In Our Ever-Divided World, Revered Author Pico Iyer Guides Us Toward Peace and Beauty

For more than 50 years, Pico Iyer has traveled the globe, submersing himself in cultures and landscapes of vast differences while always finding the truths of humanity that transcend borders, politics, and location. The journalist's insights are immeasurable and filled with wisdom, as are the 15 books he's written (which have been translated into 23 languages and range in subject from inner paradise to the Dalai Lama to Islamic mysticism). His work mirrors his approach to living: with eyes and heart wide open.

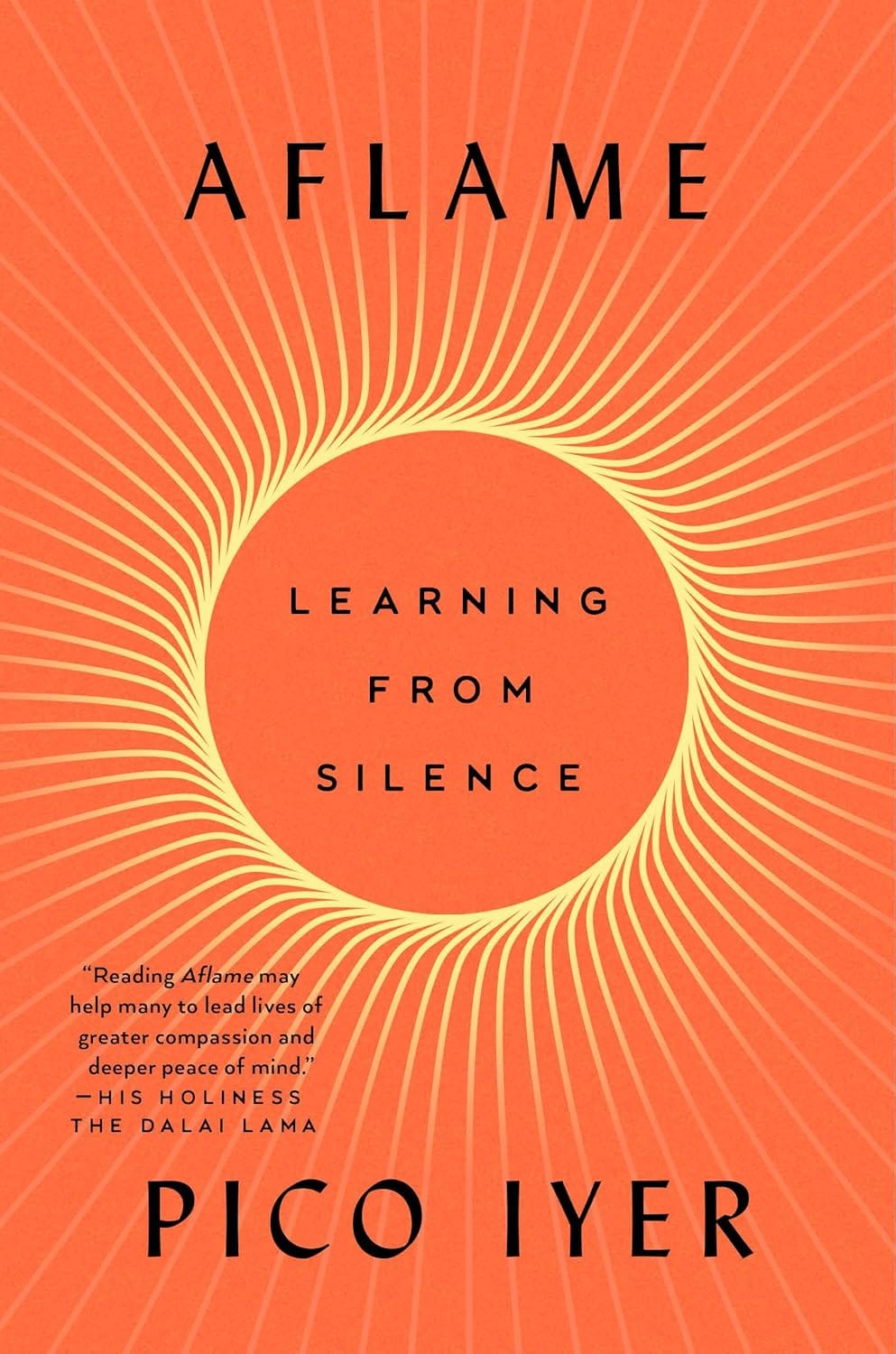

We wanted to speak to Iyer this week to understand how to find peace within ourselves and each other when the world feels unstable. It's a fitting topic for the author, given that he anchored his last book on the concept of finding inner paradise and his forthcoming book, Aflame, on what he learned from seeking silence during 30 years of visiting a monastery. Iyer graciously called us from his home in Japan and offered his perspective on seeing things “on a much wider canvas,” as he says, and always finding the beauty.

A CONVERSATION WITH PICO IYER

We last spoke in early 2023, and we were discussing your last book, The Half Known Life. You told us a big reason for writing that book was the pandemic and how so many of us were anxious and seeking to address the question of how to find calm in the face of adversity. Now, here we are in another situation of adversity where so many of us feel anxious again and face disagreement with others. Considering the vast stories you've covered about how to find inner peace, what are you thinking about prominently right now?

As I hear you say that, I'm reminded that during the pandemic, pretty much every human on the planet was in the same situation and sharing the same anxiety and unsettledness. At some level, we had a choice whether we would concentrate on everything we shared, which was a huge amount emotionally, or whether we would concentrate on what we didn't share, which had to do with our political, religious, or ideological differences. I always feel, especially in this global age, our main challenge and the question for every one of us is: How do we live and work with people with whom we don't agree? Whatever and whoever you voted for, millions of Americans around you didn't share that assumption. So, the real question is not how do we get on with everyone we agree with, but how do we get on with the many with whom we disagree?

