue to face—uphill journeys in the fight for equality. But Moran argues that men suffer too and have been for a while. Her focus isn't on one group having power over the other. It's about compassion, equality, and making the world better for everyone.

"I had genuinely not understood why a man hadn't written a book like this," she tells us. "I thought it seemed obvious that you would write a book that was mainstream, accessible, funny, that covered the whole of a man's life. But on the first night [talking about the book], someone in the audience said, 'I can tell you why: Can you imagine if a man, particularly a straight white man, wrote a book called What about Men?'

And then I got it,” Moran continues. “It had to be a woman and a known feminist to start that conversation."

A CONVERSATION WITH CAITLIN MORAN

For years, you've fielded questions from people about how to help boys and men. You write that you had "become massively irritated about men stomping all over a women's thing, shouting, "WHAT ABOUT US?" Then something started to shift for you, and you began to really care and see the need for all of us to care. What sparked this?

The inciting incident was on International Women's Day [in 2019]. I'd gone to talk to a group of 15- and 16-year-old boys and girls about women. But I found that the boys were unreceptive and, indeed, they were angry and hostile. As they saw it, we talked about women all the time, and they were thinking, Where's International Men's Day? Of course, it is November 19th, but men seem not to know that because women are better at organizing these things. One of the things I float in the book is that we need to do more on International Men's Day. Men need to feel empowered to talk about their problems like we do on International Women's Day.

So that day, there were angry young boys, and I couldn't work out why the boys were so angry. Generally, I find people are angry because they're scared, and anger is just the boil. But how could boys be scared that women were winning when, by any measurable index, we're not? Still, one in four of us will be sexually assaulted or raped, the pay gap still exists, the world leaders of the UN are majority male, men continue to lead in business and economically, and places such as Afghanistan exist where women are not treated as humans, and that there is no country where men are ruled over by women. So, given all of those facts. The only thing I could think we've got that they don't have is feminism. Women talk about our problems. We have this sisterhood, a network. It's not perfect. The sisterhood can turn on itself, but a teenage girl with a problem who may not be fortunate enough to have parents or people to help her can go online and find movies, books, and TikToks that will give her advice. And there just isn't that for young men.

It's wild to think about because the fight for a progressive, equitable, kinder world is in full swing. What concerns you most about this issue?

Generationally, I think it's gotten worse because at the point of this recent wave of feminism, the fifth wave that started around about 2010, I observed that the liberal left-wing men went, 'Okay, the women are having a moment, and we're not now going to say we have problems too.' The men stayed quiet. I don't think we realize how quickly time moves because now those men's kids, their sons, have grown up only hearing the 'future is female,' they're used to hearing things like 'typical men' or 'typical straight white men.' Out of politeness, the liberal men have stayed quiet.

This has left this vacuum where very misogynist men have started to suggest to young boys who have only heard about the future being female that it's time to talk about boys. These men are suggesting you should be proud of your masculinity, but they are taking it further and saying that the thing that will make boys feel better is having power over women, which means regressing 50 years, 100 years, to those classic male-female stereotypes.

I very strongly suspect that power is not what will make young boys feel better. What boys need is empowerment because that is what feminism has given young women. And ultimately, that is what those young boys envy. That is what's making them angry. Women have learned to empower themselves, and there has not been the same movement for young men.

Girls and women feel immense pressure to be certain ways. You cover how boys and men feel pressure, too. One example is the expectation that all boys should love sports. Talk about those contrived expectations and how they're damaging and prevent boys and men from having intimacy.

After I'd written the book, Trevor Noah did this brilliant monologue saying how boys and young men, so much of their conversation with each other is about being horny and having sex with women. He said often when men say, 'I want to f&*K' or 'I'm really horny,' they're actually saying, ' I want to be held.' But the only way that boys can talk about that is through wanting to have sex because that is the only time you're going to have any kind of intimacy. There are statistics from sex workers who say they're constantly surprised by the number of male clients who will pay not because they want sex but because they want to sit, talk, and be held.

What has surprised you in writing this book?

