How Bestselling Author David Von Drehle's Unlikely Friendship with His 109-Year-Old Neighbor Taught Him the Secrets for a Happy, Useful Life

Like most fathers, David Von Drehle read to his four kids when they were growing up. Together, they devoured thousands of pages of Harry Potter and tore through Diar(ies) of a Wimpy Kid. They wiped away tears reading classics like The Red Badge of Courage, Where the Red Fern Grows, and Charlotte’s Web.

At some point, Von Drehle’s children learned he was a journalist—and they asked him to write a book for them. While he tried to write the kind of children’s novels he loved reading to his kids when they were little, his attempts failed.

That is, until this month, when The Book of Charlie was published and skyrocketed to the top of the New York Times bestseller list.

It’s not exactly the book Von Drehle’s kids requested. Instead, it’s a story of a 109-year-old man’s remarkable journey through life and the wisdom he imparted on everyone who knew him. Still, Von Drehle wrote this book as a gift to his children, which they’ve now read—and loved.

“I think they’ve forgiven me for never giving them a pirate ship adventure with a time travel machine,” says Von Drehle.

The Sunday Paper sat down with Von Drehle to learn more about his unlikely friendship with his centenarian neighbor and friend, the many lessons he learned from Charlie’s remarkable life experiences, and what he hopes all of us might take away from this book.

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID VON DREHLE

How did you get to know Charlie? What drew you to him?

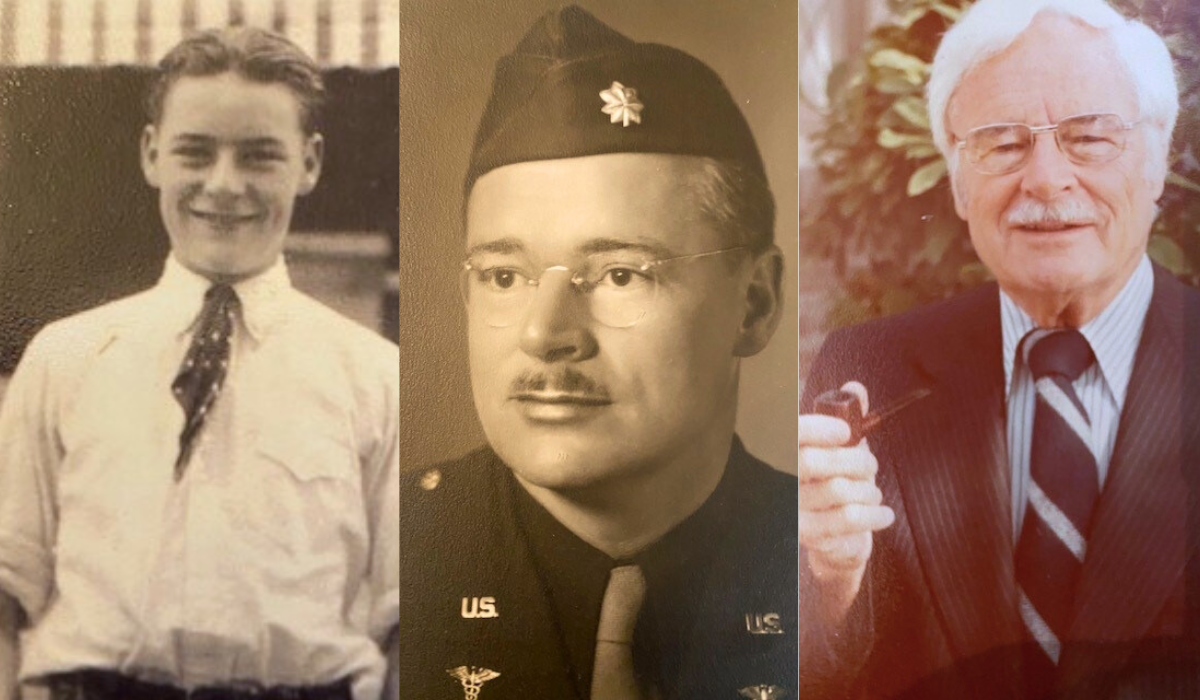

In the book, I describe the scene of our first meeting one Sunday morning soon after my family had moved from Washington, D.C. to Kansas City. Charlie was shirtless and washing his girlfriend's car after their Saturday night date had obviously developed into something that kept her there all night. He was 102 years old at the time.

There was a magnetism about Charlie. The world has changed in ways that have made it harder to meet our neighbors than it used to be. But in Charlie’s case, he was like a magnet drawing me across the street to get to know him.

And he was so easy to get to know. He was this very gentle, vigorous lifeforce. I think I would have wanted to get to know him even if he hadn't been 102 years old. When I found out he was this once-in-a-lifetime specimen, that certainly added to his mystique.