In the book that I'm about to bring out, one question I ask was the one you just asked: How do we remain calm amid the flames—whether they're literal flames, metaphorical, or emotional? And secondly, how do we look past our borders? I've been lucky to spend 50 years talking and traveling with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. One thing that's always moved me about him is that he wakes up every day and begins by praying for the Chinese brothers and sisters, as he calls them. In other words, the government that almost wiped out his own country. And I'm guessing the Chinese leaders don't wake up praying for the Dalai Lama. But I feel that's the victory that he will always have over them, especially in the long run.

So much of your work has focused on the truth that many things in life are in collision. In your forthcoming book, you share your experience of making more than 100 visits to a monastery where you embraced silence. And while you were doing so over the years, loud things were happening in your life, including death, loss, and your daughter falling ill. How has seeking the solace of silence helped you participate in a world that is always in collision and chaotic?

That has always been an essential question, certainly in my life. At the beginning of the book, I quote a Zen teacher here in Japan who says that it's easy to sit still in the meditation hall, but how do you sit still in the middle of the tumult of the world? One thing I gained from driving regularly into silence is the sense that everything is impermanent. Grief and anxiety and fear don't last forever. Even joy, contentment, and peace don't last forever. When I go there, it's partly a matter of seeing things on a much larger canvas. Every time I drive up to the monastery in Big Sur, as usual, my head is full of chatter, and I'm arguing with myself and somebody I met last week. I'm worried about my family and sweating over my deadlines. And as soon as I step into this silence, which is not just an absence of noise but a positive presence, that all falls away. I am brought to my senses, and I'm taken out of my head, which is where all the fear and anxiety exist and brought into something much wider. I'm reminded I'm not the center of the world, and there are so many things more vast than me or my concerns.