I thought I'd write something very warm and friendly, a starter kit for men to start talking about these things. I was surprised that the word I used the most often in the book was heartbreaking. Men are paying to be hugged. Men cannot say to women or their male friends that they need to be vulnerable. They need to just hang out and talk about their anxieties and problems. They need to be hugged. Men need us to go and do something about it for them.

I've been doing a live tour in the UK, and I've had so many men come up to me to talk about the chapter about male friendships. They've said, 'I read about friendship being a verb, a doing word, and you have to schedule it, and I rang my friends to ask if we could just hang out and talk, and it felt really weird. It was almost like I was asking my friends on a date. I felt nervous because I'd just never done that before. I'm so unused to this.' Men of every age, in their twenties and in their seventies, were saying this. So again, it was heartbreaking. Men broke my heart in the writing of this book.

Regarding physical and mental health, men don't seek the help they need as readily as women. We've covered this in The Sunday Paper: men must open up and be proactive about their mental and physical health. What have you found?

In finding out why men often were reluctant to get help, I found that men put women and children first. Generally, I have heard that men leave it to the last minute. They are too stoic. They worry that it will impact their income. They think women and children should be on the waiting list ahead of them. And it's one of those things where there is no hierarchy of pain. A man doesn't hurt any less than a woman. If a woman has cancer and a man has cancer, it hurts equally. We all need equal help. Again, the female culture is that we will talk about these things more and prepare for these things, but it's not in the male culture.

You've built a career around writing for and about women, so this book surprised many. But you make the larger point that empowering men is about humanity and building a better world. How do you underscore this?

We're all brothers and sisters together. I come from a big family, and from an early age, I've had fairness inculcated in me. Women's lives have changed and progressed incredibly over four generations because we put in a lot of hard work. Women have found a way to exist that is a bit better than the way that men exist at the moment, that is more emotionally connected, and all we want to do is share it because if the men are okay and thriving, then the women will thrive too.

What people often misunderstand about feminism, sometimes women but most often men, is they think that women want to win. The whole point of feminism, the one-line description of feminism, is that women want equality with men—sexual, physical, economic, and emotional equality. And it's not equal if the women are going to the doctors and getting diagnosed, if the women have those support teams, if women aren't lonely, but men are. We all need to be equal. I feel like women have this amazing gift we can give men. It's like, 'Yes, we've spent a lot of time talking about our emotions; you can learn a couple of lessons from us!'

It's interesting to hear the presumption from many people that women have gone too far, and now it's time for men to become supreme again. No, no, no. It can only work if we're equal. It never works if you have a monoculture. If women were ruling the world, it would be equally as bad as men ruling the world. We need a proper 50-50 mix. That's why 50 percent of the population is male, and 50 percent of the population is female. Nature has designed it so that we're equal and should share everything equally.

What has been the reaction to the book?

There's been an emotional reaction. About a third of my readership is men. Men have read my books about women secretly like a manual, and they think now I understand my wife. Similarly, with this book, I've met lots of women who say, 'And now I understand my husband or my son.' But many of the men I've met have been very emotional. We've often had people crying in the audience when we're talking about loneliness. The way that economics works, many of the men I've met have had first families that have broken up because the men were so involved in their work. They felt that they caused so much heartbreak because of the way things are set up and the way that paternity leave works, they just couldn't be there. That's an unfair agenda. So the emotion has been, it's been a big one.

Also, there's been such hope. I never talk about a problem until I have a solution. I've heard many men who told me, 'I just went to the doctor' or 'I rang my friend, and I went to see him.' We often think if you're going to read a self-improvement book, there's got to be something huge., like you're going to move to the country, become self-sufficient, and meditate. Sometimes, it's as simple as: Go get a checkup. Ring your friends. Don't be embarrassed to talk to your kids about sex or watching pornography. Be aware that when you build up your daughter and tell her how girls are amazing, your son is listening, and you need to make sure you're talking about boys just as much.

Caitlin Moran is a journalist, columnist, and the bestselling author of numerous books including How to Be a Woman and the newly released What about Men? You can follow her on Twitter at twitter.com/caitlinmoran

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.