Over the years, you’d sit in his den and he'd tell you stories. You’re a journalist, so did you just start asking questions about his life—and your friendship grew from there?

Yes, that's exactly how it went. Charlie was curious about me; a lot of people in our neighborhood were curious after we moved. In Washington D.C., you can’t throw a baseball down the street without hitting a reporter or somebody working in journalism. Here in Kansas City, journalists are a little less thick on the ground.

But I was more curious about Charlie, and he quickly understood that his stories were more interesting than mine. Getting to know him was effortless; there was no work involved. He was he was an open book. He radiated confidence, but not in a boastful way. He was just very comfortable with who he was, what he was about, and what he stood for. And that made him very accessible.

I describe a scene in the book when I was in my front yard with my kids and Charlie came out to his driveway and waved for us to come over so he could show the kids around his yard and house. That’s just the way he was—always eager to make friends. I think it's a secret to happiness in old age. If you're lucky enough to live a long time, you have to keep making friends. Otherwise, you're going to lose all of them with time as you outlive them. Charlie had a genius for making friends.

One of the many lessons Charlie taught you is that America has always been a divided and politically intense country, but that people make choices of what they’re going to focus on. Tell me more about this…

Charlie had lived long enough to see so much. In the book, I describe a story of his cross-country automobile trip—this was before there were roads and highways—in a Model T with a couple of his friends. It was the early 1920s, and when he was driving across Kansas and Colorado on his way to Los Angeles, he was driving through states where the state government was openly dominated by the Ku Klux Klan.

The 1920s were a time of tremendous division in American politics—bitter, bitter division. There were race riots, and lynchings, and open white supremacy. When Charlie was born in 1905, he was closer to the Civil War than children born today are to the war in Vietnam. That means the older men that he met as a young boy were men who had fought and died in a war of division.

This idea that America had never been divided before? Charlie understood that wasn't true. We've always been a divided nation; we've always been a passionate nation. But we've always found our way through it. And we've put one foot in front of the other because ultimately, we're a nation of Charlies. We're a nation of people who have an ability to argue, to disagree, but also to appreciate things that we share and value that are not political. I think Charlie's wisdom, which maybe we've forgotten a little bit right now, is that not everything is politics. There's a lot of other important stuff that happens in our lives.

Life isn’t about politics. It’s about relationships. It's about family. It's about work. It’s about adding value to our communities.

At the end of his life, Charlie wrote down what he’d learned in his 109 years—short little instructions for life. What were your initial thoughts when you read these?

As Charlie reached his great age, everybody would ask him two questions:

“What's the secret of long life?” (He'd say there is no secret; it's all luck.)

“What’s your philosophy of life?” (He’d say he didn't really have one, and that his mother always just told him do the right thing.)

But after he died, his family found a piece of paper among his things, and it was obvious he had taken those questions to heart. He filled the front and back of the page with two- and three-word commands, almost like computer operating code for a happy, useful life. These were things like:

Make some mistakes.

Learn from those mistakes.

Listen to the rain.

Enjoy wonder.

Observe miracles.

Make miracles happen.

Each one of these almost sounds like a greeting card or social media meme, but when you add them up, they get to something really profound about what remains after everything else has fallen away. They seem trite until you realize that they're familiar because they're true.

Your kids always asked you to write a children’s book, and you say The Book of Charlie is that book. What do you want your kids—and all of us—to learn from Charlie and the stories you share about him in this book?

After Charlie was gone, I realized this was the book my kids needed. They are going to live in a century of enormous change, and we don't know what that change is going to look like exactly. Who else went through that amount of change? The people who were born at the very end of the agrarian age, back when most Americans lived on farms and when almost no one had an automobile. This was before radio, before TV, before penicillin—and then these people managed to live all the way into the age of the iPhone and the International Space Station. That was Charlie. He had done that. The amount of upheaval, change, revolution, disruption and strain he lived through was astonishing. I realized that's the story my kids needed to hear. He was the Pathfinder they could draw lessons from, more than myself.

I hope people will read The Book of Charlie and take a new look at the world around us and the situation we're in and realize the world has always been divided—it's been broken. We're human beings. We've always been making mistakes. We'll make more in the future. Yet despite all that, this can be a rich, beautiful, rewarding life. And a big part of that is how we choose to frame our own stories.

Question from the editor: How would you answer the questions Charlie was often asked as he got older: What’s the secret to a long life? What’s your philosophy of life?

David Von Drehle is a deputy opinion editor for The Washington Post and writes a weekly column. He was previously an editor-at-large for Time Magazine, and is the author of four books, including “Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America’s Most Perilous Year” and “Triangle: The Fire That Changed America.”

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.