In the book, I describe how my father died suddenly. As an only child, I was caring for my mother a lot at the time. She was, of course, distraught as she had been next to him for 40 years. The only way I could find to respond to that very busy time was one day, when someone was caring for my mother, driving three and a half hours up to the hermitage just to sit in silence. I went to sit on the bench above the Pacific Ocean. Hearing the bells curling in the distance and remembering everything that didn't change in this life and world of constant change, I just sat there for two hours in this pure landscape. Then I drove three and a half hours back. And somehow, something in me was cured.

When the Dalai Lama faces questions about what to do with our grief and loss, he always uses the phrase, wider perspective—whether it's wider in time or space. In the United States, I know so many of my friends over the last many years have been very worried about the state of the nation and, therefore, the state of the world. Then I go to China, India, and many other much larger countries, and people have such a sense of possibility. So, I always want to avoid having too narrow a perspective, both in terms of just being caught up in this moment and also just being caught up in my little life and failing to see all the improvements in the world and all the possibility.

It is quite profound how quickly we can lose perspective and a sense of all the possibilities and how easily we can take things for granted.

This is not to do with the recent election, but just generally, I keep shaking myself to think of how the world has moved so much forward in the course of my lifetime in ways I never could have imagined. I don't want myself to forget all that in the midst of the turbulence of any particular moment. Here, you and I are speaking so easily across the ocean. I never imagined that one day I could just sit in my apartment and, on a quiet morning, see and talk to somebody on the other side of the world. Generally speaking, it's a good exercise to remind ourselves of what we take for granted. As somebody who's worked in the mainstream media for more than 40 years, I worry that the media concentrates on what happened a minute ago and what's tumultuous when there's so much advancing and evolving that doesn't get featured in our headlines.

It seems we often forget that these stillness and peace belong and are available to all of us. Right now, when we're feeling like we're spinning, what direction would you point us in to find some peace and beauty, as well as a release from this chatter and anxiety?

I would say, if possible, take a walk. Walk along the beach, if you can. Hike into the mountains. Give yourself a chance to open some space in your mind so that something other than your thoughts can come into you. What's so interesting is the word that the monks always use for what we find in this place: recollection. It's not a realization or sudden discovery. It's recollection—remembering something some part of us knew but was misplaced along the way. It's recollection in the sense of collecting everything as a whole rather than being scattered as we so often are. I believe that is something, as you say, that is available to us to some degree at any point. I feel that I have a social, chattering self and a silent self. The social self is happy to engage in debates and arguments with anyone, but the silent self is much deeper than that; it is beneath my words, ideas, and ideologies. I think that's what brings us together. The external world is so deafening now that I think the internal truth gets drowned. So, at any point in the day, if we could recover that inner, quieter, deeper self, which is the source of all our strength and clarity, I believe it's in all of us. But we sometimes get so caught up in the exhilaration of following the news and racing from place to place that we lose it, and then we wonder why we're feeling so lost.

One of the things that I love about this monastery I go to is that it is a Catholic monastery, and I'm not a Christian. The Catholic monks who don't share my faith open their doors and their hearts absolutely to me and everyone else who doesn't share their fundamental faith but shares their humanity. It's a reminder of how this is all about finding our common humanity. If you're walking down the street tomorrow and somebody falls, you reach down to help her. You don't ask her if she is a Democrat or Republican or if she is Muslim or Christian. You see that she's a human. That is the best part of us, but that is what tends to get lost. Our head starts cutting the world into categories and saying we don't like this person or don't agree with that person. Whenever I get out of my head, I am in a better place. So, wherever you happen to be living, you can do something, whether listening to a piece of music, going for a walk, playing tennis, cooking a meal. It may be practicing yoga or meditating. There are ways that we can get out of our divided selves and into our much more expansive and welcoming selves.

Pico Iyer is the author of 15 books, and has been a constant contributor for more than 30 years to Time, The New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. His next book, Aflame: Learning from Silence, will be released in January 2025. Learn more at www.picoiyerjourneys.com.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.